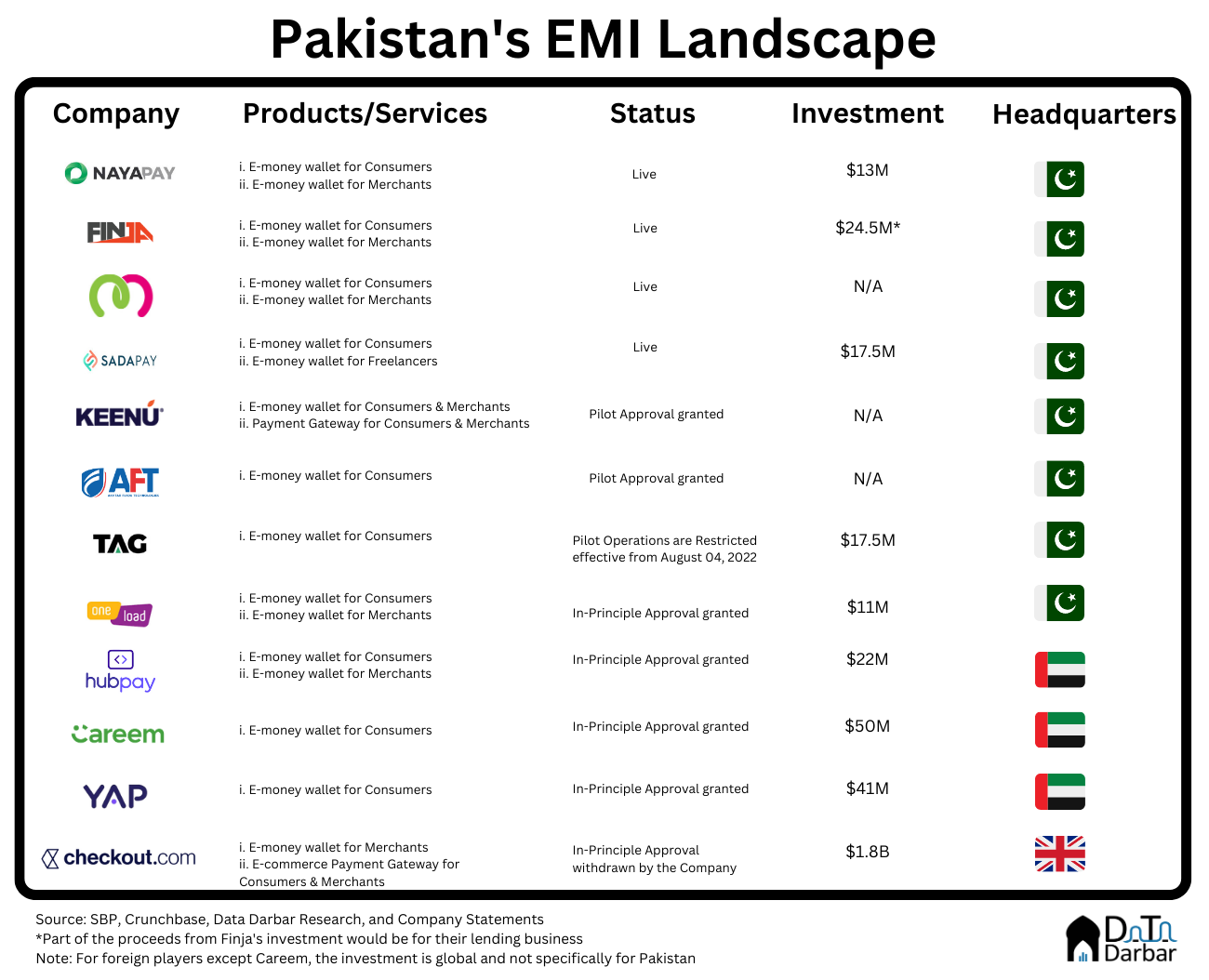

A couple of days back, someone forwarded me a screenshot showing that Checkout.com, a London-headquartered fintech with ~$1.8B in funding, has withdrawn its application for the Electronic Money Institution (EMI). The company had received in-principle approval for the EMI license from the State Bank of Pakistan on Aug 12, 2022, but was officially out of the licensing race by Apr 5, 2023. No communication or reasoning has been given for the move, but an employee said it was due to the deteriorating macroeconomic situation.

