December might be the month of festivities in many countries but for corporates, it’s anything but. The period is marked by employees rushing to meet targets — often by hook or crook. Not too unlike students making last-minute efforts to ensure a good grade the night before the exam. This practice of window dressing has a rich history in Pakistani banking, something we have written about a number of times.

Read: How banks dodge ADR tax with this cool trick

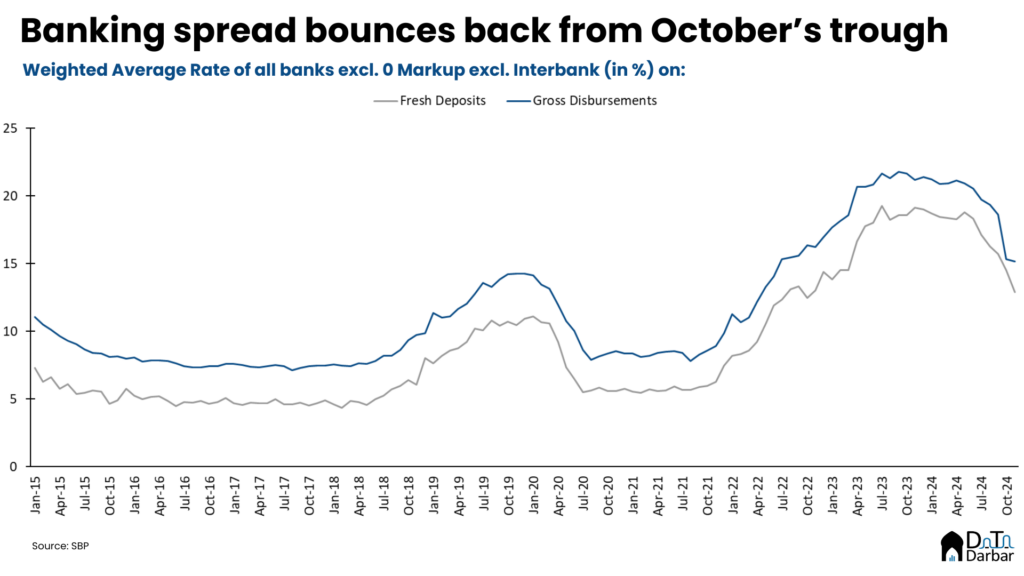

However, the window dressing of the last few months was on a different scale, as the industry faced a gap in advances of around PKR 4T to be plugged in just four months. Finding that many debtors in such a short window was difficult, so banks had to be competitive and underwrite less lucrative deals. As a result, the spread between gross disbursements and fresh deposits plunged to a low of just 80 basis points in October — the lowest since at least 2011. To state the obvious, the monetary policy decision also played a role here. Since then, the gap has recovered, reaching 221 bips the following month.

