The financial results for the third quarter have started pouring in, and for banks, it’s a bonanza with triple-digits bottomline growth. While the sponsors and senior management may be excited, it’s a cause of concern for the broader economy. After all, the numbers symbolize a broken system where the sovereign can’t keep its house in order and financial institutions fail to do their job. The biggest casualty of this collective incompetence is borne by the small and medium enterprises (SME) of the country. We have heard this story countless times before: of how SMEs in Pakistan, despite making up 90% of all businesses and employing 30% of the labour force, are not realising their potential. The reason is simple: they lack access to credit because, you know, banks here don’t do any funny business. Unless of course, you are a certain oil marketing company.

Revewing SME credit numbers

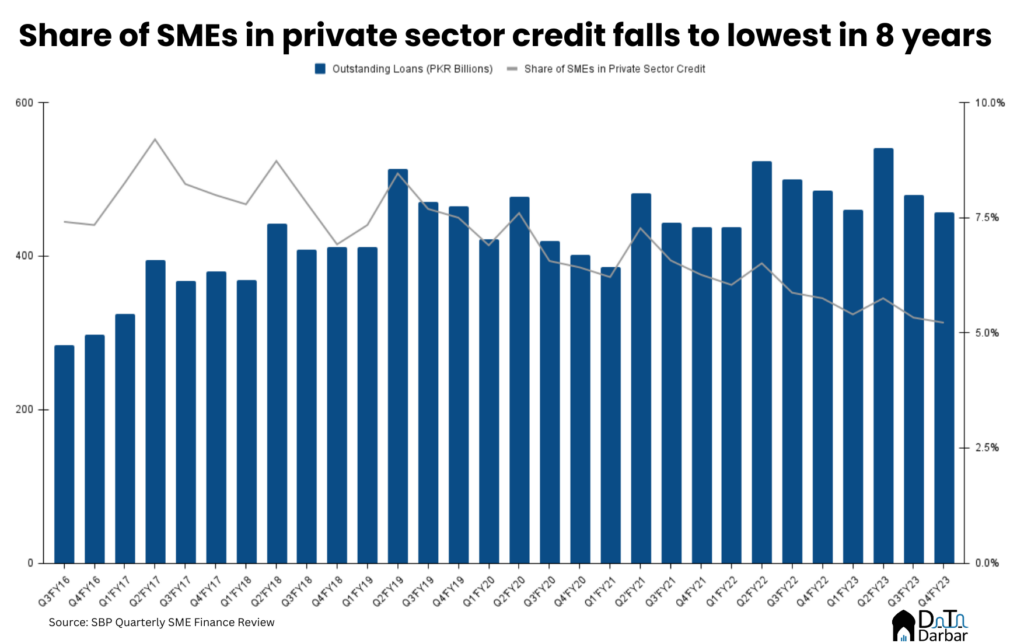

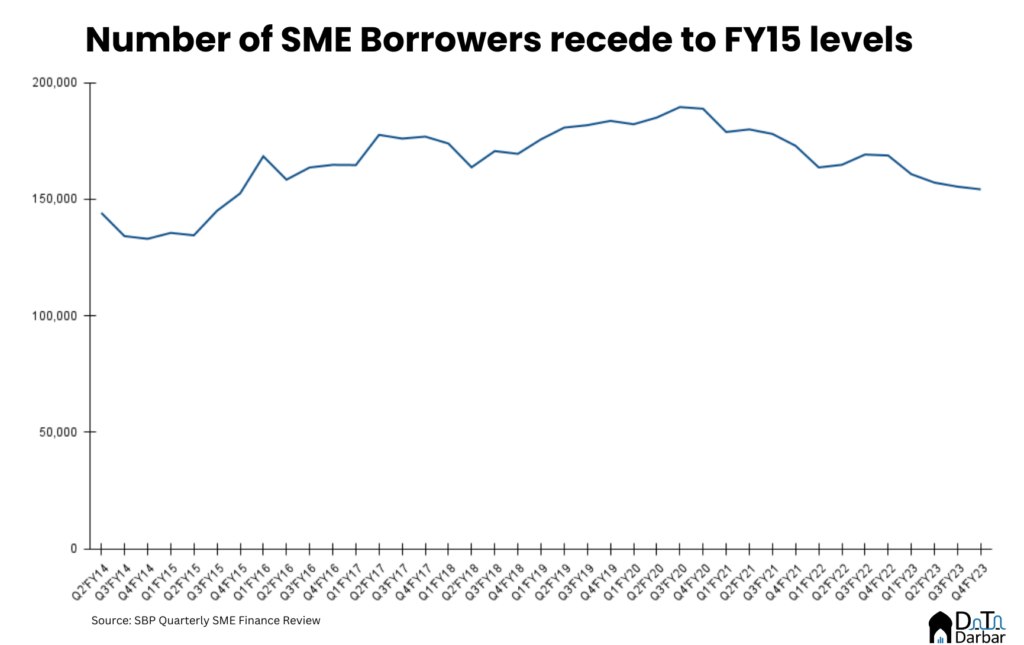

