Around the world, financial services professionals — particularly some variety of bankers — are known for their haughtiness. Prestigious schools, inhumanely rigorous training as analysts, and partying at expensive clubs and yachts all help build that reputation. But the fact that they handle and allocate so much capital at least somewhat justifies it. Somehow, the same arrogance found its way through to banks in Pakistan, despite their lack of pedigree or ability to actually arrange and allocate capital. But that’s because they don’t need to do any of that: there is always sovereign knocking at their doors in search of funds while offering juicy riskless returns.

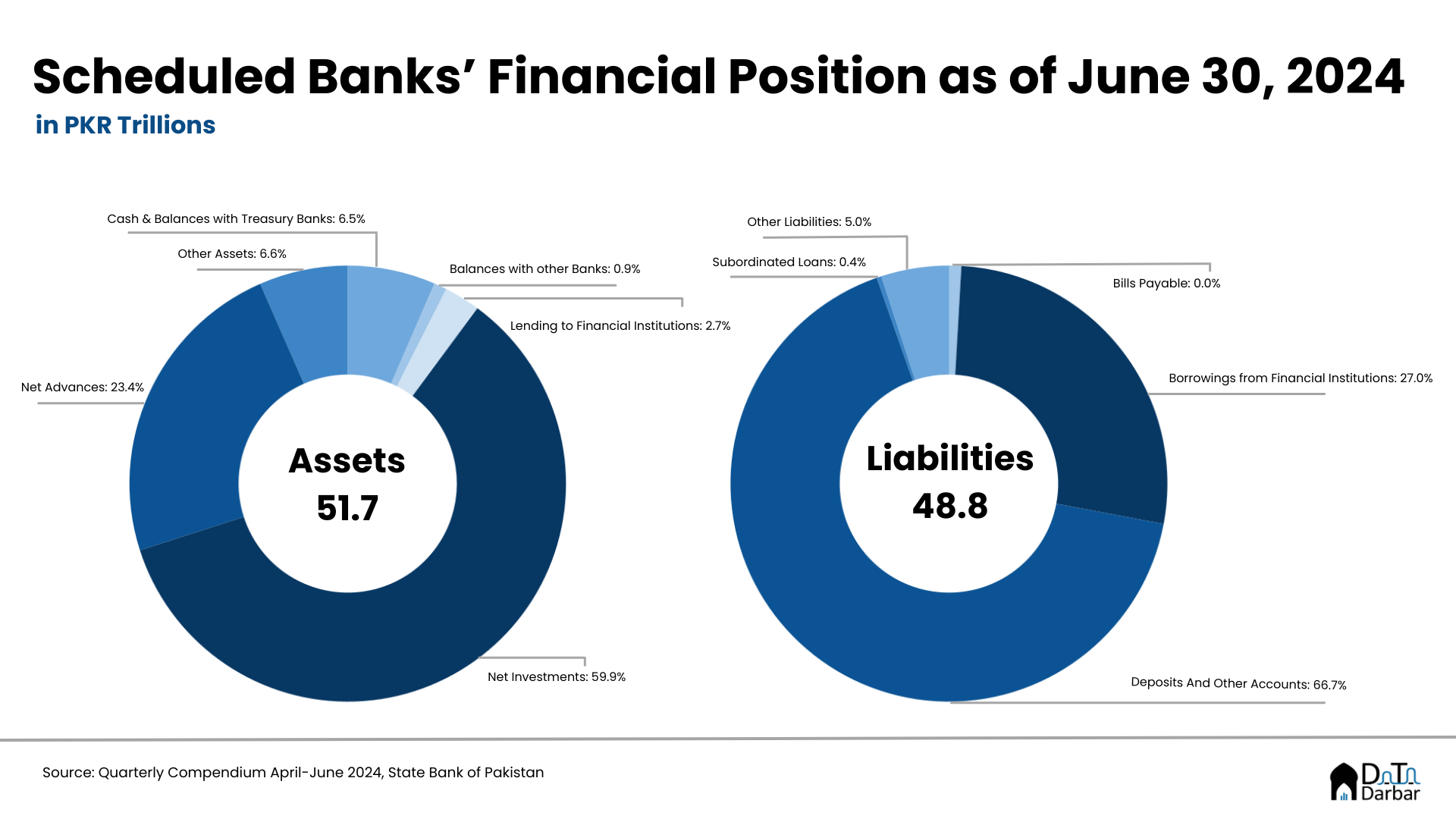

What you end up getting is a sector with record profitability, while taking minimal risks. It’s almost like the wisdom we hear about software-as-a-service companies on LinkedIn. Between FY21 and FY24, the asset base of Pakistan’s banking has ballooned by PKR 23.5T to reach PKR 51.7T — an average year-on-year growth rate of 22.3% each quarter.

