It’s been months since I deleted Twitter. There was just too much hassle because of the big brother’s throttling of internet and VPNs, and all for what? Techbros’ mental models and crypto bots dominating the feed? But there are days when I miss the bird app for one thing: seeing people fight each other from the sidelines.

Most days, LinkedIn is the exact opposite where everyone’s patting each other on the back. It’s an echo chamber of toxic positivity. On rare instances, it can be entertaining though. Yesterday showed a ray of hope for such drama when Swvl’s founder, Mostafa Kandil, called out Menabytes for claiming that the company has shut down its consumer business.

It didn’t really escalate as Menabytes added a clarification soon after and the exchange ended just like that. Quite unlike my own unfortunate experience once upon a time. But there was a common theme here: founder’s words conflicting with the public information available on official channels.

Misleading information or irresponsible media?

While I am not privy to the actual details here, Swvl’s own website doesn’t list consumer operations under its use cases, products or services. In my opinion, that is material and official enough for a story. What you do (and don’t) put on your brand channels holds some value and is not so easily discardable with a comment on social media. Obviously, there’s another argument here: as a press organization, you are supposed to at least ask the concerned party first.

However, this is a very old way of thinking. For better or worse, digital media is very different from legacy outlets. Typically, they don’t have reporters and information is primarily sourced online. So anything available on a brand’s own website is fairplay and doesn’t really require confirming the veracity from the concerned party, unless it’s something very serious. Could Menabytes have asked in this particular case? Yeah, it wouldn’t have hurt. But do they need to get a quote from every company they ever write about? Not possible. Perhaps it is for some publications with ample financial resources but definitely not for a small startup.

