In Pakistan, budget discussions typically revolve around a familiar triad: austerity measures, increased taxes on the salaried class, or defense spending. These headlines often overlook a critical component of the country’s long-term economic growth: development expenditure. In this policy brief series, we look at how far Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) budgets have fallen behind.

At the time of the speech, the FY25 budget proposed to increase the federal PSDP to a ‘record’ PKR 1.4T. This consists of the government’s planned expenditure on infrastructure and development projects in the public domain. These include the energy, transportation, health, and education sectors.

PSDP numbers in context

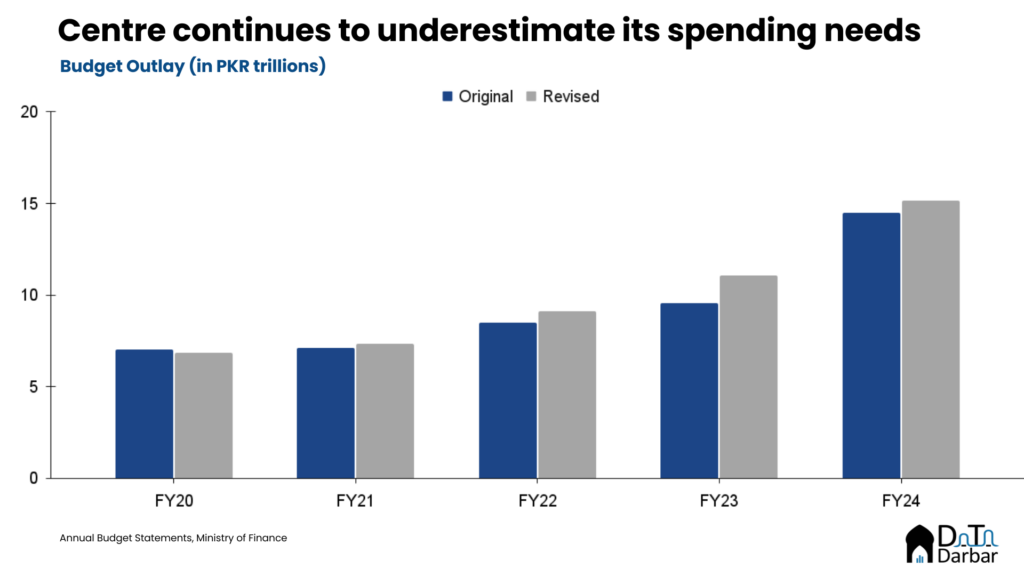

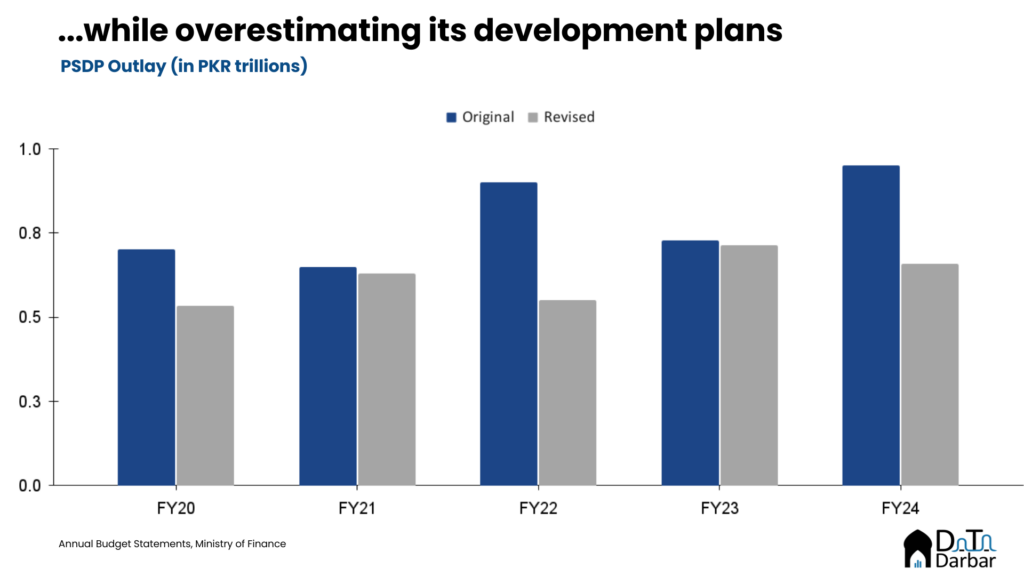

While the proposed amount is certainly the highest ever, it’s important to contextualize the numbers. The respective governments have a rich history of backtracking on their promises to the people as when their pockets are tight, development is the first line item whose expenditure is slashed even as the overall outlay is increased. In three of the last ten years, the center has revised its total expenditure upwards, with the adjustment on average higher by 3.9%.

