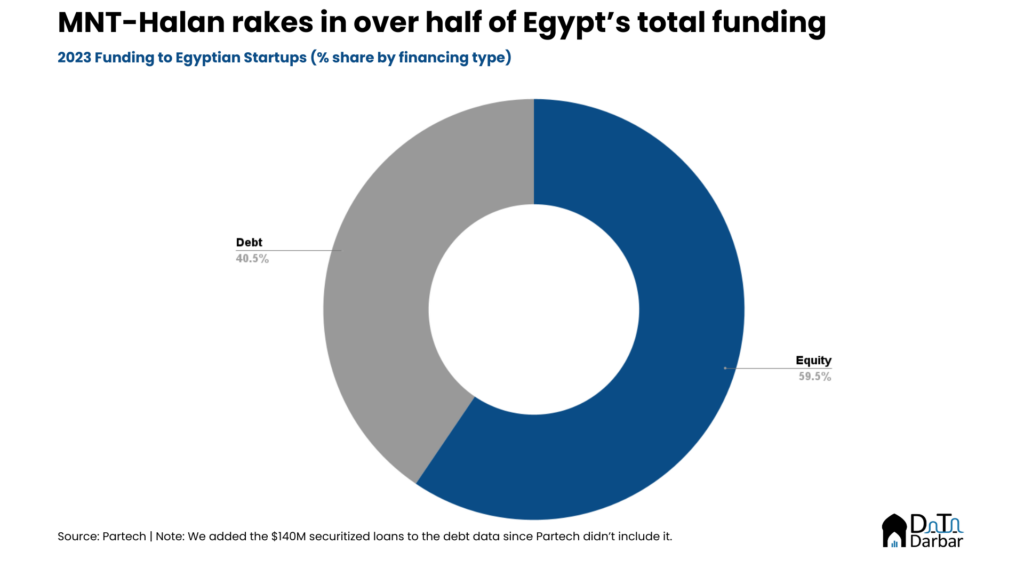

No one could have guessed that a ride-hailing startup would become the most prominent fintech name in Egypt. But then, MNT-Halan’s journey has been unpredictable. In a market where capital is still scarce, it has raised $677M+ through a mix of debt and equity. For context, that is over a quarter of what the country has managed to raise in total since 2018.