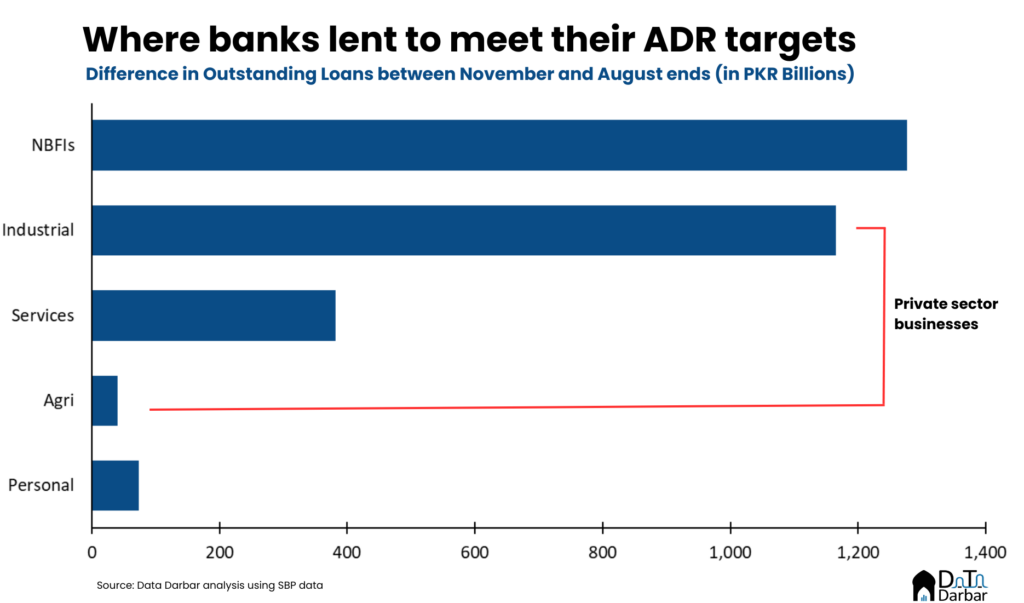

In this hour of need, banks turned to the less coveted financial institutions and gave them more money than they’d ever seen on their books. By November end, the outstanding loans to NBFCs had reached PKR 1.46T, almost 6x compared to where it was in June. Some funds also found their way to private sector businesses, which reached PKR 8.9T in November — PKR 1.6T higher compared to August’s trough.

Where the money flowed

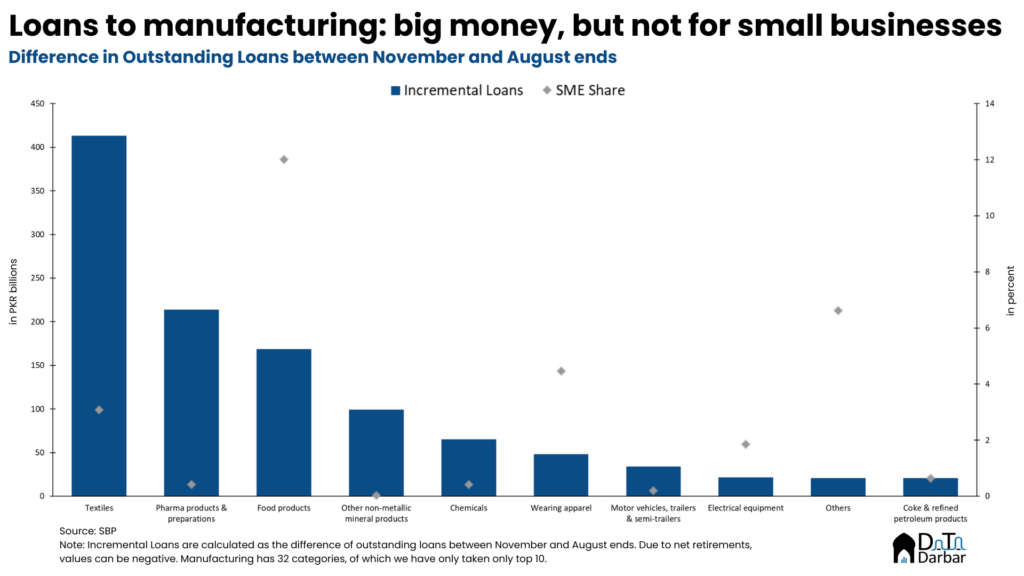

Unsurprisingly, the big businesses were the biggest beneficiaries of fresh loans. In the non-SME category, loans are heavily concentrated in manufacturing, accounting for PKR 1.1T in incremental financing — accounting for almost 71% of private sector businesses’ gross disbursements between August and November ends. Of this, food producers got PKR 148.5B, with rice processing units securing almost PKR 61.0B and manufacturers of bakery items PKR 76.9B.

Predictably, textile came out as the biggest net borrower with incremental advances of PKR 400.4B during the period. Other major beneficiaries included manufacturers of chemicals at PKR 64.9B, pharma PKR 213.0B, and non-metallic mineral products (like cement) at PKR 99.3B.

