A few weeks back, I wrote about how AI has pushed capital concentration to recent, if not new, highs across private and public markets. You’d obviously ask why does it even matter? After all, value has always been concentrated in a handful of winners.

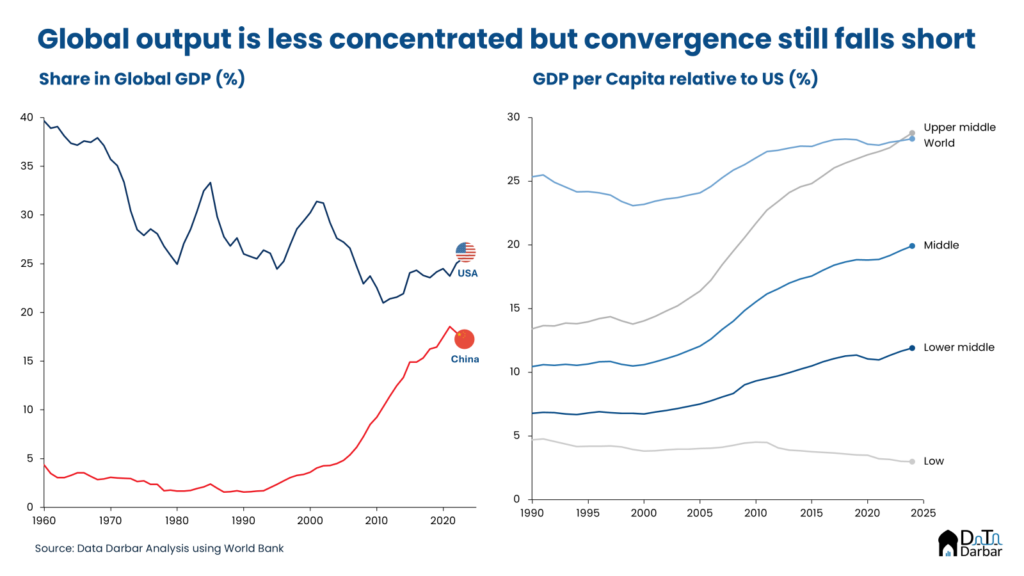

I mean the whole VC asset class is based on this premise and it extends beyond too. Like cricket teams base their game plan around 1-2 star players or that the top 1% of mobile apps drive 80%+ of all downloads. Similarly, even at the global macroeconomic level, concentration has been an age-old theme. For instance, the US accounted for 40% of global GDP in 1960, which has actually declined to 26%. From this lens, things seem more balanced now. In fact, many proponents of globalization do cite this same statistic to highlight how much the world has improved over the last fifty years.

Of course, that’s too simplistic a conclusion since almost the entire share ceded by Washington (13.8pps) was captured by Beijing (12.5pps). Basically, the unipolar economic order gave way to a bipolar one rather than the egalitarian utopia globalists try to portray. Meanwhile, the rest of the world’s contribution to world output has barely moved. Just to be clear, I am not suggesting that other countries — particularly in Southeast Asia, the GCC, Israel and India — haven’t grown or prospered.

But what is becoming increasingly obvious is that at the frontier of innovation and value creation, concentration is accelerating, not diffusing. This strikes at the heart of a theory that shaped development thinking for half a century: that poorer countries would converge with richer ones. It was the product of the post-war, post-colonial era where newly independent nations were still finding their footing and benefited from the advantage of backwardness, as far as growth rates were concerned. As an academic field, dev econ in general drew serious intellectual firepower from this region, with massive contributions from Sen, Haq, Sobhan among many others.

For emerging markets, the traditional development playbook suggested two main pathways:

- build a low-cost manufacturing base and export those goods to richer markets;

- become an offshore tradeable services hub

Other than mineral-rich economies, almost every success story of the past 50 years essentially followed one of these two pathways. Southeast Asia, including South Korea and China, took the former route while India’s rise was rooted, in part, in the services offshoring boom. Both of these options are at risk today because of AI.

Manufacturing

Traditionally, labour arbitrage coupled with weak currency enabled economies, particularly in Southeast Asia, to industrialize and build a low-cost manufacturing base. This not only helped create jobs at scale but also provided with forex buffers.

While the model is not yet broken, it nevertheless faces major headwinds on top of a structural limitation that long predates AI. According to the World Bank, 108 countries remain stuck in the middle-income trap — including economies that industrialised successfully, as their cost advantage eroded faster than their productivity advanced. Only 34 have crossed that threshold to reach “high-income” status since 1990, with a combined population equal to Pakistan’s, of which a third either joined the EU or struck oil. And now, other pressures also mounting up.