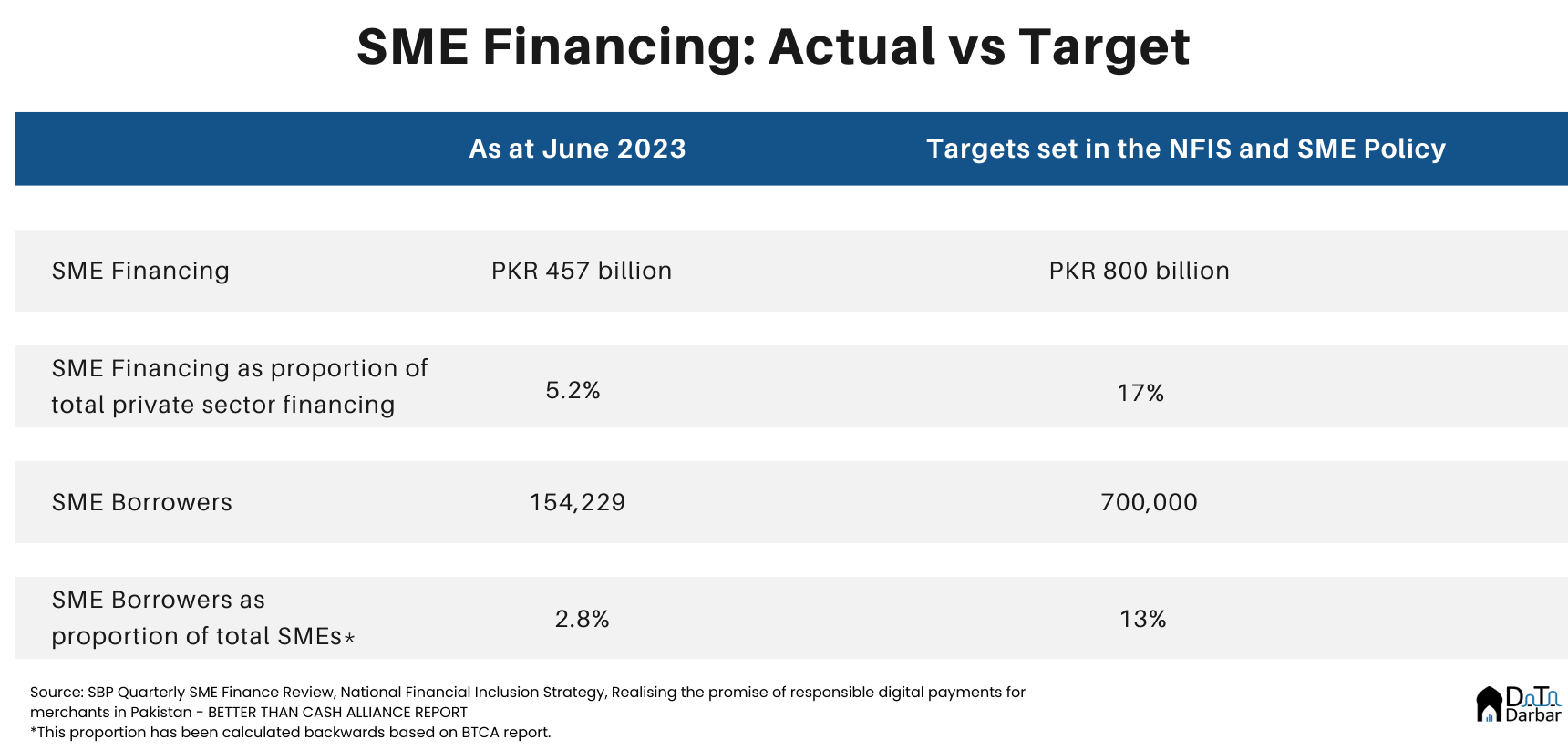

As of June end, the total outstanding SME financing through financial institutions stood at PKR 457.1B. This is 5.7% down compared to the same period last year and 4.6% over the preceding quarter, according to the SBP. Meanwhile, the number of borrowers reached 154,229 — the lowest since June 2015 levels.

Sector-wise, 40.17% of the SME credit1 went to manufacturing, which in comparison to the non-SME is not that concentrated. In relative terms, wholesale and retail trade performed the best with PKR 166.1B — accounting for 54.46% of the category financing and 31.93% of the SME total.

Similarly, the share of SME in private sector credit — which itself is a problem — fell to just 5.22% by FY23. This is the worst since at least June 2015. Now obviously, given the recent political and economic environment, it’s not surprising to see a decline in numbers. But this is a far older problem, one we have barely done anything to solve.