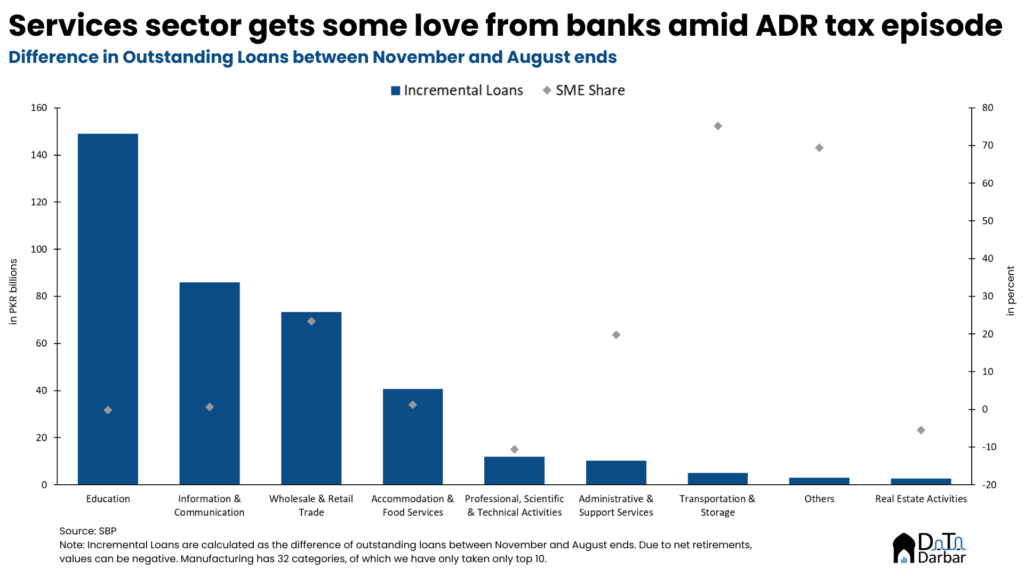

On the services side, wholesale and retail trade received marginal financing of PKR 56.1B and hotel and accommodation PKR 39.5B during the period. Information & communication was also a prominent borrower, likely due to the presence of large, credit-worthy players in mobile and internet. However, the biggest surprise was education, with net loans of PKR 149.7B — compared to the average monthly outstanding loans of PKR 25.3B between July 2019 and June 2024. Meanwhile, agri wasn’t lucky and only managed to obtain just PKR 39.8B, representing an increase of 11.6% over end of August value.

It poured some on SMEs too

When it rains, it pours — with few drops even sprayed on small and medium enterprises. By November, loans to SMEs reached a record PKR 624B — up 12.1%, or PKR 67.3B, compared to August-end level. However, this growth was 10 percentage points slower than non-SMEs. The list of major beneficiaries was pretty similar with manufacturing receiving 61.7%, or PKR 41.5B, of the total financing while agri actually saw net retirements.

Relative to overall fresh loans, SMEs only got just over 4%, lower than their share of 7% in outstanding financing. However, beneath the big numbers, you see glimpses of hope, albeit marred by window dressing. In terms of absolute values, small grain mill producers received the amount of PKR 21.3B, or almost 26% of the marginal loans to the sector during the period. Small wholesale & retail players also got PKR 17.2B, just under a quarter of the sector’s total new financing. In third place were textile SMEs at PKR 12.7B, though their sectoral share was a dismal 3%.

Eventually, none of it really mattered as after lots of pressure, the government replaced the tax on low ADRs with a higher flat rate of 44% on overall profits. This whole situation was quite interesting to say the least, with one party introducing half-baked and distortive measures while the other hell-bent on doing everything in their stead to avoid extending loans.

Scapegoating the macros

But the bigger, and more common, question is why they are so averse to credit? A range of explanations are offered to explain this phenomenon, with most revolving around the role of the government, which currently runs a fiscal deficit of 7.36% or the elevated interest rate, despite the recent easing. To be fair, these arguments have merit: after all, the monetary and fiscal indicators have an outsized impact on the financial system. But do the macros really explain our situation?