First, the supply chain disruptions post-Covid made the risks of offshoring too obvious. Second, and more importantly, the broader pullback from globalization and the tariff wars have pushed developed markets to consider reshoring. Currently, it is still cheaper for firms to rely on labour from developing countries but as advancements in robotics materialize, the calculus will change.

Meanwhile, high-value manufacturing, particularly in sectors like electric vehicles, batteries, and renewable energy, is already highly concentrated. Particularly so in China, which has built supply chain depth and scale that other countries find extremely difficult to replicate.

Services

This second pathway, service exports, powered India’s growth and created BPO industries across the Philippines, Malaysia, and Latin America. It’s here we see the most immediate risk as genAI has upended the entire model on its head and drastically changed the economics. Knowledge work is no longer the same as most top models, including Claude and GPT variants, comfortably surpass what your average worker produces, adjusted for price and delivery timelines.

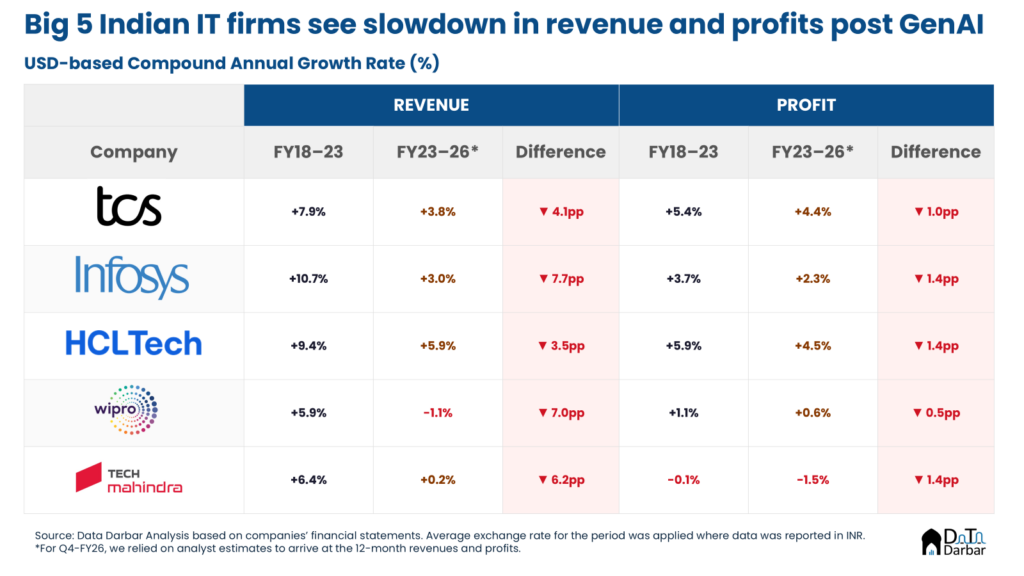

Over time, things will obviously become clearer as to the exact impact but early evidence doesn’t paint a great picture. Since March 2024, i.e. when Claude Opus 3 came out, the big 5 Indian IT firms – TCS, Infosys, Tech Mahindra, HCL Tech, Wipro – have seen a median stock decline of 18.6%. More worryingly, business has slowed down, with a noticeable decline in growth rates of both revenues and profits.

Sure, correlation is not causation, and there could be multiple reasons behind the slowdown, including post-pandemic spending correction. However, dismissing the signal entirely would also be a mistake. While some of these large enterprises may end up finding ways to reinvent themselves, the outsourcing pitch is not going to be the same millions of firms and freelancers in the age of genAI.

