Over the last year, venture capital has undergone a sharp correction, with funding amounts all but evaporating in Pakistan. Similarly, valuations have started declining, meaning that some start-ups are worth a fraction of what they were previously. It also means that for the same dollar value of investment, founders now need to give up more equity.

However, a drop in valuation often leads to a messy capitalization structure. Founders are then left with two choices; pack up or dilute the existing investors such that they have to mark down their ownership in the venture significantly. In both cases, the existing VCs (provided they are not participating in the new round) will lose most, if not all, of their existing investment.

The graphic shows how difficult it is for startups to maintain existing valuations and why many resort to down rounds. Note that the figures are hypothetical due to a dearth of data but this is what the market is signaling.

Put your money where your equity is

According to Carta, almost 20% of all deals in Q2-2023 were down rounds. Meaning every one in five companies raised money lower than its previous valuations. This is the second-highest quarterly figure in the last five years.

This has led to reports that some founders are resorting to ‘Pay to Play’. In very simple terms (and how it actually plays out can vary a lot), this is generally when founders, faced with a significant down round, give an ultimatum to existing investors that either they invest, or they face disproportional dilution of ownership in the start-up. It’s a somewhat controversial thing with some VCs viewing this as blackmail, though many understand the necessity of the ultimatum.

Earlier this year, Silicon Valley heavyweight Sequoia Capital declined to participate in a “pay-2-play” financing proposed by one of its portfolio companies. Faced with the decision to either reinvest or suffer a level of dilution that would largely eliminate its existing investment, Sequoia walked away, and its representative resigned from the company’s board.

Pay or go away: The Pay-to-Play Power Play

This represents a common “pay-2-play” approach to punish existing investors who fail to take up their pro rata share of a new financing round by compelling the conversion of some or all of their prior investment into either common shares or a newly created class of preferred shares having reduced economic entitlements. Alternatively, only a portion of the investor’s existing shares may be converted, in a manner that correlates to the proportionate participation in the new round. There’s a variety of ways this can be structured and the level of aggression can also vary widely.

These conversations are not only very uncomfortable but also incredibly complex. Getting the transaction approved by the board may be difficult. And it gets more complicated when these rounds are insider-led, which could lead to a conflict within the board as the new financers would want a structure that sufficiently rewards them for the risk they undertook, and that structure, more often than not, would come at the detriment of the existing investors sitting at the board.

Another conflict arises with the existing VCs, who would have to mark down their existing investments. These VCs generally rely on the paper value of their portfolio companies to raise additional funds. And down rounds would impair their ability to do so. The existing management would also need their option pool to be refreshed. Otherwise, their ESOPs (already a questionable asset class) would likely be perceived as worthless.

There are a number of issues that we have not discussed, that may or may not be unique to that venture.

What is the commercial case for pay-2-play?

“Pay to Play” is warranted when the founders genuinely believe in an alternate business model. One that can find them success, provided there is more capital (runway). The founders also understand the need to take a significant down round in order to raise again. Hence the only route to survival is dilution for the existing investors. This approach is probably going to make sense for startups pivoting into asset-light models.

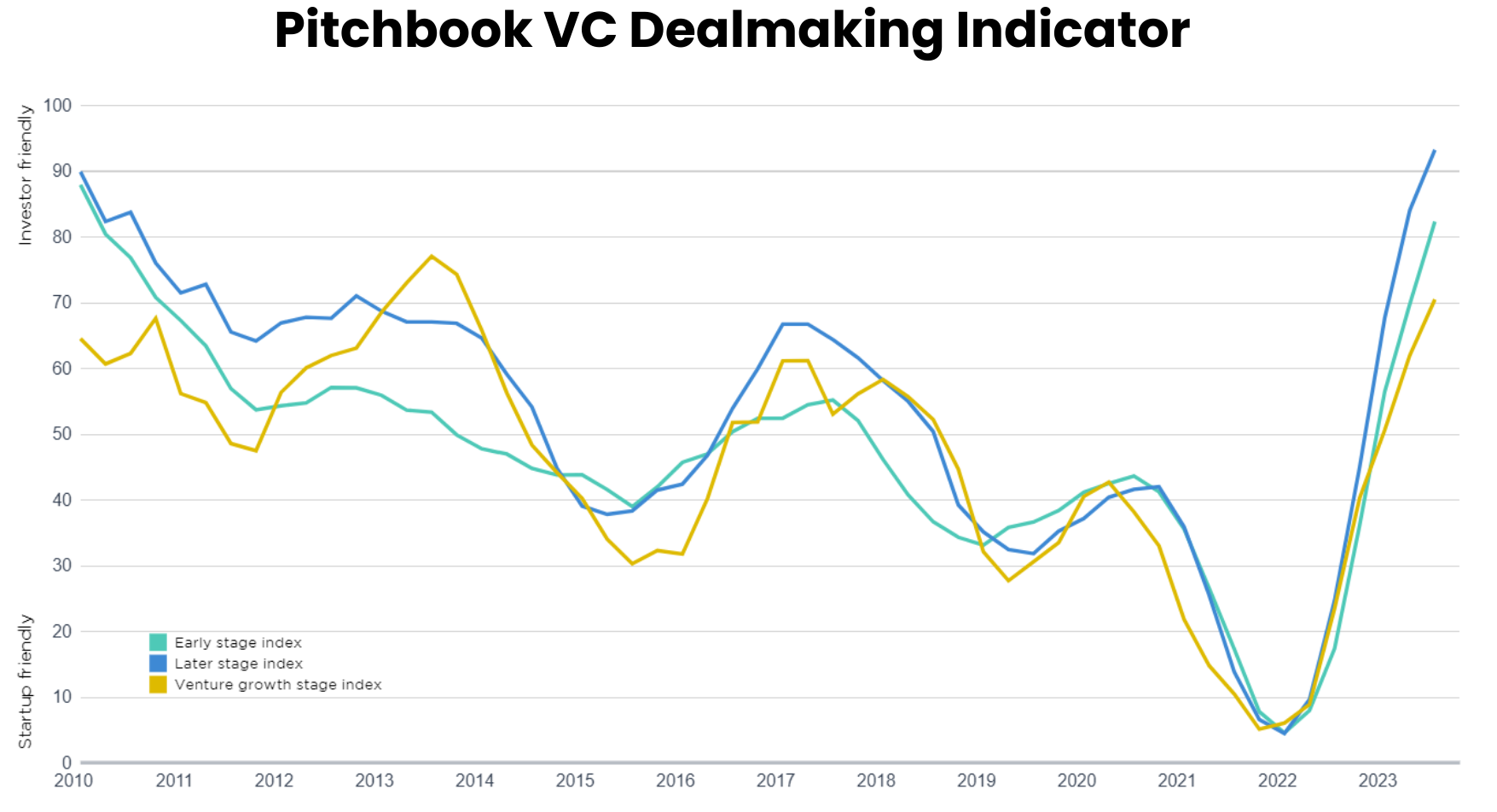

For companies in MENAP, this will be tricky given that VC is a new asset class with constrained capital supply. According to Pitchbook’s VC Dealmaking Indicator, transactions are becoming extremely investor-friendly and the balance of power moving away from startups. But its exercise in the region ultimately depends on:

- If the financing documents allow this to take place

- If they don’t, the VCs need to consent to this.

In the recent past, we have actually seen a few startups going bust because the investors bailed out so pay-2-play provisions can bring in some form of accountability and tip the scale in favor of founders.