When the International Monetary Fund (IMF) raises concerns about a particular sector in Pakistan, it demands attention. While sectors like energy and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) often hog the limelight, microfinance has lately started coming under scrutiny. Both the IMF and the World Bank have voiced apprehensions about the vulnerabilities plaguing microfinance banks in the country, pointing to potential threats these institutions might pose to the overall banking system if left unchecked. The sector’s viability has long been a concern and only amplified post-2022 floods.

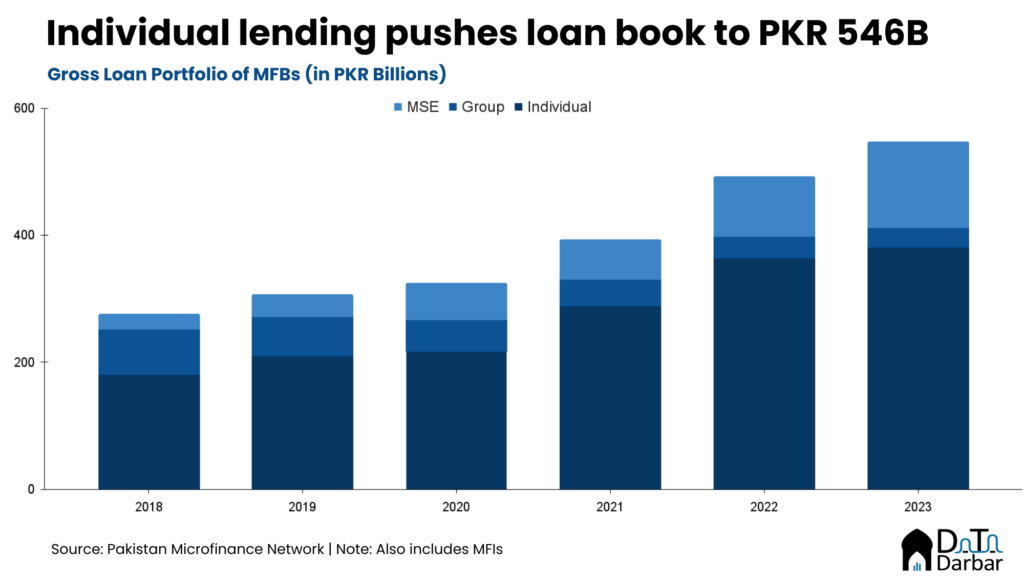

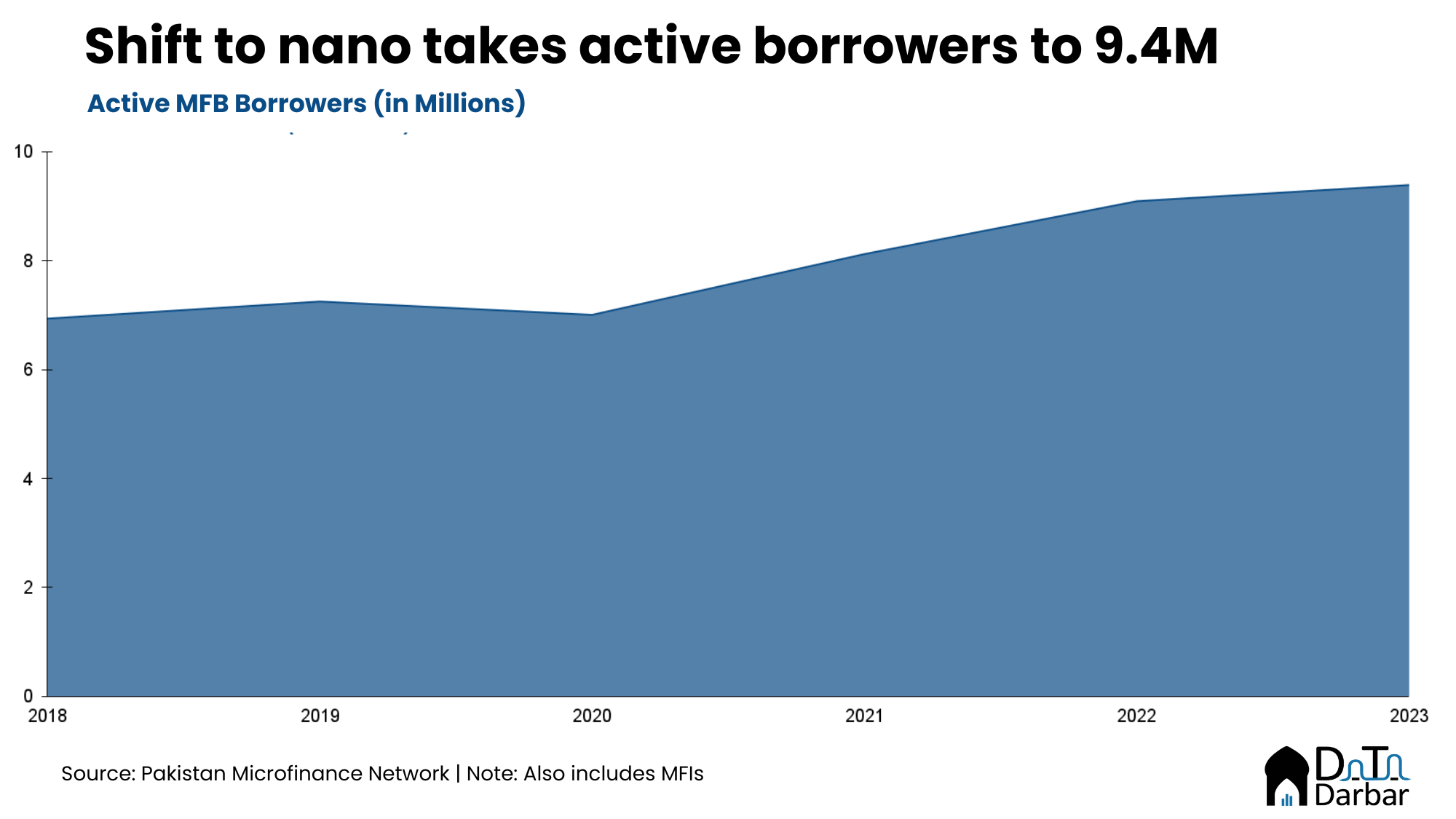

Even the sectoral body, Pakistan Microfinance Network, halted new data releases for almost a year. But last month, it published the flagship