Whenever a foreigner asks me “what do you guys do for fun in Pakistan?” I instantly reply “we eat”. In fact, for urban middle-class families, eating is fast becoming one of the only recreational activity in our ever-expanding cities. But surprisingly for a food-crazy nation, we don’t have too many online food platforms guiding us on what and where to eat, let alone a local one. But enter Eat Mubarak, there might be a home-grown one.

Eat Mubarak is a food discovery, directory, and delivery startup that wants to be a one-stop shop for all your food cravings. A Pakistani Zomato, if you will. How does it work? Pretty much like any other food application: Download the app, enter your location and explore all that’s near you, check their menus, ratings, order right from the app and pay through local mobile wallets or cash.

With a select few restaurants, you can track your order too, just like you track your ride in ride-hailing services. Not only that, they are integrating with apps of local startups/banks so you can access it without even downloading Eat Mubarak. Currently, they have around 1,400 outlets to choose from and order from.

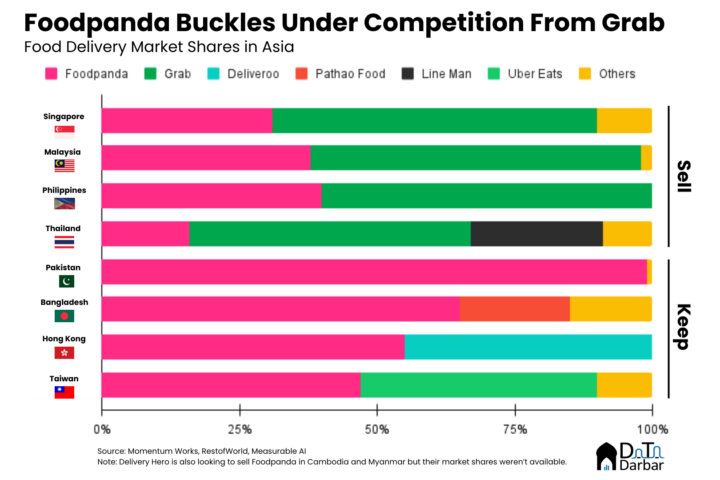

But any talk of food tech takes us to Foodpanda — A Germany-based global giant — which has traditionally acquired local players to gain ground and expand its network. How exactly does Eat Mubarak plan to navigate through when a Goliath, often known for its notoriety, is aggressively trying to capture the market?

“Globally there are around four big players in the industry. India has Zomato, Foodpanda, UberEats, and Swiggy all at the same time while we have only one. The market is too big to be effectively catered by one company,” says Eat Mubarak CEO Syed Sair Ali.

In the developed markets, food apps work a bit differently: they serve as a portal offering both visibility and delivery to local restaurants who (mostly) can’t afford the tech or logistics. But when it comes to Pakistan, most of the local eateries already have their own riders so they don’t usually outsource delivery. As for visibility, there is Foodpanda. What exactly is the utility of Eat Mubarak then?

“The small food joints in question often don’t have the money to invest in tech which is where we come in. Foodpanda, on the other hand, is limited to just ordering while we work on directory and discovery as well. We are also building our own fleet — currently of 100 riders — and are actively trying to get restaurants completely outsource their delivery needs to us, which again is something Foodpanda has shied away from,” Ali explains.

Eat Mubarak was officially launched this September when two entrepreneurs at completely different stages of their lives joined hands. Yusuf Jan — Pakistani American businessman and Ali, who was running a venue booking portal in Pakistan.

“The bookings industry in Pakistan is in the early stages so the work was a bit slow-paced. Food business, on the other hand, has matured here so it was more challenging and rewarding,” says Ali, recalling the switch.

Initial money was put in by Jan but now the startup is going to raise seed money, with details yet to be announced. As for the revenue streams, the startup has two: a commission on vendors for every order received by Eat Mubarak app, plus a fixed delivery fee charged to restaurants who rely on their logistics.

On why the app has received a handful of bad reviews on Playstore, particularly those relating to payment reversals, Ali clarifies: “Reversals depend on payment channels and not us, and since we work with local partners, most of them didn’t have any prior experience in the food business. As a result, the tech wasn’t too mature but now we are working on instant reversals with Alfa, for example, which would be live in around two weeks.”

But the biggest challenge for Eat Mubarak is not payments or tech. It’s logistics. And how exactly do they plan to overcome it? “We are working on a hub-and-spoke model which basically means we will have riders waiting on standby around the major food hubs. That would speed up the delivery timing plus the riders would know the locality inside out. We have spotted 200 spots across the three cities and already have a few live, for example around Sindhi Muslim and DHA,” says Ali.

While currently operating in Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, Ali has much loftier ambitions. “Globally, there is no Halal food ordering app, which is insane given how big the market is. There are apps like Zabiha which help you locate Halal restaurants but none to get your food delivered. So we are looking to capture that market. In fact, we just recently hired an ex-Deliveroo executive as our international growth lead in the UK to get restaurants on board and would soon be pursuing our international plans much more aggressively,” he tells Dawn.