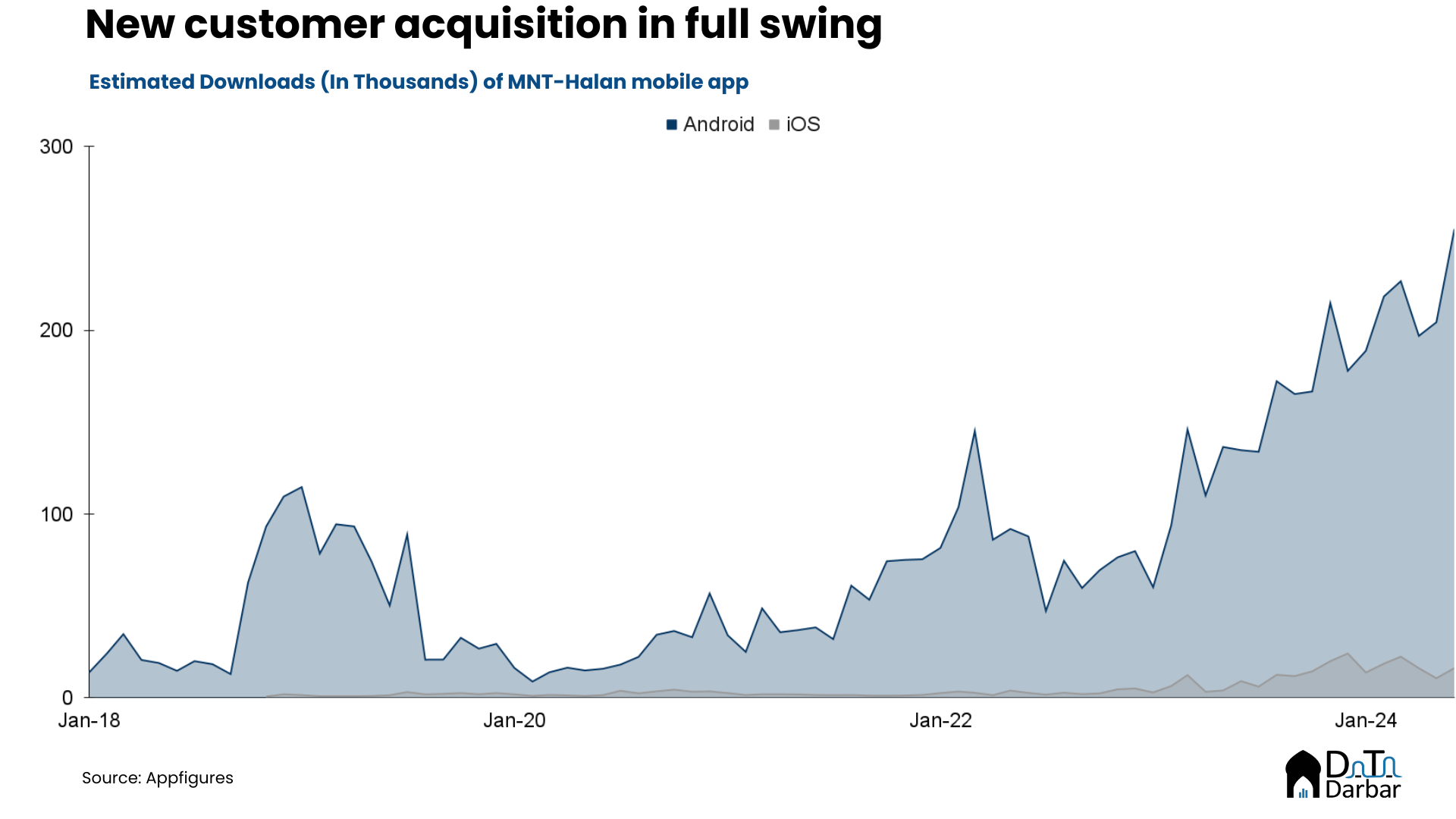

In a little over five years, MNT-Halan claims to have become Egypt’s largest non-bank lender to the unbanked. It boasts more than a million monthly active customers and a 21.7% market share. To date, it claims to have disbursed over $4.4B in loans and possesses micro consumer and nano finance licenses from the Financial Regulatory Authority. Additionally, the startup was the first to get an independent electronic wallet license from the Central Bank of Egypt, enabling digital disbursement, collection, and transfer of money via mobile app.

With its home market covered, and a fresh funding round of $260M equity and $140M debt in February 2023, MNT-Halan wanted to go global and Pakistan became its next frontier. The following month, they acquired a 100% stake in Advans Pakistan, a licensed microfinance bank, from its parent company, S.A. Sicar.

Though neither party gave any guidance on the transaction price, we believe the amount would be rather small. As of 2023, Advans Pakistan had net assets of PKR 645M and the median P/B for listed banks has been <1x for a while. This gives us at least some idea about the underlying value, if not the price itself.

In March 2024, the shares of Advans were finally transferred to MNT-Halan after all the regulatory approvals, including from the Competition Commission of Pakistan. With legalities sorted, it will now look to replicate past successes in a completely foreign market on the back of a license which equips them with the mandate to offer all possible financial services, from payments to lending. On top of it, they have direct access to an existing customer base, staff, and a branch network.

A perfect deal?

