If you keep an eye on the global trends in technology and mergers and acquisitions, there’s a good chance that you came across the news of Square — the payments giant owned by Twitter founder Jack Dorsey — purchasing an Australia-headquartered ‘buy now, pay later’ (BNPL) company, AfterPay, for an eye-popping $29 billion. Just a couple of days later, a Dubai-based player in the same industry, tabby, announced a $50 million Series B at a $300 million valuation.

This was barely a span of seven days in the BNPL space, which has been heating up all around the globe for the better part of this entire year. It started from Scalapay from Milan bagging $48m to expand across Europe while the biggest player on the continent and probably the world, Klarna shot to a $46bn valuation on the back of a $639m round led by Softbank’s Vision Fund, the Japanese telecom’s venture arm. Then there is the US leader Affirm, with $1.5bn in the kitty, plus a host of players raising tens of millions of dollars.

This article originally appeared in Dawn.

But what’s the point of throwing all these numbers that have no relevance to Pakistan? Well, that’s because following the hype and the scale witnessed elsewhere, local startups have also started coming up with their own BNPL offerings. That includes QisstPay from Islamabad and KalPay of Lahore, whereas Finpro and KistPay brand themselves as smartphone financing solutions, though in essence, it’s almost the same offering, albeit more specific.

While the name BNPL itself is self-explanatory, let me still clarify the obvious. The offering basically allows consumers to buy stuff from sellers and postpone their payments into the future. The next question is probably: cool, but what’s new in this? Isn’t that what credit cards do after all? Or easy monthly instalments for that matter? Well, they are more or less the same thing as far as the concept of delaying paying for current consumption into the future goes. But there can be differences based on the business model.

Credit cards work on an interest rate model where the financial institution allows the customer to pay for a certain good at any place that accepts cards and pay within a defined time frame to avoid any fees. But once you breach that grace period, markup starts accumulating, and that’s how this channel basically earns banks their profits.

BNPL companies, on the other hand, onboard individual merchants, allowing them to offer their customers the option to extend the payments over a specific period. The most common model is Pay in 4, which essentially spreads out the amount into four equal instalments. Usually, if the buyer is late in repaying, they are charged an interest rate. That’s just the consumer side. These startups also promise to help businesses increase their average order value (AOV) and get them more sales.

Like any evolving space, there is obviously no hard and fast rule, and the models are fluid. For example, QisstPay does Pay in 4 (months) but is absolutely free — not even late payments — to the end customer allowing order sizes ranging from Rs1,500-50,000, according to its founder CEO Jordan Olivas, an American citizen who has previously worked at Klarna and then another BNPL, ChargeAfter.

The merchant receives the full amount upfront while the BNPL player bears the entire credit risk, which they can try to minimise using their customer demographic algorithm, requiring CNIC or some other verification depending on the fintech.

Meanwhile, KalPay gives two options: make the full payment within 14 days of purchase or in four equal fortnightly instalments. However, there are late payment fees “but that too after giving you constant reminders and a cushion period,” says their website.

“We make our money on the merchant side where our platform not only brings in higher-value sales for them but also increases conversion and creates a recurring user base. For the customer, it’s more of a cash flow management system. There is absolutely no markup involved, so it’s fully Shariah-compliant as well,” Mr Olivas says.

While e-commerce continues to be the major channel for BNPL globally — where the buyer simply chooses their preferred option at the checkout — there is also a growing trend of point-of-sale financing. QisstPay plans to do both with some 100 merchants already live for the former while in-store integrations are to come online in a few weeks.

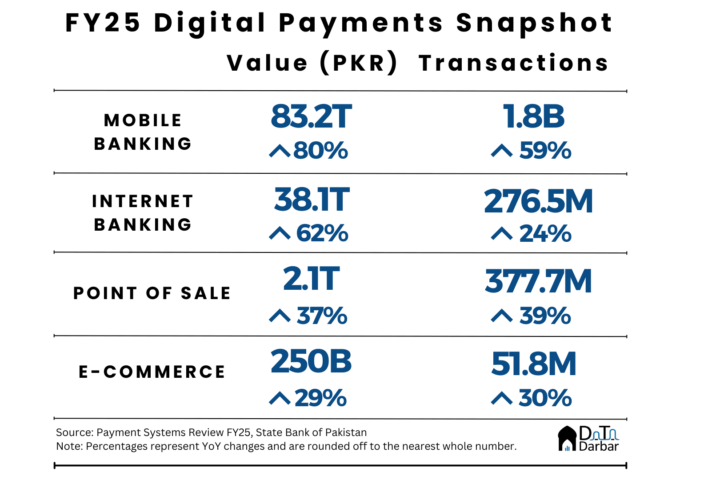

That leads us to what’s the total market these players are eyeing. According to the State Bank of Pakistan’s Annual State of the Economy report, digital e-commerce transaction value was Rs93.8bn — accounting for a 40 per cent share — of which Rs73.7bn came from credit or debit cards. Though the latter is growing at a healthy compounded annual growth rate of over 37pc, it’s still too small a number to make a sound and sustainable business.

Adding the Rs364bn transacted via point of sales in the last fiscal year expands the opportunity size theoretically, but that’s not a channel that has shown much increase over the last few years and the technological sophistication of terminals seems to have stayed the same too. “The latest budget makes it mandatory for retailers to start accepting card payments which open up the market for BNPL, but overall it will take a good five or so years to develop as digital payments proliferate,” QisstPay founder says. Till then, the space will be a venture play, something that at least gives confidence to Mr Olivas who boasts the executives and founders of leading BNPLs among his investors.

There’s also a more philosophical dimension to this entire industry, which is primarily based on the premise of driving consumption, in a country where there is hardly any certainty with respect to the economic situation. Is encouraging individuals to spend beyond their means in such an environment really the race we should be getting into? Perhaps not if you ask me, but that’s probably not going to deter investors from taking this bet.