Microwatch for the latter three quarters of 2023. On the surface, everything looks good: the gross loan portfolio of both banks and institutions reached PKR 546 billion by December 2023, an increase of 11.2% compared to the same period last year and 3.1% over the preceding quarter. Similarly, the number of active borrowers peaked at 9.4 million, driven by continuous growth in individual lending.

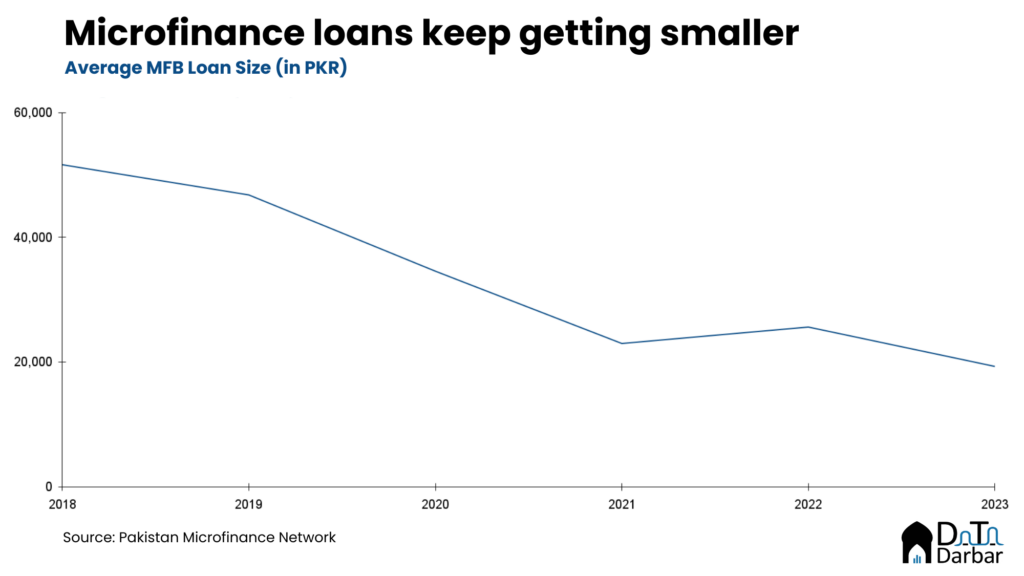

This growth is part of the industry’s broader shift towards nano finance, led by telco-backed players like JazzCash and Easypaisa since 2021. The average loan size fell further to PKR 14,493 in Q4 2023, compared to PKR 46,000 between 2016 and 2020 across the three categories (group, individual, and enterprise). However, these numbers don’t tell enough about the sector’s health.