Out with deposits, in with borrowings

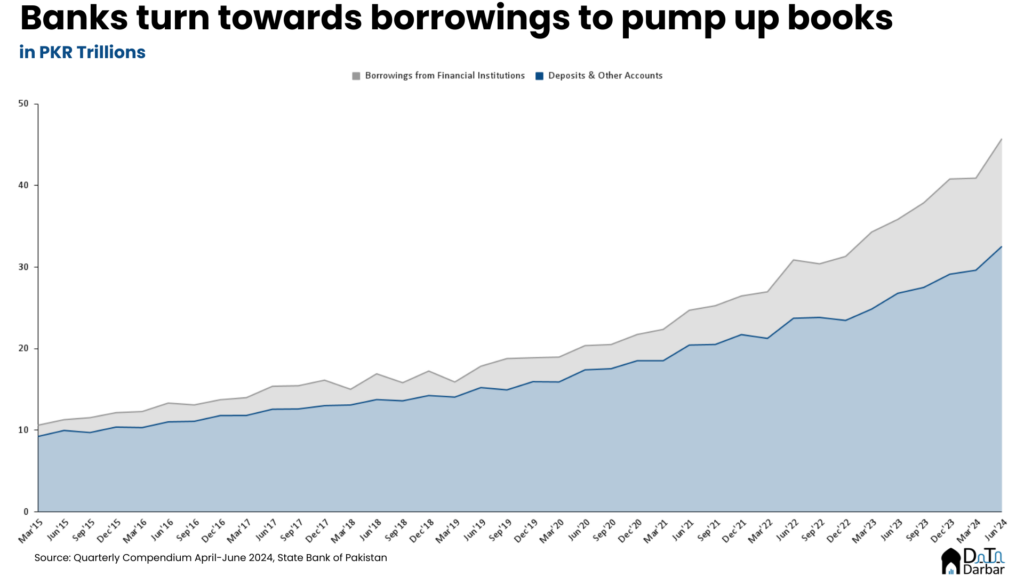

The composition of liabilities was a lot more interesting. Typically, banks rely on mobilizing deposits from customers, both individuals and organizations, which is then used to make loans or investments i.e. assets. This mandate of collecting funds from people is what makes banking the most attractive license in financial services. A decade ago, these deposits accounted for almost 82% of all the liabilities. But for the last few years, the split has changed considerably.

As of June, the share of deposits in total liabilities for banks in Pakistan had fallen to two-thirds, while 27% came via borrowings from other financial institutions — having increased by PKR 8.9T between FY21 and FY24 to close at PKR 13.2T. This includes the State Bank’s repurchase agreements or repos, which have become quite popular of late.