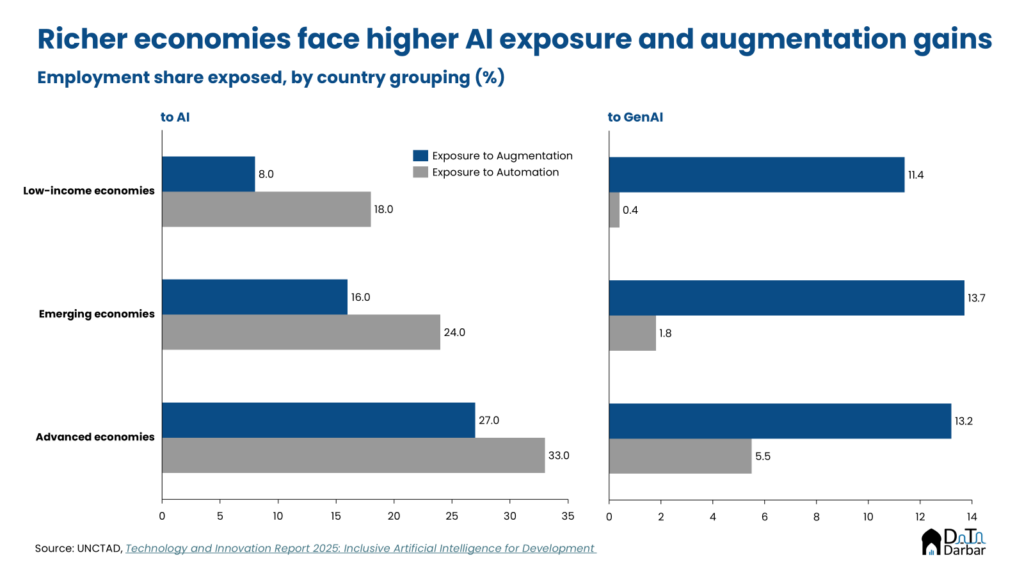

The oft-cited counterargument — that workers in these economies can simply upskill and learn to use AI — is not particularly comforting either, to me at least. Eventually it boils down to the whole augmentation versus substitution argument i.e. what share of jobs can gain from AI via productivity boost as opposed to getting replaced by it.

In “Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work”, the IMF proposes a conceptual framework that assesses countries and occupations based on the level of exposure and complementarity. Given the structure of labour markets, it naturally finds advanced economies to be more at risk while emerging markets are considered less vulnerable. However, that’s largely because workforce is overwhelmingly employed in primary industries. So even if those jobs are not particularly threatened in the near future, they still typically have lower per-capita output compared to the export-oriented services sectors.

No way out?

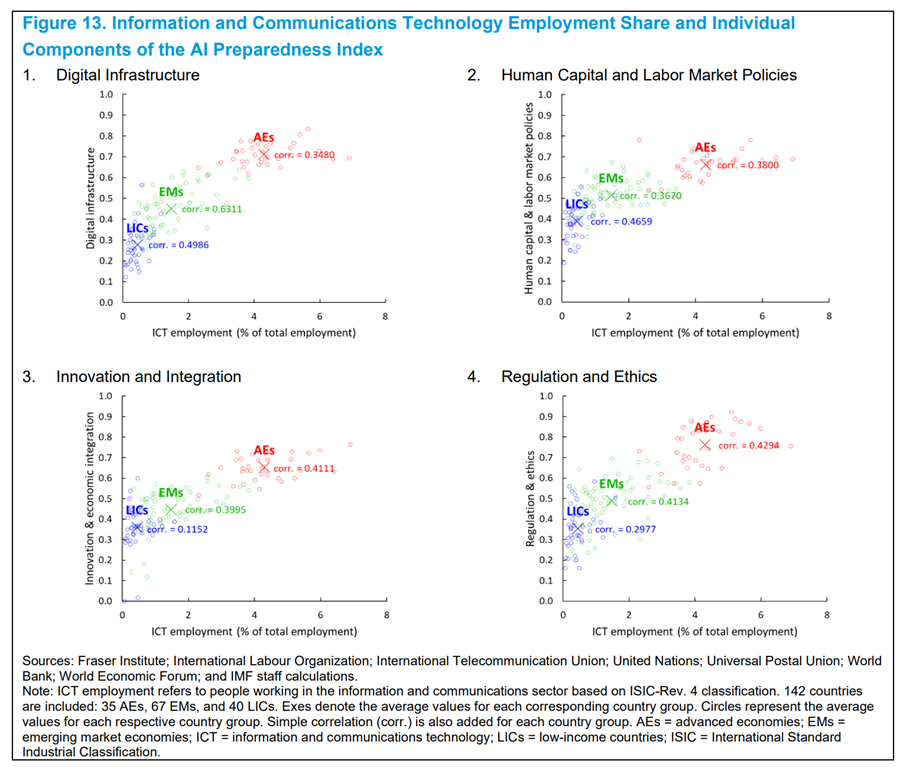

The irony is that the escape route from both runs through the same door: frontier technology. But building that requires access to capital and compute at a scale that is itself increasingly concentrated in a handful of geographies. Not to mention that the financial returns from these investments would inevitably flow to the advanced economies through the capital income channel, only further widening the gap.

It all brings us back to where we started. The convergence thesis rested on two assumptions: that technology would diffuse outward over time, and that latecomers could always find something (essentially, cheap labour) to sell. For now, AI seems to be breaking both.

There is, of course, the possibility that this is all noise: perhaps another tech cycle running ahead of its fundamentals and will eventually correct course. And to be fair, for all the capabilities shown, the hard impact on global output or growth due to AI is yet to be seen, something Nadella alluded to recently. But that’s beside the point: as long as enough people building and investing at the frontier of tech believe in its unfettered potential, capital and talent will concentrate and the risk of divergence only amplifies.