On the other hand, PSDP has been cut all but once in the last decade. More importantly, the size of the adjustment is much sharper as the revised outlay has declined by 17.3% on average between FY15 and FY24. In other words, development spending is arguably the most expendable head for the center and reduced at the first sign of fiscal distress.

The upcoming year is unlikely to be any indifferent. Barely two weeks after the FY25 original budget, media reports suggest that PSDP has been slashed by PKR 250B to PKR 1.15T. This is just the beginning and as months progress, you can expect further revisions. Particularly when the time comes for the International Monetary Fund staff reviews.

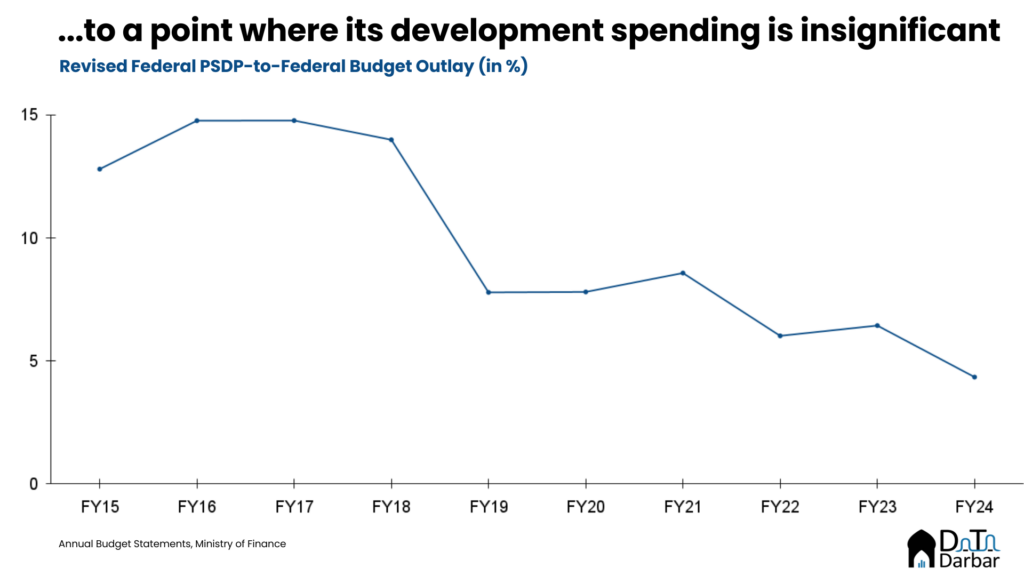

With continuous revisions, we have reached a point where the center merely allocates 4.4% of its budget towards PSDP. Less than a decade ago, during FY16, this ratio stood at 14.8%. The biggest reason behind the decline in the share of PSDP is the ballooning interest payments of PKR 9.8T, expected to eat 51.8% of the entire budget outlay in FY25. The sum is 4.6x the next biggest component i.e. defense and now makes up more than three-fourths of all the tax collection by the Federal Board of Revenue.

