As a country, Pakistan kinda sucks at storytelling. Geopolitical events post-2000 surely made things difficult but even besides that, we never did a particularly good job. Sometimes it’s just a lack of effort due to our failure to effectively highlight progress. At worst, this means squandering away opportunities and at best, loathing in self pity. The state of our financial inclusion is one such example.

For years, we have heard how the penetration of formal financial institutions remains abysmally low. While this was certainly true at some point, things have changed lately. Between FY17 and FY24, more than 141 million accounts — scheduled + branchless accounts — were opened, reaching 211M. That’s almost two-thirds of our adult population. Is there room for more growth and better services? Sure. But is Pakistan still a basket case of financial inclusion? Not by a long shot.

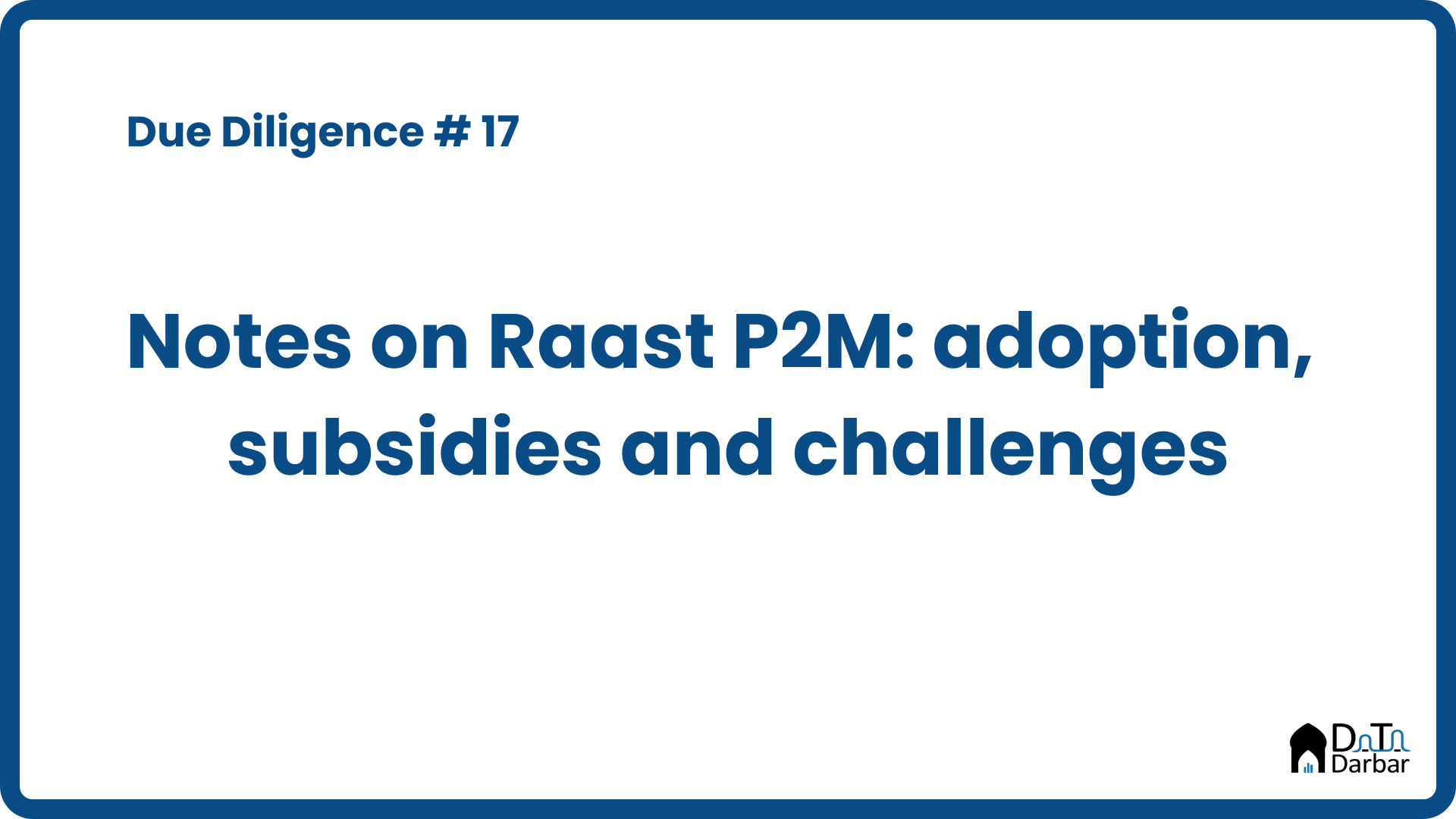

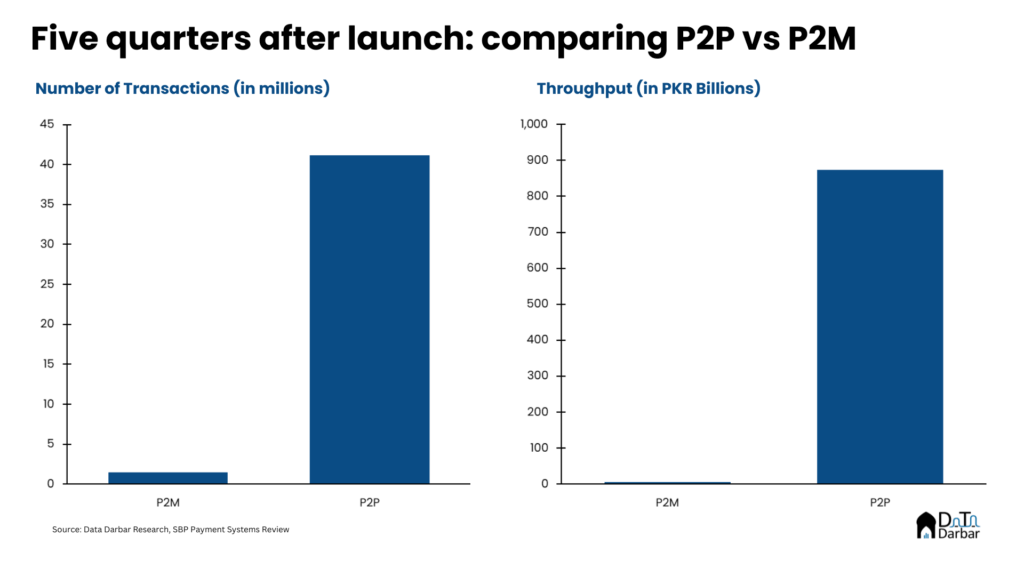

Much of this came on the back of digital wallets, which have become a major mode of conducting transactions. In the past, most of the focus had been on P2P i.e. peer-to-peer transfers but lately, the regulator has been aggressively pushing Raast’s person-to-merchant (P2M) module. While it may be too early still, the results so far aren’t promising.

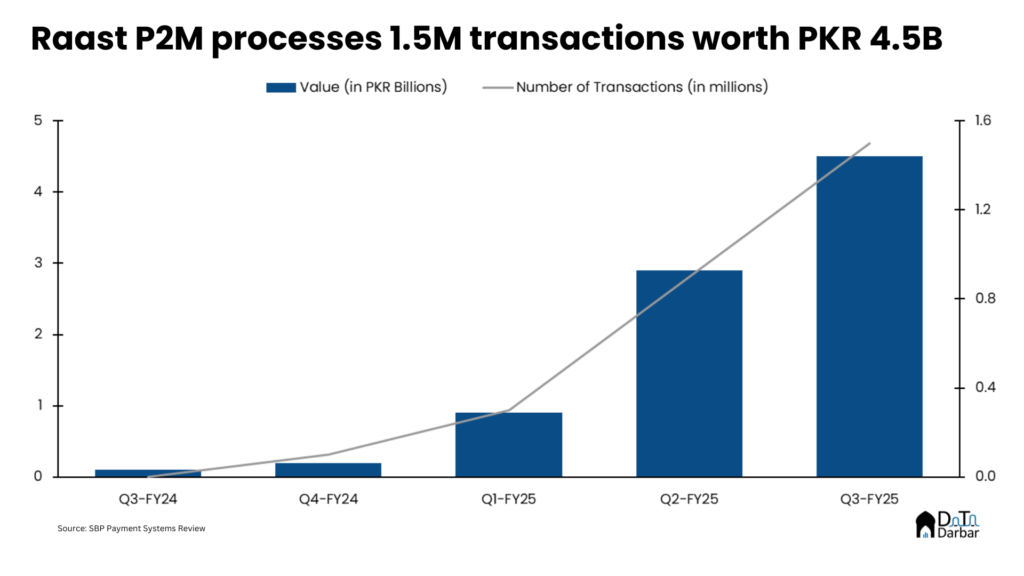

According to the latest Payment Systems Review, P2M processed only 1.5 million transactions worth PKR 4.5 billion between January and March. To put the numbers in context, the average DAILY volume through the P2P module was 4.1M during the same period. In other words, there were more transfers in a DAY via P2P rails than P2M in the entire quarter. Throughput-wise too, it was the same story.