Leveraging on steroids

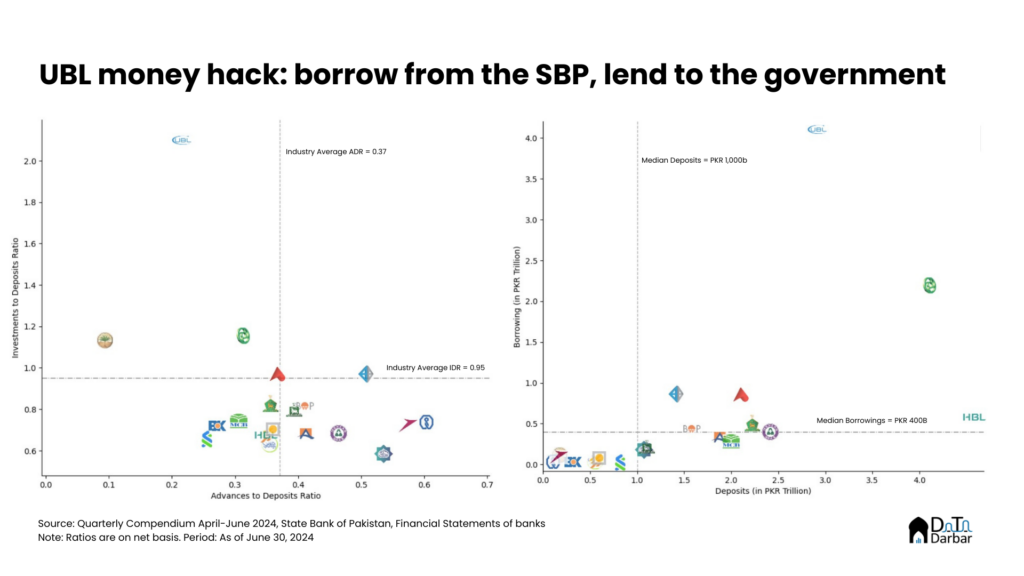

However, the aggregate numbers don’t tell the whole story. Within the industry, there’s a lot of variance where UBL stands out with no comparable whatsoever. As of June, it had borrowings from other financial institutions worth PKR 4.1T as against deposits of PKR 2.9T. If it’s not already obvious, this mix is extremely unusual with borrowings over 10x the median industry level. Put another away, only 40% of its liabilities were deposits, almost half of the industry’s median.

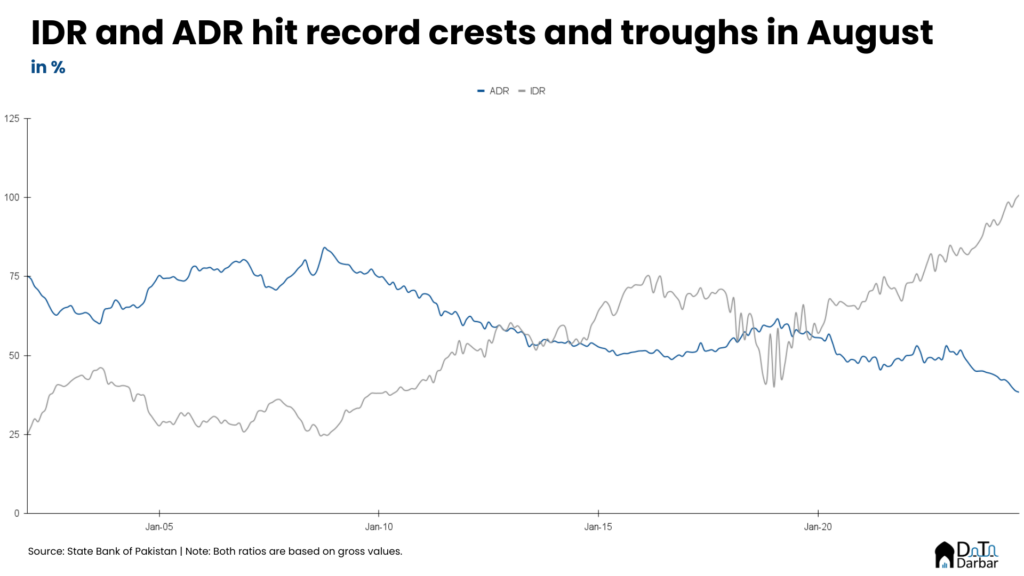

This split has implications on the assets side where UBL boasts an investment-to-deposits ratio of 210%. Pause here for a second and appreciate how insane the figure is. Banking in Pakistan as a whole is already operating at 95% IDR, which would raise eyebrows anywhere. But then you have an institution so desperate to put money in teasury instruments that it has leveraged itself by over a 100%.

On a gross level, where we have monthly data from January 2002, banks in Pakistan saw IDR cross 100% in August for the first time and closed at 100.8%. While the industry is bad regardless, some banks are more responsible for such a situation. The main culprits here are UBL and NBP: given their size, these two can swing numbers substantially. Combined, they had gross investments of PKR 10.8T, or almost 35% of the industry total.

Again, UBL is a particularly interesting case because it alone accounts for a massive 19.6% of scheduled banking investments while its share in gross advances is just 5%. This translates into ADR of just 21.5% – almost 15pps below the industry’s lowest level. Surprisingly, it’s not the worst performer still: that title goes to BML, erstwhile Summit, which obviously shouldn’t come off as a surprise to anyone. Plus, given the size, it has barely any effect on industry aggregates.