Swvl’s turnaround

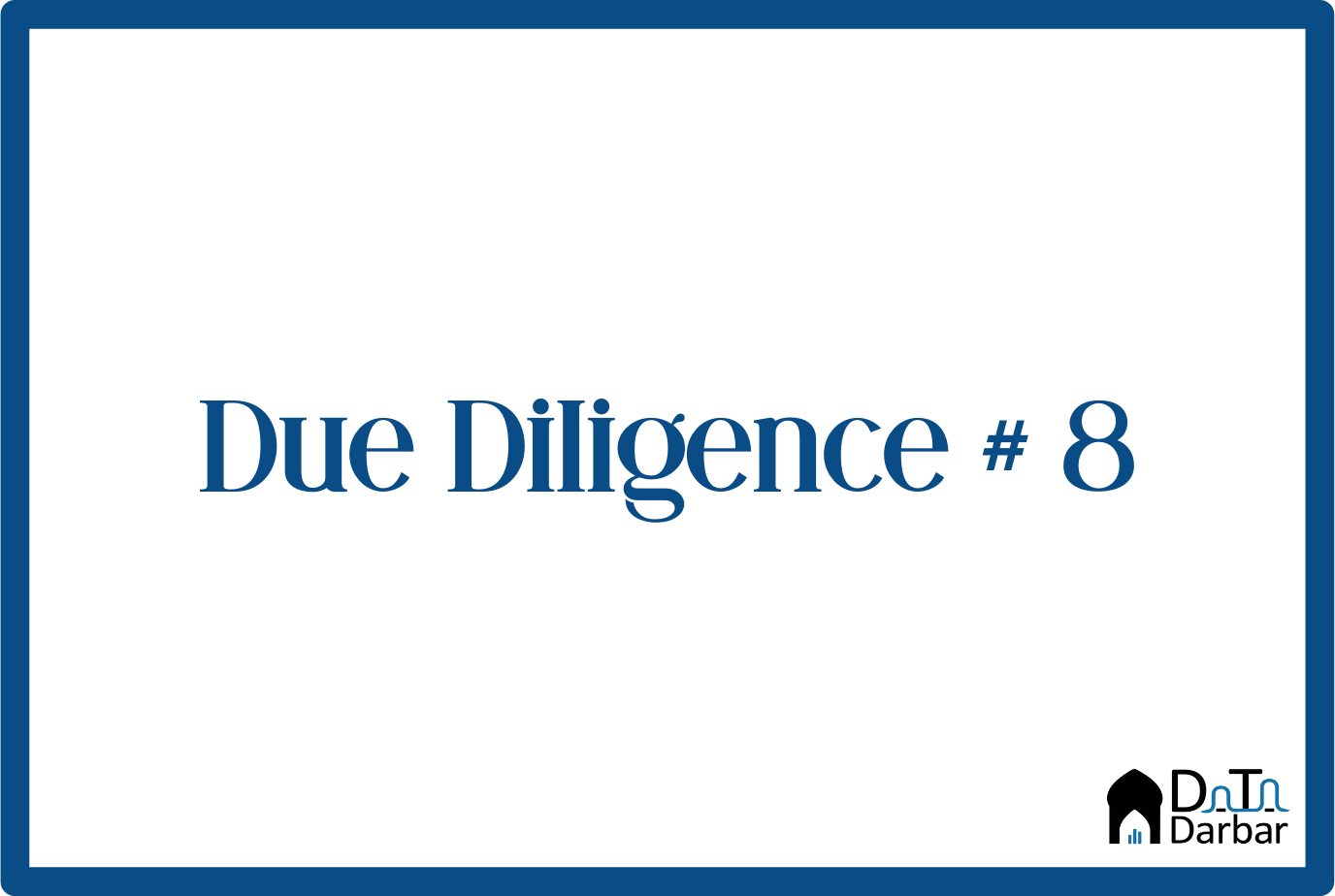

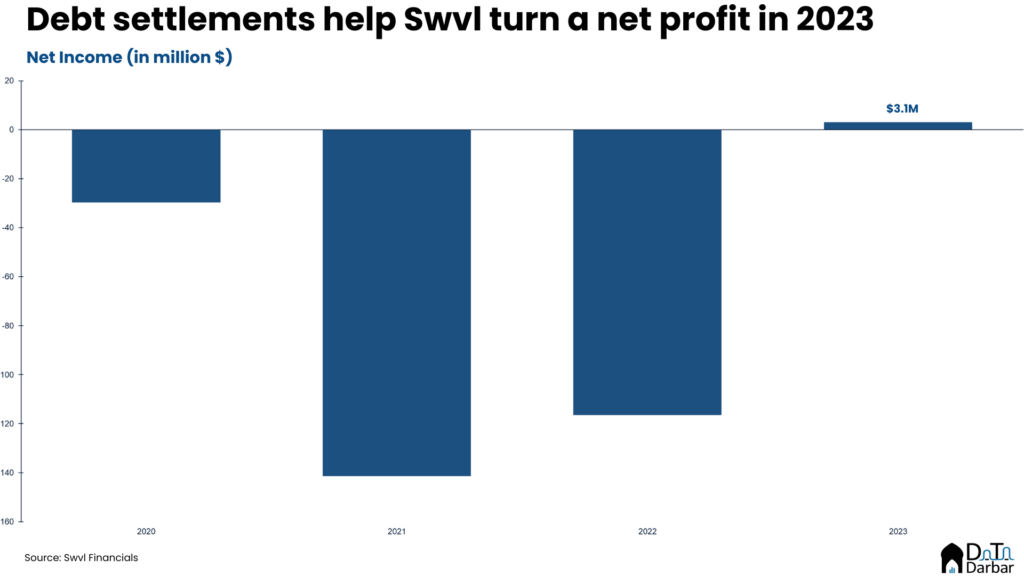

Anyway, whether they serve consumers or investors is besides the point. What really matters is how Swvl has performed and the answer is quite relative. In one sense, the last year was a complete turnaround with the company even posting a net profit of $3.1M in 2023, compared to a loss of almost $101M the year before. Even if the base was awful to start with, this is phenomenal. Since then, it has gotten a few large contracts, most recently one with the Saudi government worth $2.6M annually.