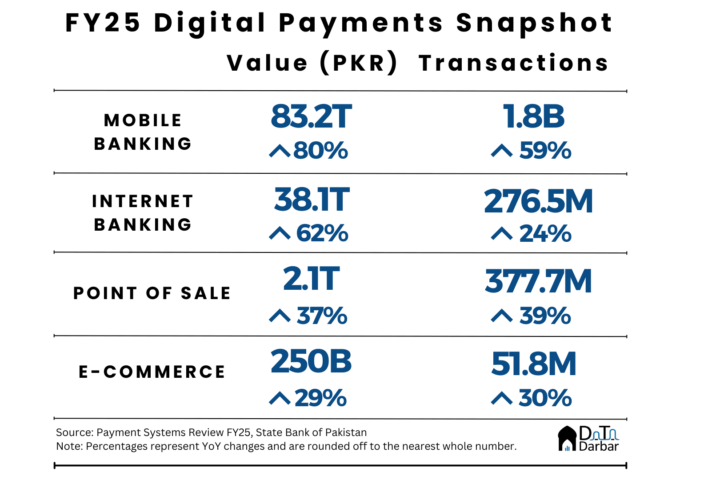

From that perspective, the acquisition appears quite promising.Throughout the last decade, microfinance banks have witnessed a significant surge in their deposit base, both in value and the number of customers. By December 2023, the total value of deposits had soared to PKR 596 billion.

This uptick is largely driven by the prevailing high-interest rate environment, which has incentivized more people to entrust their money to the formal banking system and earn a decent yield.

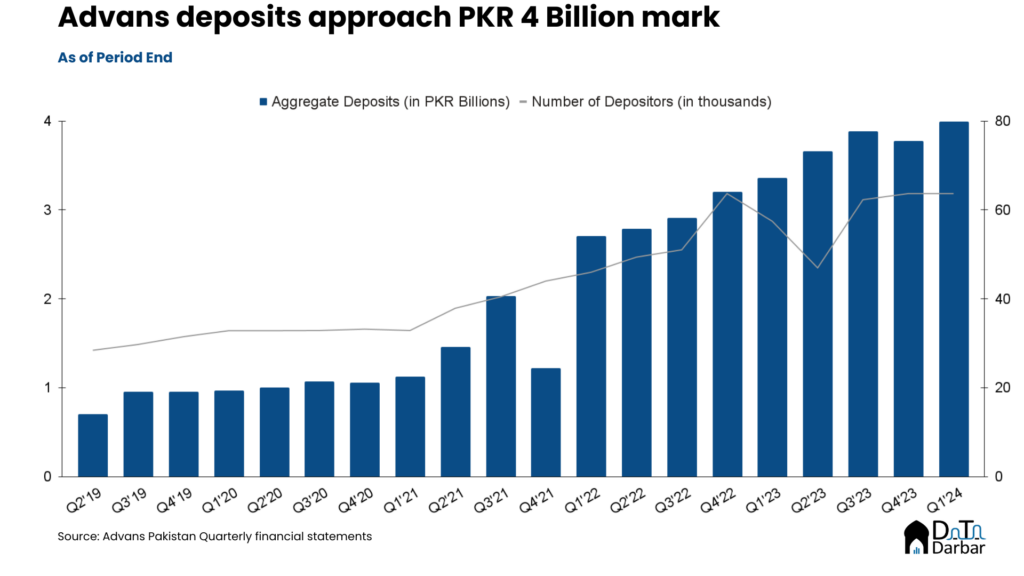

Advans Pakistan is no exception, showing a consistent rise in total deposits every quarter. The bank has reported an average 14% growth in the total value of deposits and 6.5% in the number of depositors. This was primarily on the back of fixed and savings instruments. They collectively accounted for 98.4% of the overall deposit mix in 2023, up from 96.7% in the previous year.

