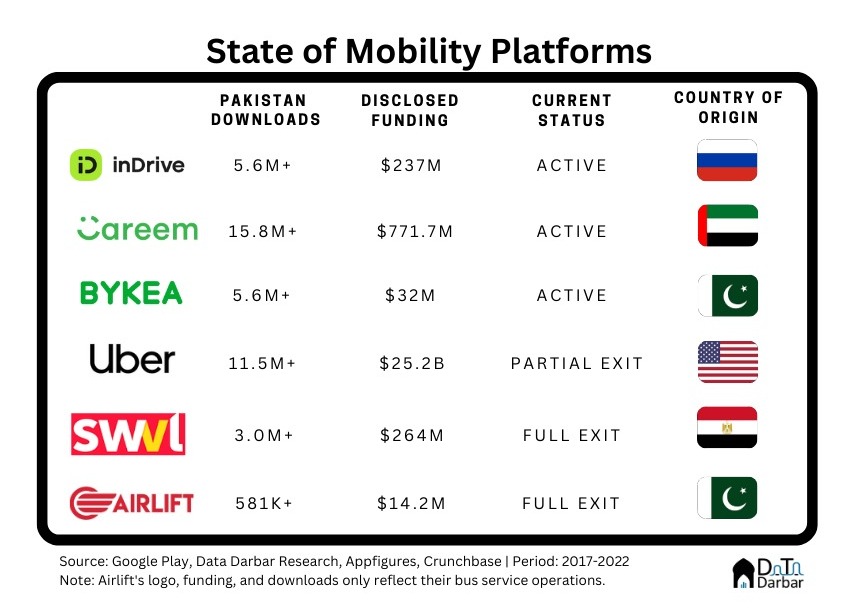

What was life before we had mobility startups to complain about? In a country with crumbling public transport, the daily commute of millions was defined by bumpy roads and constant bargaining and always being late to their destinations. All of this changed, when mobility startups entered the scene.

First came Uber, followed by Careem in 2015-16. Cheaper than driving your own car and a fare superior experience compared to public transport, mobility startups were a Godsend. Initial ride-hailing options only included cars but soon enough the offerings ballooned. From Bykea to Airlift & SWVL, commuters now had the option to choose from bikes to bus routes.

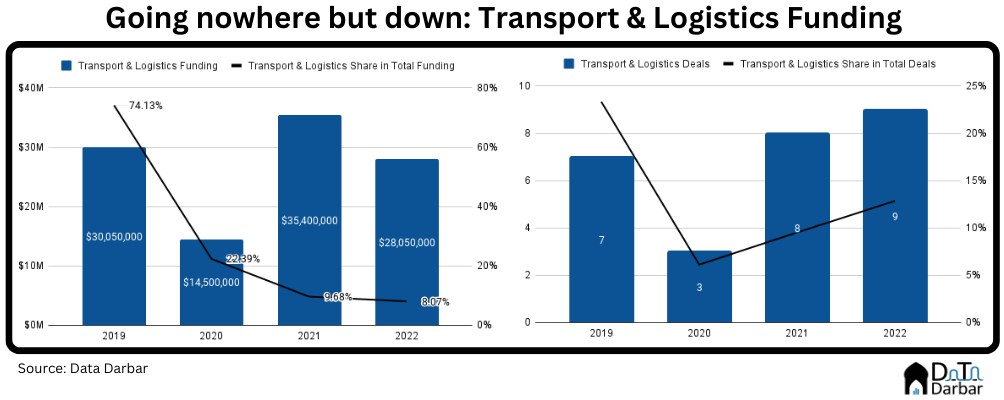

In the absence of a proper public transport infrastructure, mobility startups thrived. The broader transport and logistics was among the first sectors that managed to grab investor interest. For example, of the $30M raised by local startups in 2019, almost three-quarters went to transport and logistics. This was obviously thanks to the big rounds of Airlift, Bykea, and Cheetay.