In a week, it became the second foreign player to exit Pakistan, the other being Egypt’s Trella. The way things are going, this could end up spelling trouble for the country much like the 2022 scaledown in the tech ecosystem. However, Checkout’s reasons may not be entirely driven by macroeconomy, as bad as it currently is. It could possibly be related to EMIs, specifically their mandate and timelines, which are painfully long.

Read: How will EMIs make money?

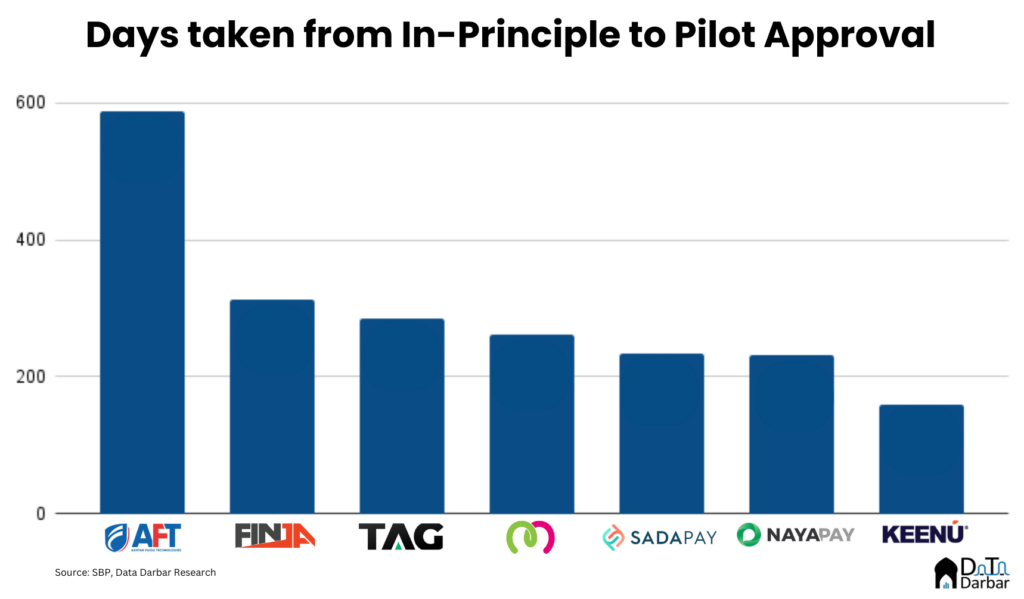

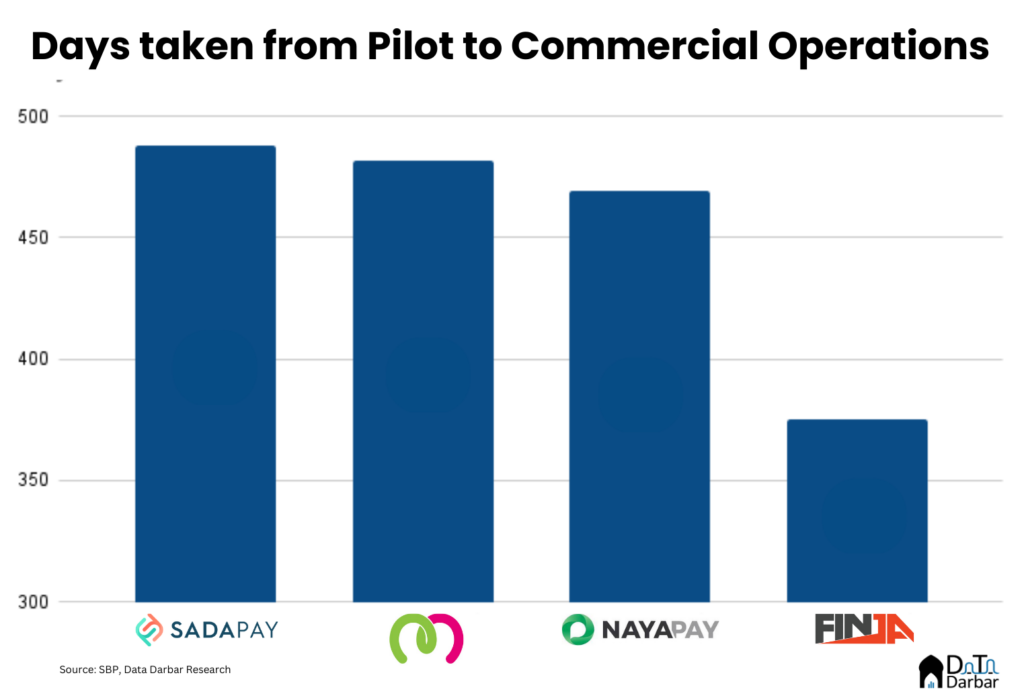

So I looked at how long it took EMIs to get to their major regulatory milestones. The average number of days taken by fintechs to graduate from in-principle to pilot approval was 295. Or almost 10 months. To receive the go-ahead for commercial operations from there, the wait was longer: 454 days, or around 15 months. This doesn’t factor in the time to first get the in-principle approval, which too can take at least a few months. In one case I am familiar with, even years.

Needless to say, the long timelines have explicit and implicit costs. For starters, you do roughly three years of operations without really making any revenue. To make matters worse, it’s not possible to stay lean either, because of, you know, the regulation itself which has tonnes of requirements like hiring people in risk, compliance, and dispute resolution. Basically, you need to set up proper departments very early on and get expensive resources to manage them. Add to it the infrastructure, capital requirements, and more.

These are just the explicit components. A bigger problem could possibly be the implicit costs. For example, employee retention can be a major challenge for any pre-operations company. The resources, especially ambitious early career professionals, inevitably get bored of waiting and move on to, well, organizations that are actually in the market. Or they rot, which is even costlier.