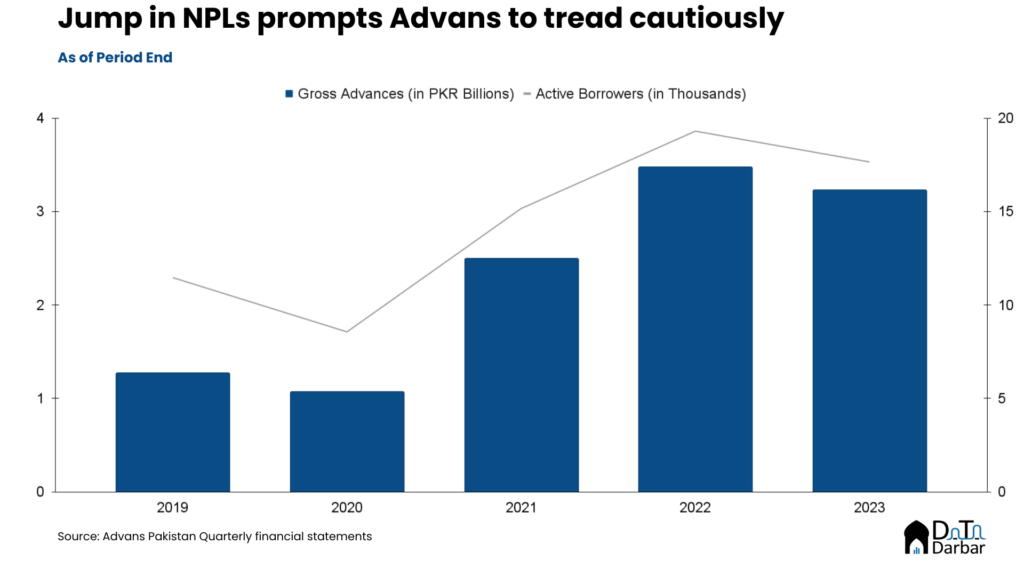

In 2023, gross advances saw a sharp drop of 7.24%, driven by an economic slowdown and elevated benchmark rates. This economic climate led to a 9.3% reduction in the number of active borrowers, which fell from 19,302 in 2022 to 17,925 in 2023. A large portion of APMFB’s loan portfolio is made up of unsecured loans, amounting to PKR 3.1 billion, making up 97.1% of the total portfolio for 2023 which poses substantial credit risk and the potential for future non-performing loans (NPLs).

The Devil is in the Details

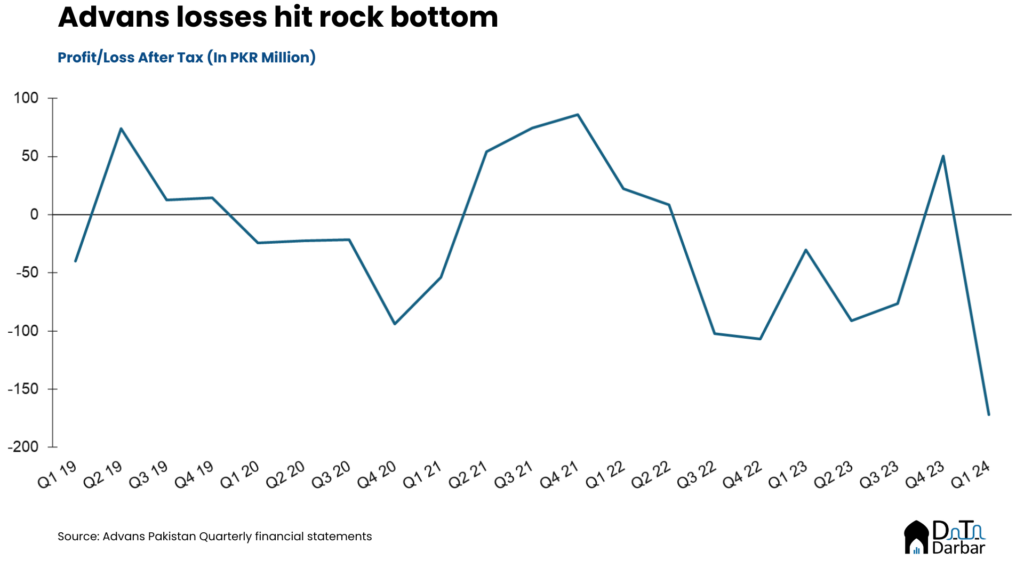

While these figures paint a promising picture, the full financial story reveals a mix of challenges and opportunities. Despite impressive growth in deposits, there are notable downsides that warrant attention. After all, the journey of Advans is far from straightforward, just like the broader sector. In 2023, the bank’s total markup income jumped to PKR 1.7B, from PKR 1.3B in 2022. This was thanks to a 5pps jump in yield on earning assets, attributable to the high benchmark rate. Meanwhile, the cost of funding also rose 8pps to 22.6%, compressing the spread even as net interest earned edged up slightly.