So why has the uptake been unimpressive? There could be countless reasons, with the usual ones thrown around being:

- financial institutions not doing enough acquiring efforts to expand the merchant network

- retailers shying away from digital because of

- tax; or

- cost

Though each explanation has a degree of truth, the conversation on digitalization misses the mark for it assumes that only P2M falls within the ambit. As we have seen, that is not true. Take an InDrive, go to Zainab Market, stop by at a roadside dhaba for chai and the chances are that you won’t have to use any cash. All those merchants most likely will accept online fund transfers — whether through a bank or JazzCash/EasyPaisa. So the payment channel is definitely digital, just that the underlying rails are P2P instead of P2M. Does that really matter? After all, both the parties i.e. the buyer and the seller are happy.

P2P vs P2M: two facets of digital payments

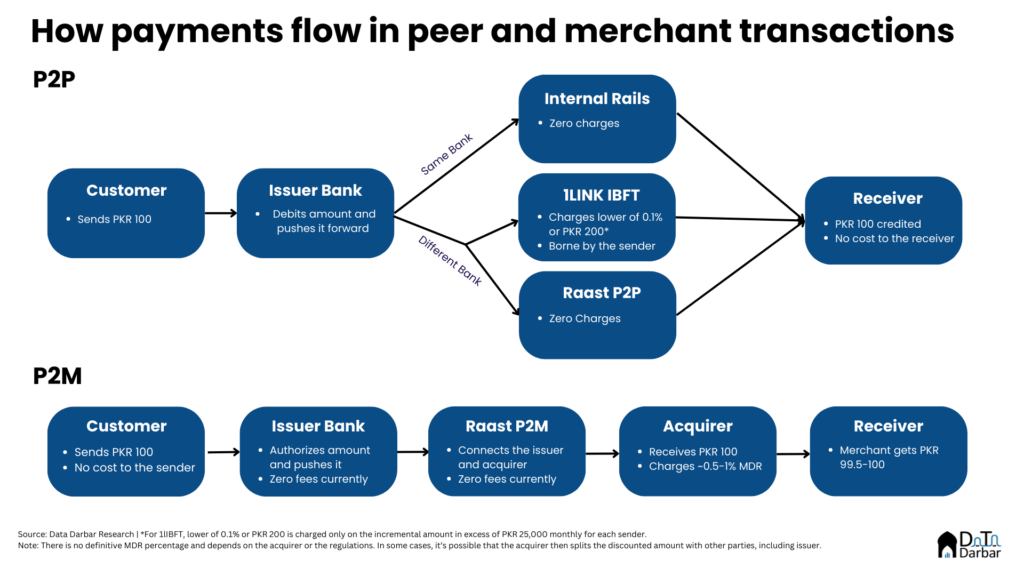

Technically, yes. Though both digital, there are some broad differences such as design or dispute resolution mechanisms. Most importantly, who bears the cost of the transaction: in P2P, it’s typically the sender who pays the charges. On the other hand, the merchant absorbs the fees, i.e. MDR, in P2M.

When both parties are already comfortable with transfers, paid for by customers, why would the merchant willingly share the burden? Secondly, commercial transactions — be they through card or account — have no rupee value cap on the MDR. Put simply, if you buy a meal for PKR 1,000, the merchant will get PKR 980, leaving the remaining to the many service providers in the value chain from acquirer to issuer and everyone in between. For many, including some retailers, that’s a fair price for the convenience.

Now suppose you are buying a brand new flagship mobile that costs PKR 500,000 and want to pay via card. In this case, the shop will receive PKR 490,000 and be discounted by PKR 10,000. That may no longer be worth the additional convenience. So for higher value items, the pricing structure may not be particularly attractive to the merchant. This is why many e-commerce stores charge customers additional 2-3% if they pay via card, thus passing on the MDR.

Perhaps not ideal, but there’s a reason behind such a pricing structure. Payment providers, like any business, make the largest chunk of their revenue from a small set of high value customers, who basically enable them to offer the same services to a broader audience, often at a lower margin. Put another way, your biggest clients sort of subsidize the remaining majority. Anyway, these are just some of the cost-related reasons as to why P2M is less attractive for merchants and if you want people to transition to something new, there should be some incentives.

For the longest time, those incentives were missing. While the regulator certainly wanted to expand the P2M network, banks had a good thing going on with P2P and didn’t seem too interested in upping the acquiring efforts. Probably except for JazzCash, which accounts for the majority of the 770K Raast-enabled merchants active on QR. It required heavy investments and an uncertain return, at least in the medium term. Unlike India or Egypt, there were hardly any VC inflows so the fintechs couldn’t aggressively subsidize demand or supply.