Income Statement

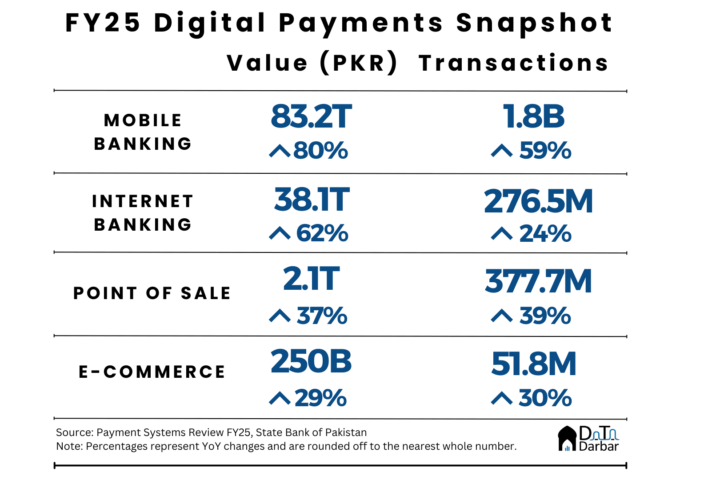

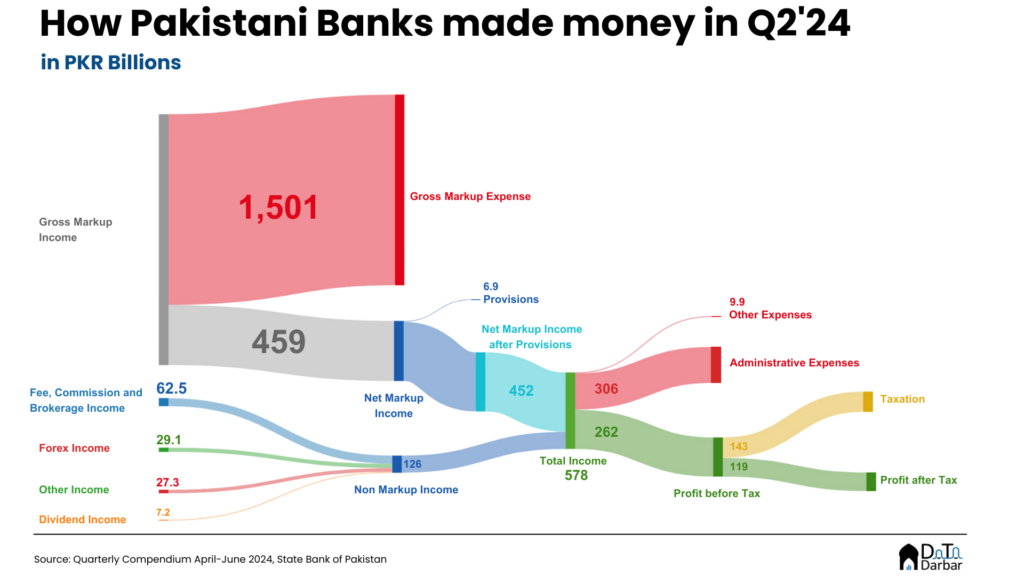

I think we have talked enough about the messed up nature of balance sheet, particularly UBL’s. Now let’s move towards the profit and loss side, where the effects of monetary policy are blatantly obvious. Starting off, gross markup clocked in at PKR 1.96T in Q2’24, up 4.37% over the preceding quarter and 30.2% compared to the same period of the previous year.

However, there are now finally some signs of tapering off as the SBP accelerates monetary easing, most recently cutting the policy rate by 200bps to 17.5%. This is clear across major line items, including the net interest income after provisions of almost PKR 452B in April-June. While the figure was higher compared to the same period of the previous year, it was lower than the preceding three quarters.

Total non-markup income also witnessed a similar trend as it jumped 31.9% YoY to PKR 126B in Q2’24 but still came in lower than the previous two quarters. Of this, almost half, or PKR 62.5B, came from fee, commission and brokerage, jumping 14.4% over the same period of 2023.