Non-markup income also jumped but wasn’t enough to counter the increase in corresponding expenses. As a result, net loss clocked in at PKR 178M in Q1’24, pushing accumulated losses to PKR 1.26B. These figures aren’t surprising since the bank has struggled with profitability since the 2022 floods, which particularly affected Sindh. All of Advans customers are located in the province, thus significantly impairing the ability of its borrowers to repay their loans. Consequently, non-performing advances increased by an average of 12% quarter on quarter. Although the bank is correcting course, with the infection ratio slightly improving, the weather isn’t clear yet.

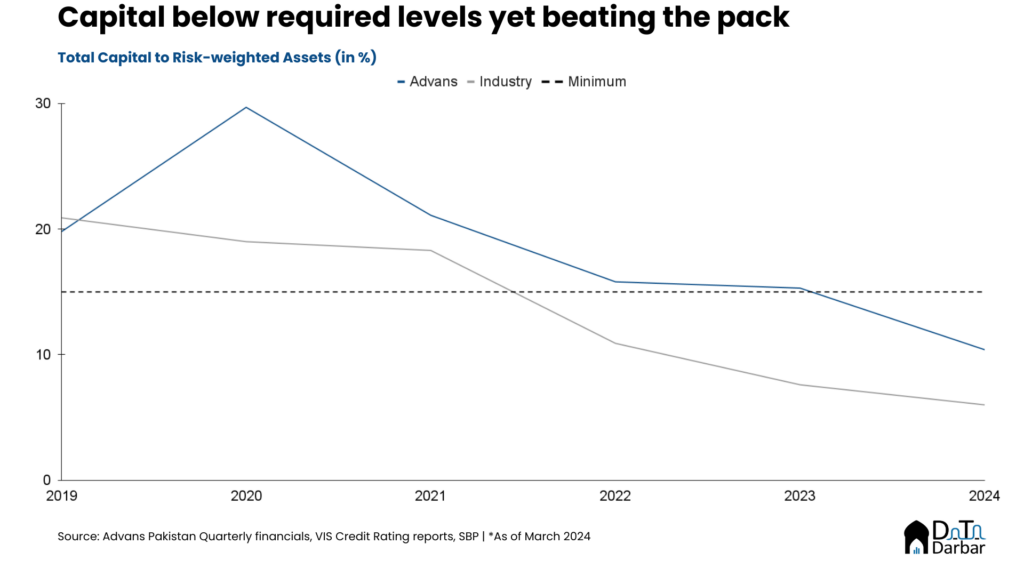

Bad debts and resulting losses have taken a toll on the Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR), which fell to 10.93% by Q1’24 — below the minimum required of 15% though still higher than the industry’s 6%. This was a long time coming as even back in March 2023, Advans had appealed to the State Bank of Pakistan for a waiver regarding CAR compliance. However, this request was not granted and the sponsors had to inject equity: the first tranche of PKR 188.5M on August 15th, 2023, and the second of PKR 132M on September 12th. According to its credit rating from April, the new shareholders plan to invest PKR 1-1.5B to shore up capital buffers.

Why Advans?

You might be wondering why a unicorn is taking over a struggling bank? One that doesn’t even meet the minimum capital requirements. What’s the motivation here? After all, Advans is a minor player, accounting for <1% of the total MFB net portfolio — only bigger than Sindh MFB. Thus far, the MNT-Halan team has remained tight-lipped about what they plan to do in Pakistan. But if their success in Egypt is any guide, the answer lies in the use of technology. And that’s where Advans appears to stand out, well sort of. Not because of any moat, but because it comes with the least baggage.

Pakistan’s microfinance sector has traditionally presented itself to be the champion of the underdogs. Unlike commercial banks which tend to be risk averse and concentrated in urban centers, it has built a customer base in the peripheries and catered to segments who otherwise wouldn’t be able to access formal financial services. This is only possible through an informal touch by relaxing the paperwork like salary slips or house documents. Instead, the sector relies on proxies such as the count of cattle, guarantees from the community, etc to assess risk. At the heart of it stand loan officers, who are relationship managers and are involved in the clients’ lives.