Deposit mobilization picks up momentum

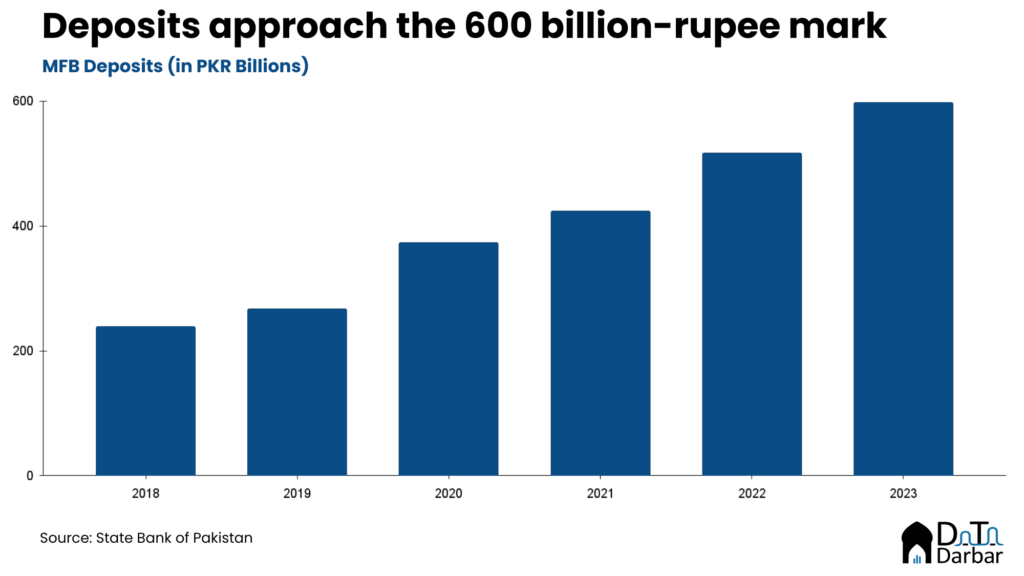

Microfinance banks have seen remarkable growth in their deposit base, both in value and number of customers, with the former reaching PKR 596B as of December 2023. This can be attributed to the high interest rate environment, which has made it more attractive for people to put their money in the formal banking system.

However, its composition can vary significantly. For instance, UBank and HBL Microfinance have deposit bases dominated by large tickets from financial institutions. In contrast, NRSP and Khushali Bank have focused on the retail market, increasing retail funds through strategic outreach and customer-centric initiatives.

Credit risk conundrum prompts strategy shift for major banks

Major industry players are struggling with credit risk management, prompting a lending strategy overhaul. Data shows a decrease in average ticket size, driven by JazzCash and Easypaisa and their sheer volumes. On the other hand, brick-and-mortar MFBs are looking to consolidate and shift towards higher-ticket loans backed by collateral, with housing finance and property/agriculture passbook-backed lending becoming prominent. HBLMF’s housing finance portfolio grew from 18% to 34% of its outstanding loans in 2023.

The MFB industry reported Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) at 9.5% in 2023, with declining asset quality due to increased provisioning for bad loans under IFRS-9. Concerns about the recoverability of deferred and restructured portfolios post-2022 floods further impact asset quality.