However, the net profitability doesn’t tell the whole story as the figure was helped by creditors giving discounts on loans. This pumped up Swvl’s other income by $18.8M. Don’t get me wrong, that is a great win but it’s not really indicative of underlying operational performance. Even after all the downsizing, the company’s general and administrative expenses were almost 2.5x of the gross profit.

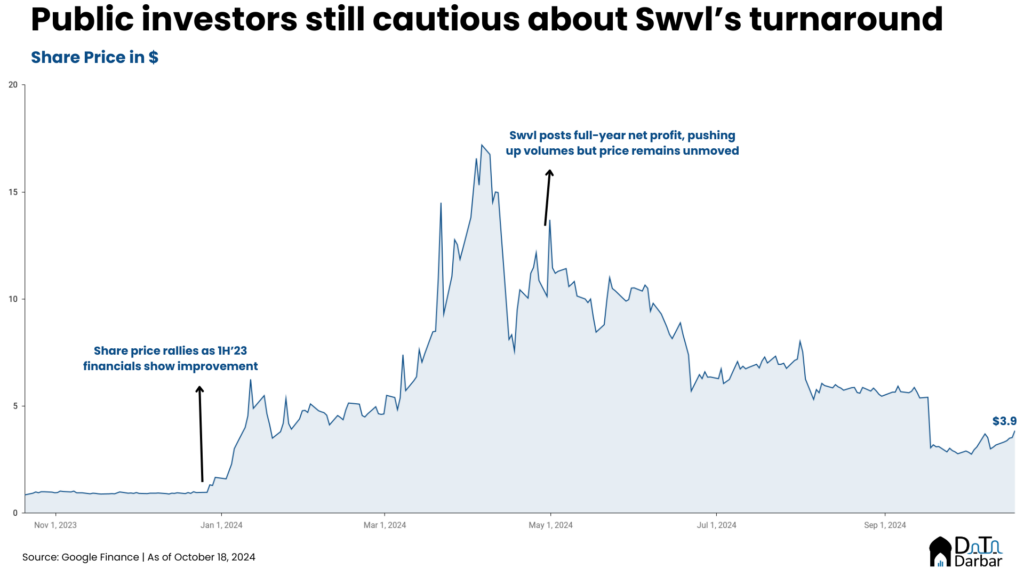

This is probably why despite the turnaround, markets aren’t fully buying into the story yet. There was a rush right after Swvl announced 1H’23 results last December, which saw the price shoot up from around $1 to hover near $5 for the following couple of months. Shortly before the annual report was supposed to come out, the share rallied to as high as $17.2 but is now back to becoming a penny stock at just $3.85 apiece. Which means Swvl’s market capitalization now stands at $246M, a tiny fraction of the billion-dollar valuation it once boasted.