Contrary to the popular perception, there is a large group of countries, especially emerging markets, with persistently high fiscal deficits and double-digit policy rates. Do they also exhibit a similar banking culture of risk aversion where banks deploy almost every single deposit into government securities?

At the risk of oversimplifying things, the argument from those sympathetic to banks is: the government cannot keep its fiscal operations in balance (or under a deficit of the 3%) and has to turn towards local financial institutions to plug the gap, thus leaving little liquidity for businesses and individuals. Essentially, there should be an inverse relationship between banking exposure to private sector (or inversely, government) should be a function of sovereign debt and/or fiscal deficit.

Our macro troubles are far from exceptional

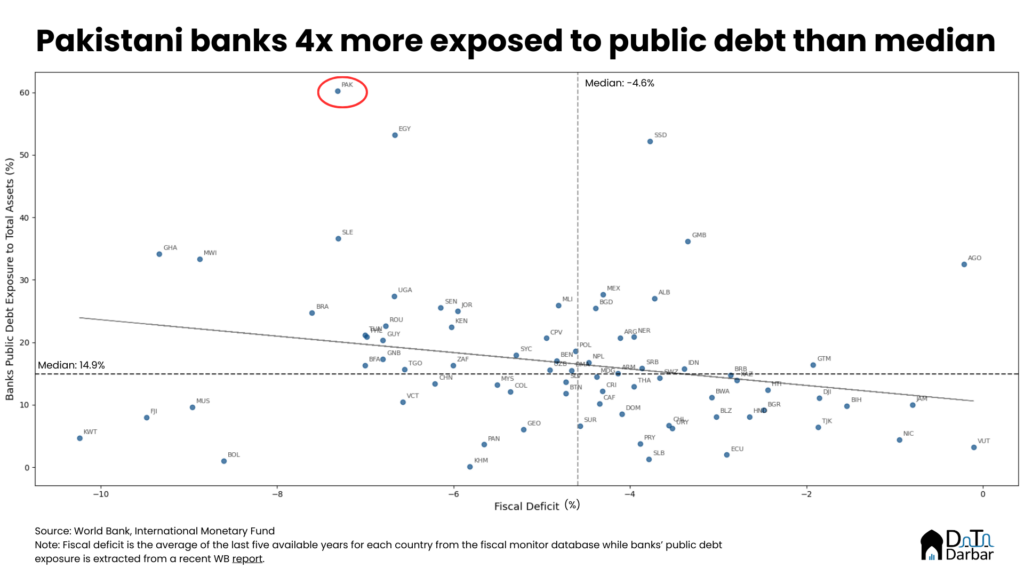

Luckily, there’s actual literature on the topic: the World Bank recently highlighted the issue of Sovereign-Banking nexus and its associated risks. Between 2012 and 2023, the exposure of banks to government debt in debt-distressed emerging markets and developing economies rose from 13% to 20% of total bank assets on average.

While it’s a broader problem across EMDEs, Pakistan stands in a company of its own with banks’ public debt exposure as a percentage of total assets at 60.27% — ahead of second-place Egypt by 705 basis points and higher than the sample average of just 16.75%. Is it because Islamabad borrows too much? Not exactly: Egypt has a sovereign debt to GDP of 92.68% while we are within one standard deviation of the mean at 76.57%.

Just to play around, we ran a basical statistical analysis between banking exposure to public debt and fiscal deficit. Once again, there was very little to take away as the correlation coefficient was a weak -0.25 and the regression didn’t exhibit any statistical significance either.

In other words, our fiscal and debt indicators, bad as they may be, are still within a reasonable range of average. However, the same can’t be said about Pakistani banking, whose dependence on the federal government to keep afloat is highly unusual. Of course, nothing here is new information and even the most ardent of hedge funders bankers know it, even if loyalty to their jobs and lifestyles demand otherwise.