Less is more?

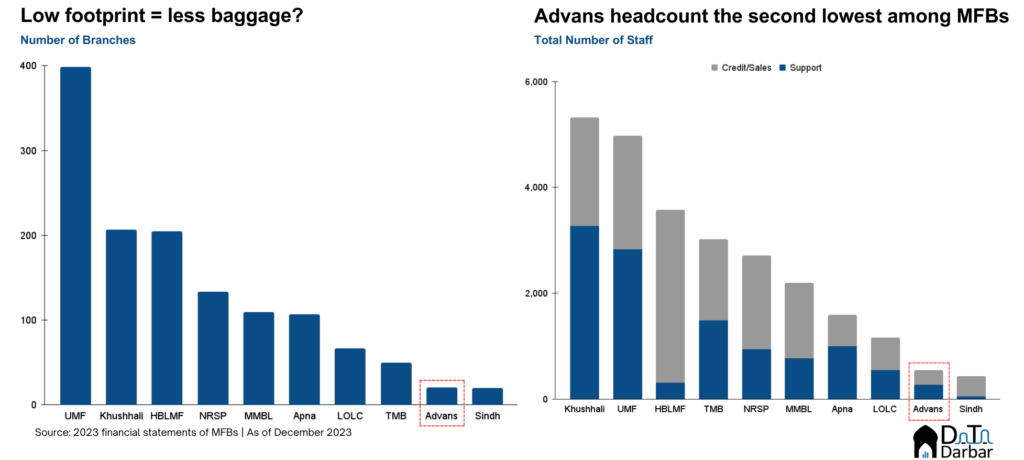

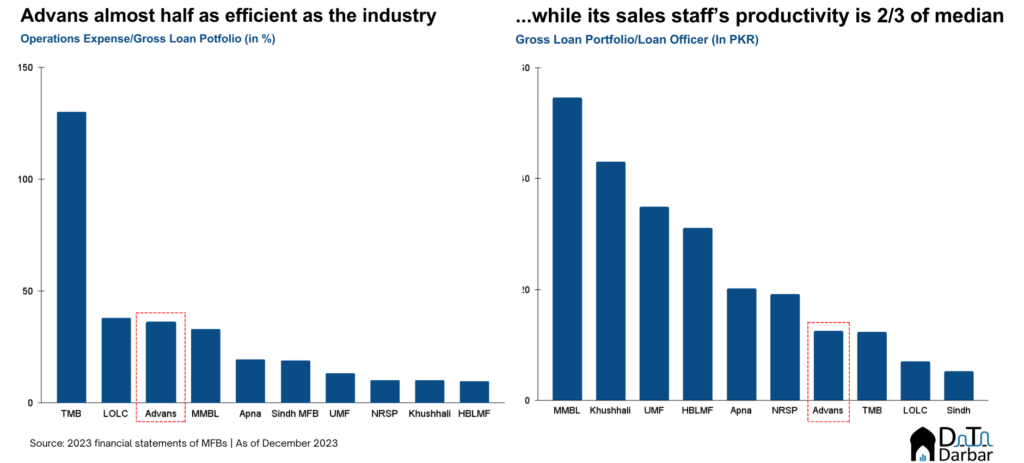

It’s a simple input/output equation: add in more locations and credit officers and drive growth. However, Advans has always shied away from taking that path. With just 20 branches, it has by far the smallest footprint in the sector and operates in only 11 districts. The closest is Sindh Microfinance Bank with the same number of branches but over 3x locations through service centers. Similarly, its headcount of 538 was the second-lowest in the industry, only ahead of Sindh Microfinance Bank’s 426. Meanwhile, the number of credit/sales support staff was 258 and behind everyone in the industry. Moreover, Advans lacks any digital footprint at all: not even ATMs, let alone a mobile app.