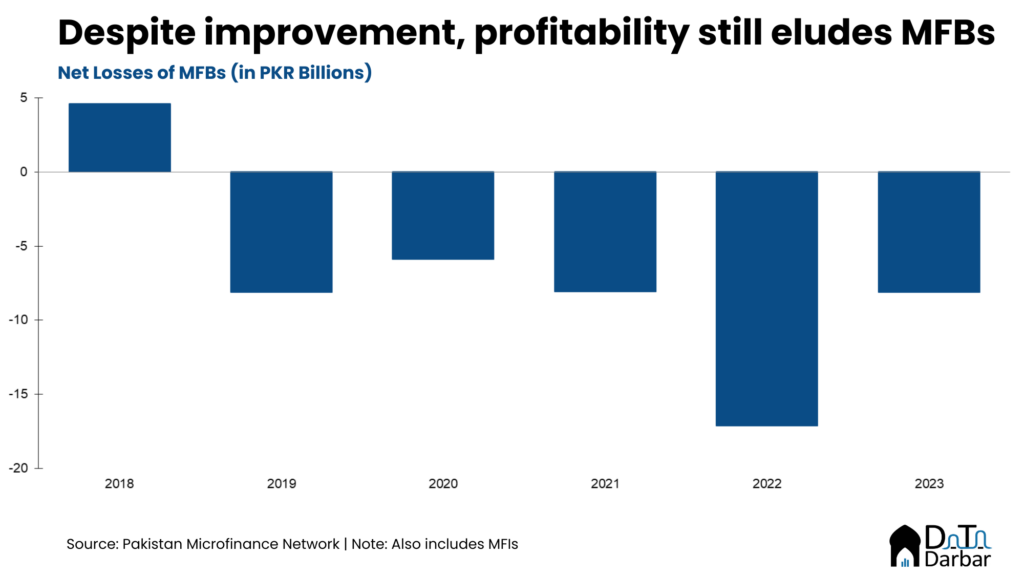

As sector fundamentals worsen, losses intensify

Consequent to the high credit risk materializing alongside the rising cost of funds, MFBs incurred a loss after tax of PKR 8.1B in 2023, making it the fifth straight year of negative net income. During the last 20 quarters, there has been only one period where MFBs didn’t post a loss and that too was a solitary profit of PKR 101M.

This is despite the fact that Telenor Microfinance Bank’s bottom line finally turned black in 2023 with a profit after tax of PKR 502M. In the preceding five years, it had played a major role in dragging down the sector’s bottom line and incurred a cumulative loss of PKR 47.4B. But others seem to have happily picked the tab instead.

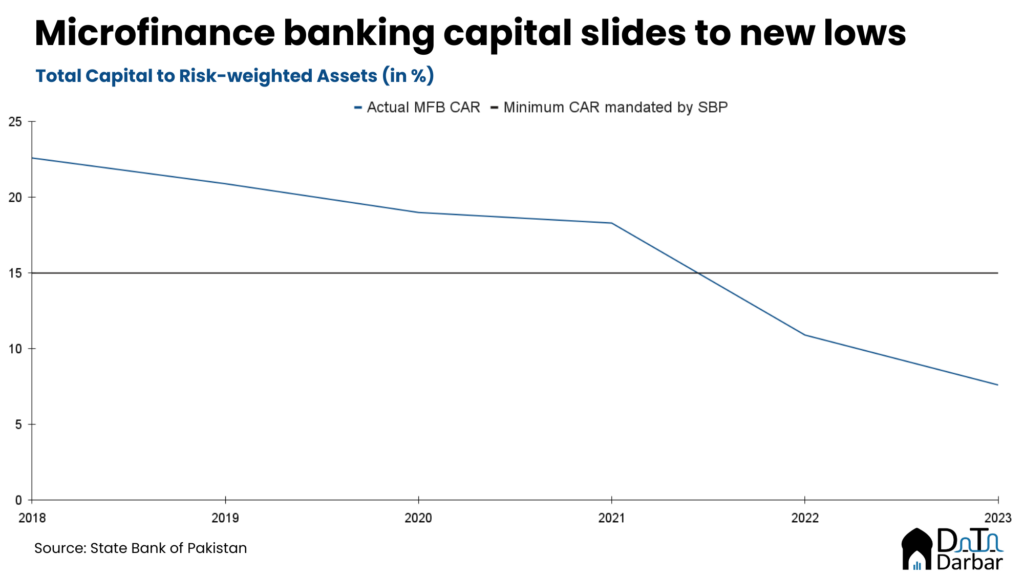

Capitalization rot spreads further

Mounting losses in the microfinance sector have led to deteriorating capitalization levels for MFBs. The State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) mandates a minimum capital adequacy ratio (CAR) of 15%, but since Q2’22, the sector has struggled to meet this requirement. The CAR fell to 7.6% at the end of 2023 and further to 6% by Q1’24. Key players like Khushali Bank, UBank, and NRSP Bank are now affected by the liquidity crisis.

NRSP Bank reported a capital shortfall of PKR 6.5B and a CAR of -6.02% in December 2023. Khushali Bank’s equity base dropped to negative PKR 4.4B, with a CAR of -5.7%. To address the crisis, these institutions are taking measures such as capital calls to sponsors, converting preference shares/debt to equity, and securing more subordinated debt.

There is nothing wrong with Microfinance fundamentals. Unlike Commercial Banks, which are hell bent on financing always-in-deficit Government of Pakistan, Microfinance Banks lend money to real economy of the country i.e. agriculture, live stock, small businesses. Of course when economy go south, loans go bad. What commercial banks are doing is fundamentally wrong, not microfinance Banks. What is fundamentally wrong is the banking regulator on “mute” on commercial bank’s unlimited investment in PIBs and TBs.