Net income dips

Read: The skewed fundamentals of microfinance

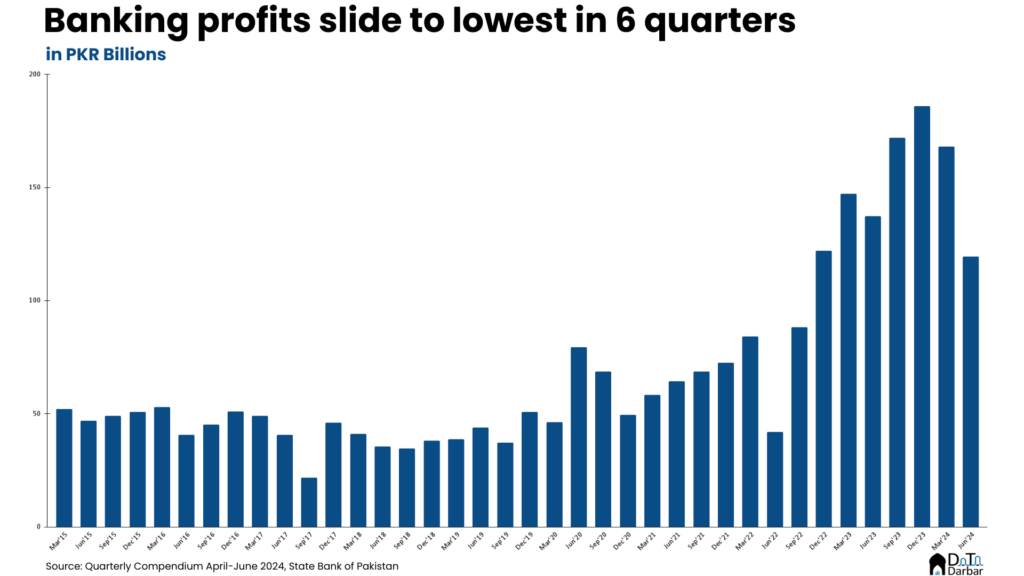

Overall, scheduled banks in Pakistan posted profit after tax of PKR 119.4B. Not only does this represent a decrease of 13% YoY and 29% QoQ, the net income is actually the lowest since Q3’22. Obviously, that’s not a great time horizon to begin with since the last couple of years have been a bit too easy for banks even by their own standards. Consequently, the net margin of 20.7% was the second lowest in five and a half years.

While banking has always been a lucrative business, the last few years were rather extreme: assets, liabilities and profits increased like never before. But most of this growth is quite hollow. For now, let’s skip the arguments about the lack of credit issuance, innovation or any regards for the customer. Those have never been the industry’s goals anyway.

Hollow growth

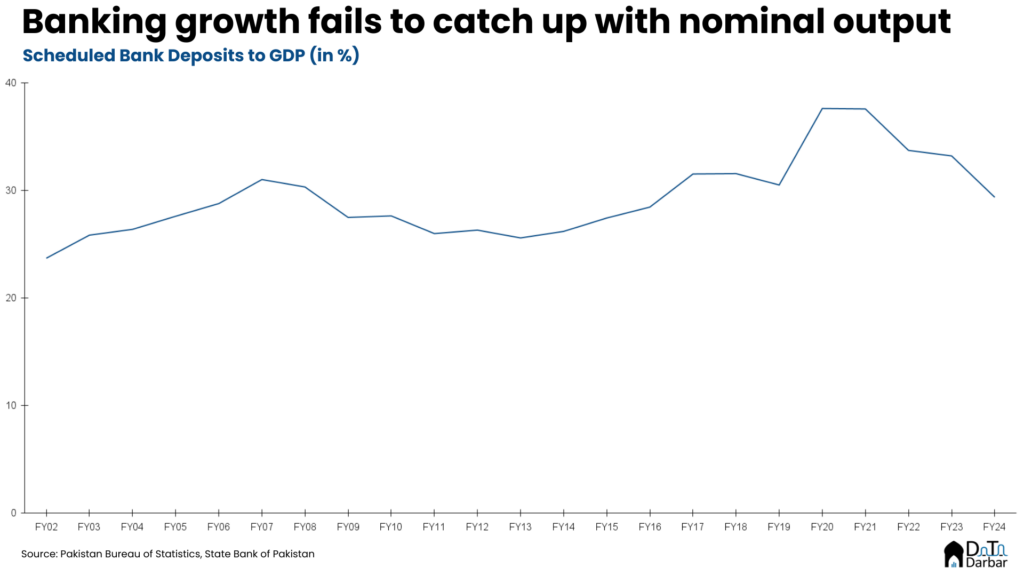

Instead, focus on how deposits held by scheduled banks in Pakistan as a percentage of gross domestic product fell to 29.4% by FY24 — the lowest since FY16 and 8.25pps below compared to the peak of 37.6% seen in FY20. During this period, the industry has constantly bragged about mobilizing new funds from customers at conferences and social media, yet here we stand.

To contextualize our position vis-a-vis others, let’s look at this metric from 2021, the latest year for which World Bank data is available. Where Pakistan stood at 32pc, Egypt was miles ahead at 80.8pc and Bangladesh 41pc, despite its slide. None of it is surprising though, because anyone who has ever tried opening an account — whether personal or corporate — knows how you have to practically beg the staff to extend the courtesy of taking your funds in. It’s just that those making decisions have probably not bothered to visit a branch in decades. At least not without the protocol of a brown sahab.

A shorter version of this article first appeared in Dawn.