A real (value) tragedy

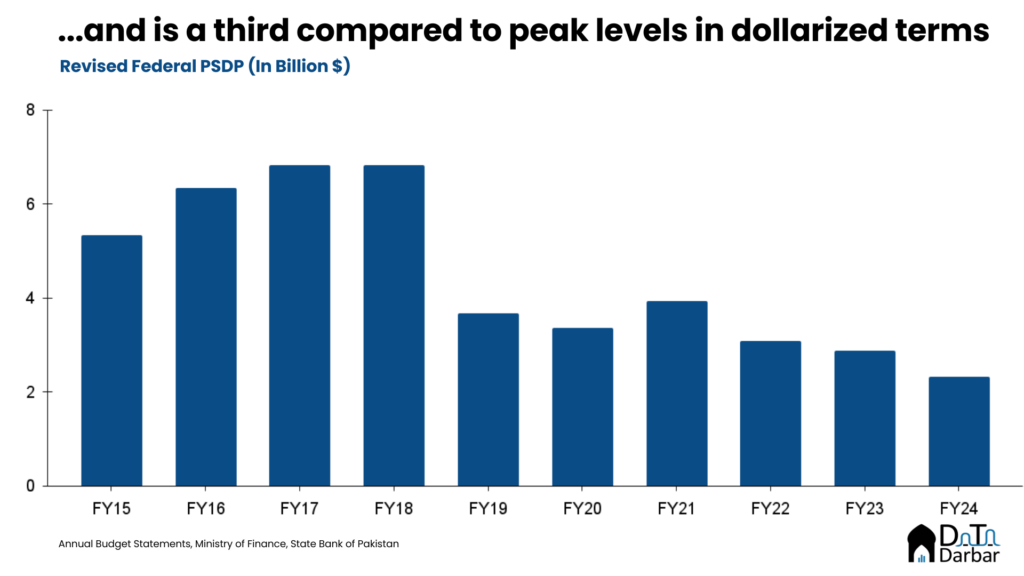

Another way to look at this stagnation, or decline, is that the revised federal PSDP of PKR 659B in FY24 was less than the corresponding figure in FY16. This is in nominal terms by the way: the actual decrease in development spending would be far steeper considering that since then, price levels have increased by a cumulative 156%.

Considering that a significant component of PSDP goes towards infrastructure projects, with raw materials dependent on imports, it makes sense to look at the dollarized values. In FY24, the revised federal expenditure on development was just $2.3B, not only down 19.2% YoY but less than half of where it stood a decade ago.

Provinces to the rescue?