How India scaled P2M

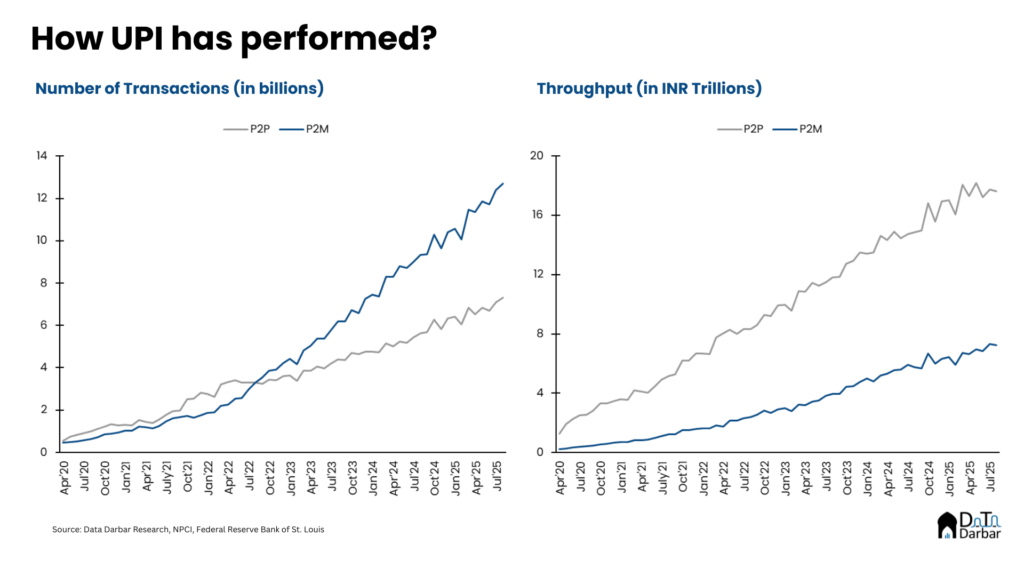

Which brings us to India’s unified payments interface, because no conversation on national payments stack is complete without its mention. And rightfully so: just in August this year, UPI processed 20 billion transactions. Without drawing comparisons, it is important to understand what enabled such massive scale across the border? Demonetization, coupled with increasing mobile phone and broadband adoption thanks to subsidised pricing by players like Jio, surely helped but one critical driver was the removal of merchant discount rates. As a result, neither the small retailers nor the end customers had to bear any costs for transacting via UPI.

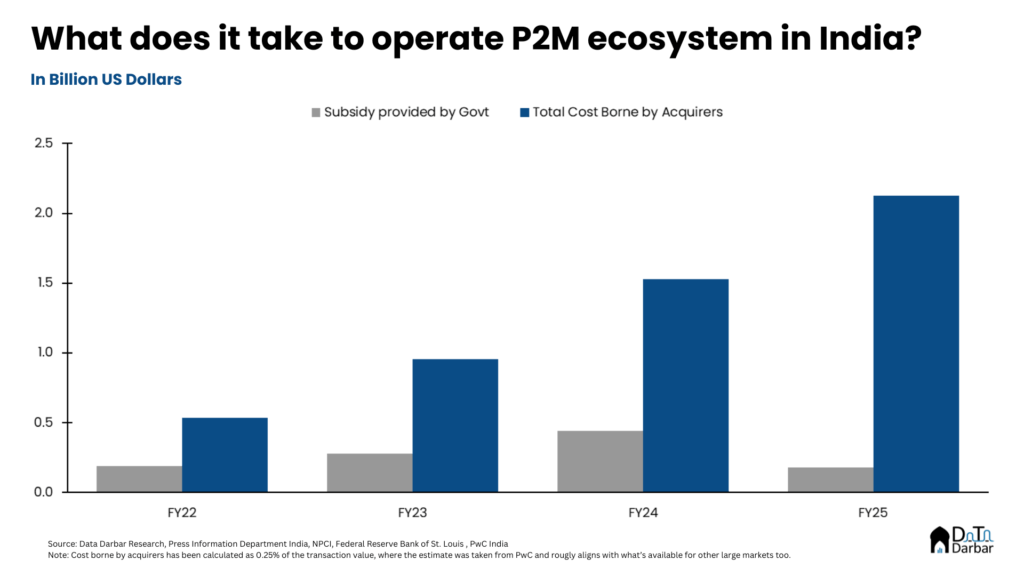

However, no fees =/= no costs: building and maintaining such a massive infrastructure is far from free. Payment providers incur heavy expenses in deploying field forces to acquire merchants and running the systems that facilitate the seamless payments, now without earning anything on it. According to PwC, the cost of processing a P2M transaction is on average 0.25% of the transaction volume. For smaller markets with lower economies of scale, it may be higher. Given the FY25 volumes in India, it translates into opex of $2.1B on part of acquirers. It’s a steep cost — just under 5% of the Indian banking’s net profits worth $43.9B.