This can essentially be the advantage of backwardness by potentially saving significant restructuring costs. Few people, fewer branches, and virtually no technology allow MNT-Halan to almost start from scratch. As per its credit rating report, the new management is looking to expand across Pakistan after implementing core banking software and launching new products. Apparently, they also want to increase the number of loan officers and branches. This is counter-intuitive, to say the least, not only because MNT-Halan specializes in technology instead of on-ground operations. If the strategy is to take the brick-and-mortar route, that will not only require serious money but also streamline the existing inefficiencies.

For MBFs with data available, Advans’ operating expenses to GLP ratio of 36% was the third-highest in the industry and almost twice the median (19%). Moreover, the organizational structure is skewed, with more banking/support staff for every credit/salesperson. This essentially means the majority of human resources is involved in administrative tasks instead of growing the business directly. Unsurprisingly, it stands towards the lower end based on outstanding portfolio-to-credit staff.

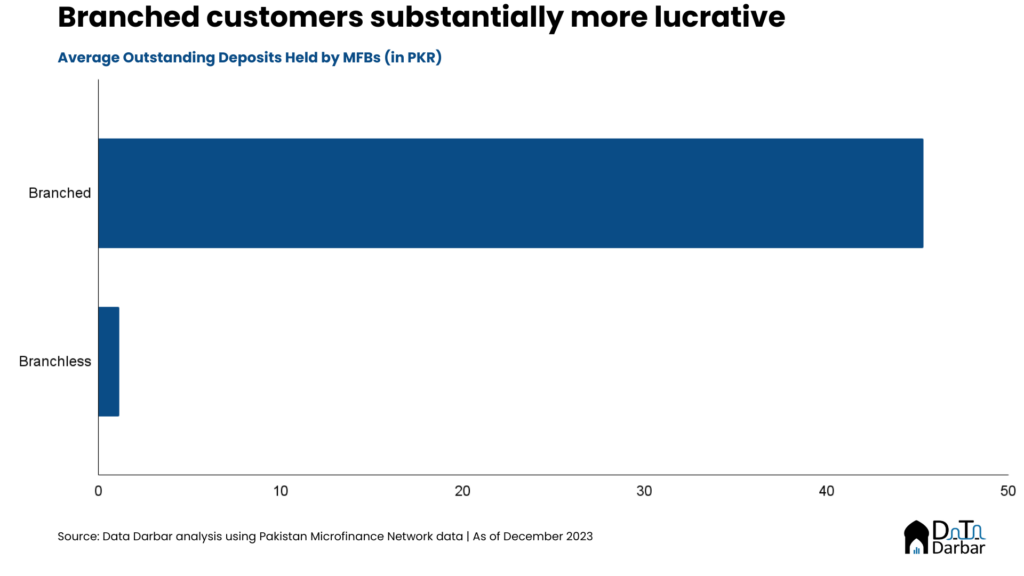

Scaling the physical network can have its advantages though and allows for not only trust but also higher deposits. According to our analysis, the average deposit amount in branched accounts was over 39x compared to branchless. This has been the bane of many digital wallets who, despite millions of users, struggle to monetize payments.

That said, it’d still make more sense if MNT-Halan takes a similar approach as EasyPaisa or JazzCash, who essentially leveraged the microfinance license to first build an agent network before transitioning towards mobile banking. But digital isn’t a piece of cake either. After bleeding for years, the former finally turned profitable in 2023 thanks to nano credit. The bank has aggressively pushed digital lending and disbursed loans worth PKR 36.4B in H1’24. Though updated numbers for the latter aren’t available, it also boasts a sizable book. Now keep in mind that their respective parents arguably had the richest data on Pakistani consumer behavior, on top of positive cash flows and extremely strong sponsors.

Foreign, yet no stranger

With yet another round of funding, MNT-Halan has no dearth of money either and can afford to be aggressive with growth and patient with profitability. However, as we have found time and again, the Pakistani market, especially in tech, has a thing for testing patience in more ways than one can imagine. Especially if you are a foreign player and need dollarized returns. Many a big name have experienced this the hard way. But then, coming from Egypt must have already prepared them for all the possible challenges they await here.