According to the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys, 40.9% of firms in Pakistan are fully and 15.2% are partially credit constrained. This is considerably worse than the South Asian average of 17.1% and 17.7%, respectively. In most indicators, we lag behind. Sample this: only 2.1% of the local businesses in the sample had a bank loan or line of credit, compared to the region's 23.7%.

Do the incentives ever work?

Over the years, there have been multiple attempts to address this problem and the regulator has talked about it more times than there are SME borrowers. But nothing seems to have come out of it. In its recent report, the Better than Cash Alliance produced a pretty telling table. As of December 2021, total outstanding SME credit stood at PKR 460B, as against the PKR 800B target set by the National Financial Inclusion Strategy of 2015.

Read: How women (don't) borrow

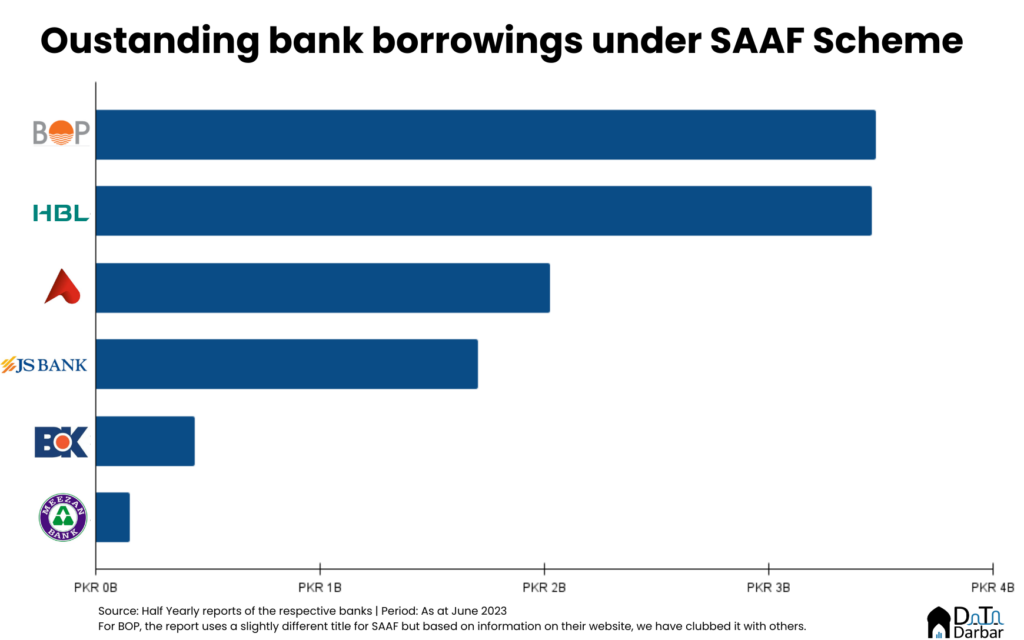

More recently in 2021, when the then government and its cheerleaders were still selling the growth story, the regulator introduced SME Asaan Finance Scheme (SAAF). Under this program, small businesses were to be given uncollateralized loans with capped pricing and the federal government guaranteeing part of the credit risk. As of June end, the total bank borrowings through this scheme stood at PKR 11.25B or only 0.64% of the industry’s borrowings under all refinancing facilities.

The SME finance pet projects

The subsequent unraveling of macroeconomic indicators and the change in government unsurprisingly impacted the uptake of SAAF, which again is a recurring feature of every policy in the country. For SMEs, this is perhaps best exemplified by the name-shifting entrepreneurship initiatives by Pakistani prime ministers.

For example, Nawaz Sharif launched the PM Youth Business Loan Scheme, under which cumulative disbursements worth PKR 26.76B reached 26,679 beneficiaries as of June 2019. Then, the government changed and there was apparently a new initiative: the much-hyped Kamyab Jawan Programme.

Herein, 25,825 disbursements of PKR 41.1B were made by March 2022. It continued until December of the same year, reaching figures of 29,990 and PKR 51.9B. But then it was time for a re-rebranding as Shehbaz Sharif revamped and introduced the Prime Minister’s Youth Business and Agriculture Loan Scheme. It’s all in the name. Under this initiative, cumulative loans reached 29,351 and amount PKR 14.9B by June.

Now, both the guys have departed and may not be back again for premiership, albeit for entirely different reasons. And with them, these loan schemes will fizzle out, only to return with new nomenclature. What will remain constant is the lack of financing that Pakistani SMEs access while an incompetent sovereign continues to scoop all the possible loans.

Don’t worry though, the regulator may launch a new policy document and the bankers will certainly try to score a few brownie points at conferences talking about the lopsided state of credit. It will be business as usual, where everyone walks away with something, except for the SMEs.

A shorter version of this article first appeared in Dawn.

- Sector-wise data is taken from SBPs' Loans to private sector business by type of finance, which differs from Quarterly SME Finance Review ↩︎

Insightful but this research or report should be having Fintechs and their impact in SME Lending.