If you too are a regular short-format video consumer, thanks to a jellyfish attention span, chances are the big tech algorithms are showing you clips from Shark Tank India. After a successful edition last year, Sony Entertainment is back with another edition of the Indian version of the famous Shark Tank show, where entrepreneurs pitch their businesses to major executives and investors, raising money on the spot.

While BharatPe’s former MD Ashneer Grover’s absence has meant fewer memes, the show has continued to deliver on its key promise: encouraging a culture of entrepreneurship in the country. It has managed to bring people from diverse backgrounds — from small villages trying to streamline farming to the usual IIT, IIM, and consulting archetypes. The common theme is their passion to build something. Add to it the usual masala and drama so characteristic of reality television, especially Indian.

Shark Tank India in Numbers

But did Shark Tank India deliver in creating more deal flow? Using crowdsourced lists from Wikipedia and Kaggle, we analyzed the data. During the first season, 67 deals worth ₹425M were closed in total against a cumulative ask of ₹3.75B. In dollar terms, that’s $5.54M as of the exchange rate at the time (January 31, 2022). [Note: some of the episodes didn’t telecast so no way of verifying them].

For context, the average ticket size of a seed deal in India last year was $2.1M. Mind you, many of the startups pitching had serious numbers — with revenues running into ₹100M+ a year in certain cases. In comparison, the mean investment size here was just 6.35M. Similarly, while pitching, founders on average offered just 4.59% of the equity, while the mean dilution of closed deals was 15.89%.

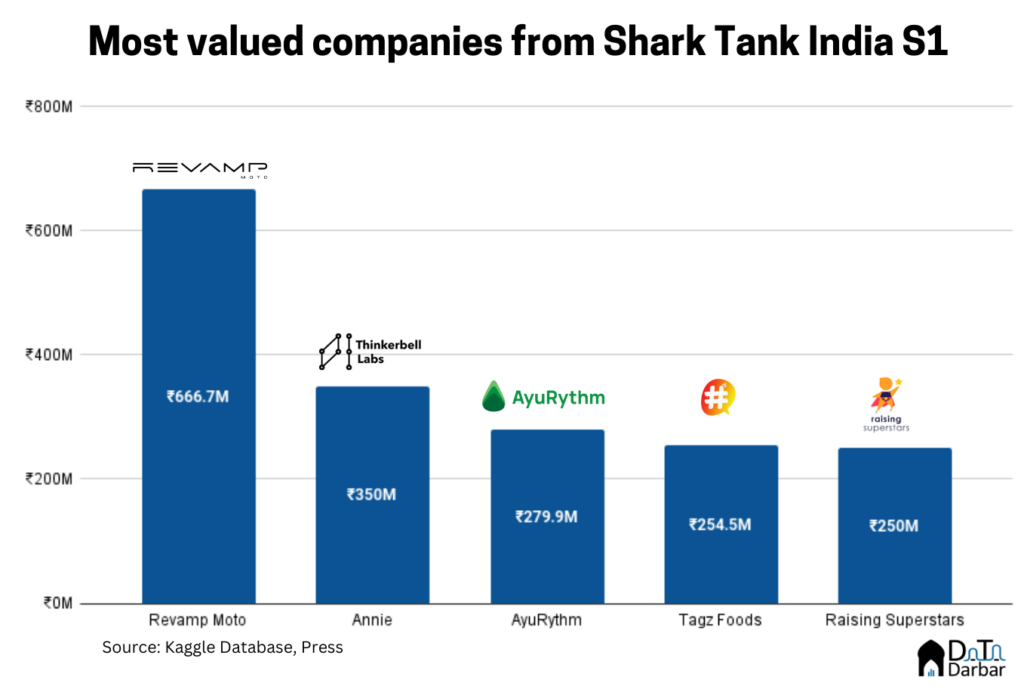

Meanwhile, edtech Aas Vidyalaya raised the biggest round of ₹15M against 15% of its equity. Revamp Moto, an EV scooter maker, got the highest valuation of ₹666.7M by giving up only 1.5% of the stake. Sector-wise, most of the money (₹111.5M) went to food and beverage startups, with beauty and fashion far behind at ₹55M.

What can Pakistani founders learn from it?

If you have been following the startup funding trends (in Pakistan or elsewhere), these numbers are obviously odd. For starters, the amount of money on the table is too little. I mean the entire stock of companies cumulatively raised less than what three average seed deals in India could bring in.

But how does it relate to Pakistan? Basically, the emergence of venture capital over the past few years has skewed our expectations of what constitutes a round. The “biggest-ever” pre-seed and seed deals have pushed the bar for fundraising a little too high.

This is primarily because fundraising has been equated with VC with all other capital options almost dismissed. As a founder, the asset class is obviously appealing: you can potentially get billions of rupees versus millions, against possibly lower equity. Plus, you can draw a much better salary. But that’s a pretty simplistic, and myopic, way to look at things.

First of all, do you really need that big a round? You might be thinking, well, the more the merrier. But with great money comes greater responsibility – meaning higher targets and benchmarks to beat. To achieve them, you exhaust funds by subsidizing growth, and then start bringing in new investors. Rinse and repeat. Pull out the plug, and the customers will run away.

Anyway, we digress. The key point here is how bigger rounds distort the expectations between private and public markets, further widening the gulf. So if you are raising $10M or more, you are essentially ruling out the possibility of existing via listing. Take the case of Dalda, which is going to the PSX and seeking PKR 3.3-4.6B ($12.7-17.8M) against 15% equity. This is among the biggest and oldest brands in Pakistan with positive net margins and revenue growth of well over 20%.

This brings us to the second takeaway: how so many companies on the show wouldn’t even fit our restrictive definition of being a “startup”. A lot of them were food and beverage or fashion players, from Kerala’s iconic banana chips to urban streetwear. Instead, they were trying to build brands in their respective categories and using whatever distribution channels available, be it airport shops, Amazon or their own website. Tech was merely one of those channels, not the business itself.

In Pakistan too, there is a dearth of new brands with national reach. And they don’t have to be product-based startups disrupting an industry. Think of your favorite local donut brand or that page from Instagram whose clothes are always sold out. How some capital injection, instead of the biggest-ever Series A, could benefit them in going nationwide? Unfortunately, that avenue has so far been missing.