Perhaps this is why the PSO/PSP Rules of 2014 failed so terribly. Almost nine years later, only five of the 12 entities that initiated the process are commercially live. Two of them are 1LINK and NIFT — which have existed since the 1990s. Another five abandoned their plans after getting in-principle approvals more than half a decade ago. Foree, currently under pilot, seems to have given up too as both its founders have long departed the company.

Of course, it’s possible that the fintechs abandoned their PSO/PSP licenses for reasons other than the timelines. Maybe the use case didn’t make sense anymore. Or that the introduction of EMI Regulations in 2019 made the whole thing far less appealing. In either case, it’s hard to argue that wait times running into years don’t discourage businesses and sponsors.

The same goes for the EMIs where not every delay is on part of the regulator. There are cases of companies unable to meet their minimum capital requirements or have shortcomings in compliance. And given the public’s deposits are at stake, it’s understandable why the SBP would want to be cautious. Especially now, after the whole TAG incident.

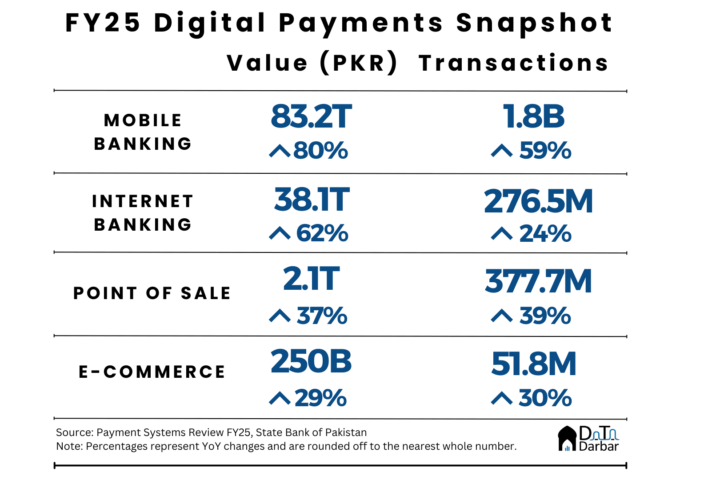

However, there’s an undeniable need to speed up the process. Otherwise, you can keep churning out a new licensing regime every few years, and create some hype before it all fizzles out. All those financial inclusion goals be damned. Plus how do we measure them anyway? For instance, the SBP recently disclosed a few figures related to the EMIs, including total accounts registered, e-commerce merchants onboarded, and so on.

But are those really the right metrics? If banking the unbanked is the goal, then maybe we need to go a little deeper. Instead of giving a standalone number on account openings, we should at least be looking at how many of those were accessing formal financial services for the first time? Or what share was from outside Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad? And a lot more.

You could argue how it’s still too early to get into these details for EMIs, as they have been operational for just over a year or so. But that’d be ignoring a historically rich pattern of masking the incompetence of the financial services sector by both the industry and the regulator.