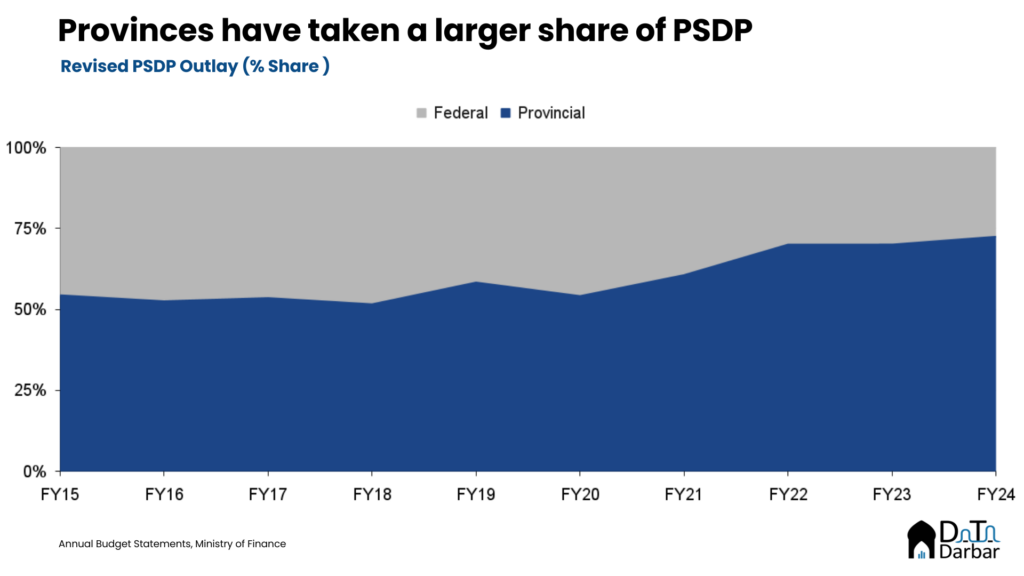

Now obviously, one can argue that federal PSDP is just one part of the equation. After the 18th amendment, it’s the provinces who are not only primarily responsible for development but also continue to allocate a significant portion of their respective budgets to it. The distribution of National PSDP between the center and provinces is important to note as we try to look at the complete picture.

The share of provinces in the national PSDP budget has been increasing of late, reaching a high of 72.5%, or PKR 1.7T, in the outgoing fiscal year. A decade ago, this split was quite close to half. Unlike the center, the provinces have even significantly revised their development budgets upwards on several occasions.

Federal PSDP focuses on infrastructure and strategic initiatives, while the provincial PSDP addresses needs in sectors like education, health, and agriculture. It is up to speculation whether this reflects a change in development spending strategy, decentralization or simply the appeasement of political alliances.

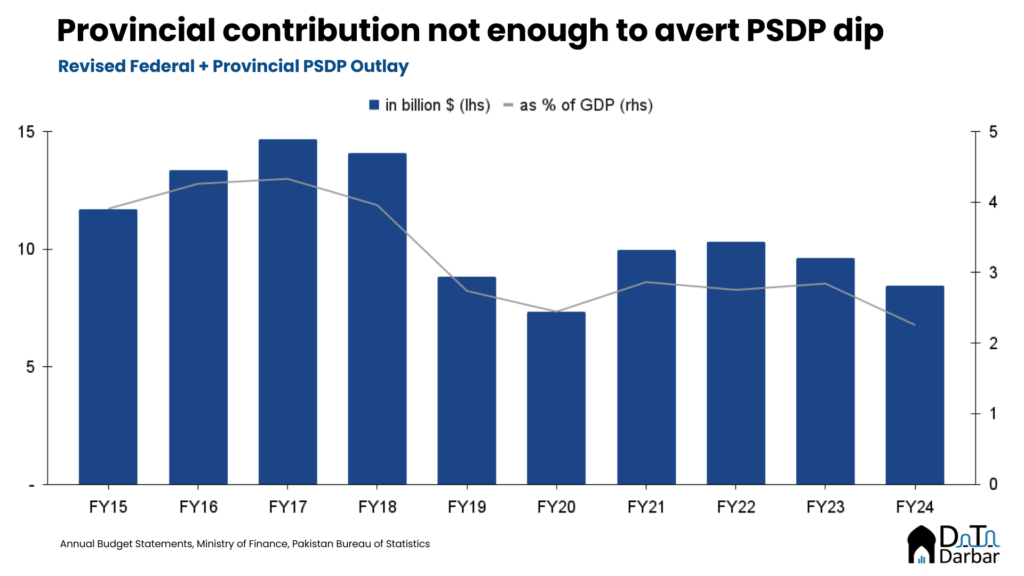

Thanks to the provinces, the national PSDP has managed to increase, reaching PKR 2.4T for FY24. However, Pakistan’s development expenditure as a percentage of the GDP fell to just 2.3%, compared to 3.9% in FY15. In dollarized terms, the decline looks sharper as the outlay stood at $8.4B, significantly below the $14.7B figure seen in FY17.

The reasons are known to everyone: the rupee’s devaluation has hit the dollarized value of PSDP budgets hard, and the twin deficits have ensured the local currency doesn’t experience any stability. In such an environment, it can be extremely difficult, especially amid pressure from the International Monetary Fund, to keep up with development needs. But how much longer can we afford to ignore them? And what comes next: provincial spending on health and education, or cash transfers to the poorest?