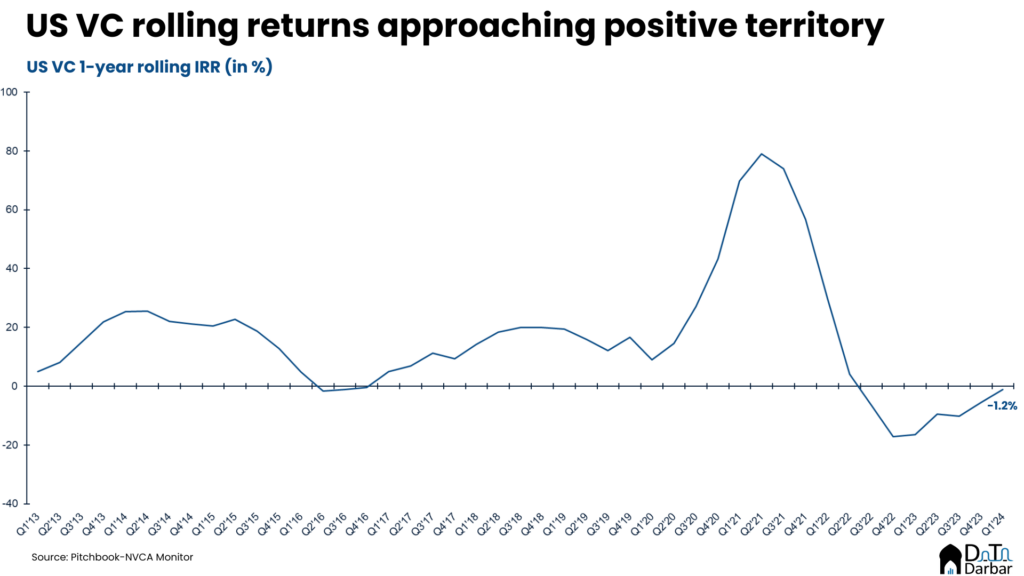

Returns elude VC

Swvl’s not alone here. Many startups over the last few years have seen substantial valuation cuts, either due to new financing rounds, secondaries, or acquisitions. Depending on the metric, those realized or unrealized losses then drag down the returns of their investors. After the Fed hiked the rate in February 2022, the rolling 1-year IRR of US VC turned negative and has remained in the red since Q2’22. However, early signs suggest that returns might enter positive territory soon, having reached -1.2% in Q1’24, per the latest data. Perhaps it’s not an improvement as such and could merely be the effect of a low base?

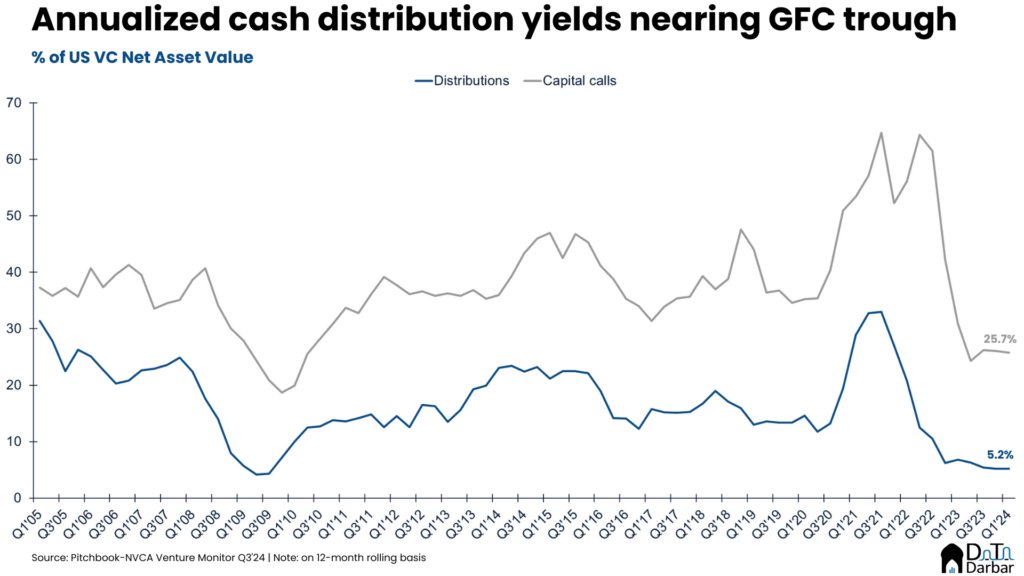

While the IRRs are important in their own right, the bigger question is whether the limited partners are getting their money back? That’s where the picture doesn’t look great. According to Pitchbook, 12-month distribution yield as percentage of net asset value slipped to just 5.2% by March end — approaching the trough of 4.2% seen in the wake of the global financial crisis.

To be fair, it’s not exactly surprising considering how muted exit events have been. In Q3’24, the US recorded a total exit value of $10.4B — just 40% of the historical quarterly median. Other regions are likely in a worse position because, well, they are no match to the scale of American VC. Now that the Fed has cut rates and looks to revive expansionary monetary policy, are there better days ahead for the world of venture? To borrow from Taleb: forecasting is often the last refuge of the charlatan. And I would like to think I am not one.