In contrast, the Indian government’s subsidies have only covered a fraction of the cost. Over the last four fiscal years, only 21% of what the acquirers bore was subsidised by the Union, with the figure slashing to just 8.4% in FY25.

Finance ministry and the P2M incentive structure

The Pakistani government is finally stepping in to foot the bill and recently approved subsidies to this end. As per media reports, PKR 3.5B has been earmarked to support the usage of Raast P2M, for which it will reportedly pay the lower of 0.5% or PKR 200 (some reports suggest PKR 100). Let’s put the numbers in context: based on the current average ticket size of PKR 3,000, this translates into MDR support of PKR 15, enough to cover volumes of almost 233M.

But the more important question is: how long will it take to get there? In the case of the P2P module, the figure (on an annualized basis) was hit right after the seventh quarter of launch. If things go at the same pace, the MDR subsidy should run out in the very first year of its approval. However, comparing the two isn’t right: the former already had a high organic growth trajectory while the latter needs to be built from ground-up, against existing systemic frictions.

Beyond subsidies, what has always baffled me is why the regulator hasn’t yet tried a similar pricing structure as interbank fund transfers. I mean it works pretty well: banks find it lucrative enough, merchants are accepting, and customers seem to have no qualms about the cost either. All while growing fairly aggressively (until Raast replaced it, of course, as the preferred rails). Of course there are going to be differences between any P2P and P2M models, including the quantum and split between different parties.

Documentation, not costs

In any case, this is a welcome move. But as noted earlier, cost is only one of the barriers: retailers avoiding documentation is another factor. The problem there is that tax comes under the mandate of provincial and federal revenue authorities, not the State Bank, creating a distributed responsibility. This has been the missing link for a while now, amid half-hearted measures to formalize retail sector and backing out at the first sign of pressure.

Thankfully, the government seems to be getting serious. As far as announcements go, the Finance Division mandated all shops in the country to 1) display a QR code and 2) as a rule, accept digital payments if a customer asks for it. The deadline for this was Aug 31 so it’s safe to assume things haven’t yet moved at the desired pace. Simultaneously, other regulators are stepping in to do their bit. For example, the Oil & Gas Regulatory Authority directed all marketing companies, gas utilities, CNG stations, LPG and LNG operators, refineries and lubricant marketers to introduce and prominently display digital payment options, including Raast QR, at their outlets. Similarly, the SBP on behalf of PM has given hard targets to all its regulated entities to activate 2M merchants for digital payments by the end of June 2026.

Everyone is an acquirer now

However, just like promises by teens in love, these targets don’t hold much value. We have seen repeatedly how such goals are usually never realized, whether for SME financing, women financial inclusion etc. You could pin it to countless reasons: from a lack of will, misaligned incentive structures or something else entirely. Ultimately, it’s a capacity issue as financial institutions don’t have the technology or HR (think field forces, product people etc).

With P2M, we are potentially looking at a similar problem because most financial institutions have little merchant acquiring expertise. Until recently, only nine banks were doing point of sale, half of whom were in closed-loop. And that industry, despite seeing healthy growth in the last two years, remains at 179,000 terminals as of March. In comparison, the target is an order of magnitude higher with practically just nine months to go.

Of course, there need not be any hardware costs in this case as acquirers do not necessarily have to import point of sale machines and simply go for QR. But both the reach on the merchant end, as well as the underlying tech infrastructure to enable and run those ops, is a challenge, particularly for smaller banks who have absolutely no experience in this business.

In this respect, one recent development looks promising. 1LINK and Paysys Labs recently launched a QR acceptance platform for banks, who no longer have to buy or build tech from scratch. Instead, they can simply integrate with the 1GO platform, allowing them to focus their energy entirely on acquiring merchants.

Going forward

To sum up, all key ingredients seem to be finally in place: government subsidies, regulatory mandates, and tech. Perhaps the only, and possibly the biggest, missing piece of the puzzle remains the capacity and/or buy-in of tax authorities. Without provincial and federal revenue bodies actively supporting digital payment adoption — rather than milking it for hitting their targets — even the most sophisticated payment infrastructure will struggle against merchant resistance. For years, we have seen half-baked measures of documenting the retail economy, but to underwhelming results. Will this time be any different?