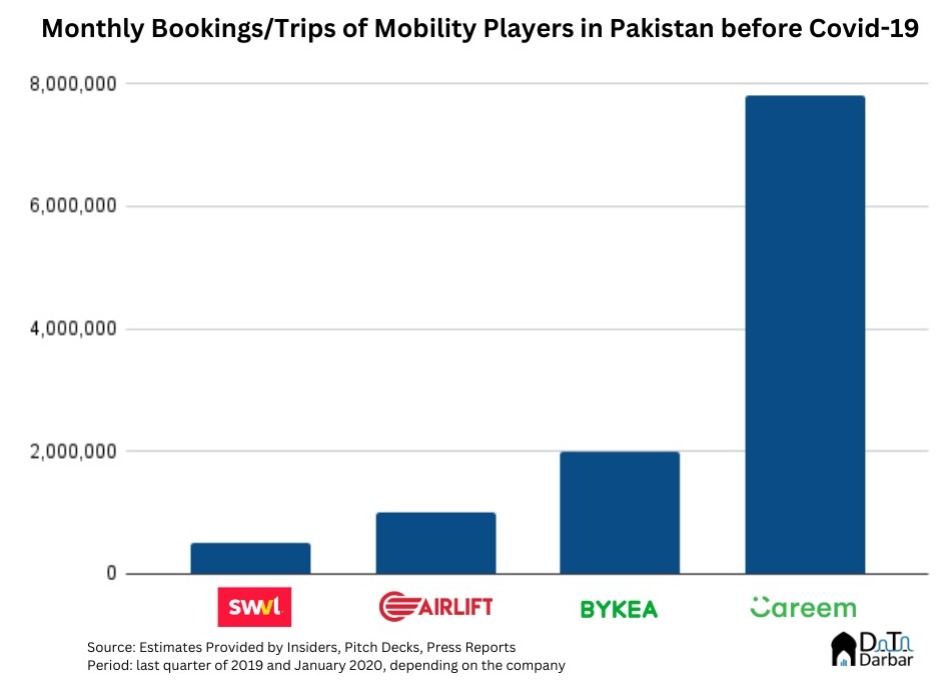

The money translated into serious scale: before Covid, mobility startups showed serious numbers. Overall mobility market based on number of rides were 16-18M at one point. Careem alone did over 100M rides in 2019 while Uber also reportedly hit its daily peak of 450K. Before shutting the bus operations, Airlift too had crossed a million monthly bookings.

Cut to 2022 and only Bykea and Careem stand while all others have pulled out. And they too are barely standing. In 2022, transport and logistics accounted for just 8% of the overall capital. Meanwhile, the number of deals has barely grown in the past four years. As for the major players, Airlift pivoted to q-commerce in early 2020, Swvl pulled out of Pakistan and Uber operates only in Lahore. Those still around are nowhere near the same, both in experience and pricing.

The downturn in mobility is not an isolated to Pakistan but rather part of a broader trend. Ride-hailing, in particular, has lost its lustre and model’s unit economics don’t seem too appealing. Especially in Pakistan, where rupee depreciation and rising vehicle prices have made the business less lucrative to supply, while lack of discounts have compressed demand.

In this piece, we’ll look at the state of four mobility companies in Pakistan: Bykea, Careem, Swvl and InDrive.

Bykea

Bykea’s example demonstrates the obstacles that even a relatively successful mobility start-up faces during its growth stage in this investment climate. The company claims to have grown 5.7x post-pandemic and is reportedly margin positive after paying for marketing and incentives. Yet, they weren’t able to close a targeted $50M Series C and instead settled on a $10M bridge from existing investors. And this takes us back to macroeconomic conditions, where a startup’s own metrics, while highly relevant, have taken a back seat.

Bykea demonstrates how expensive it is for mobility start-ups to expand within Pakistan because they require significant investment to educate customers about the service. And this is especially difficult for businesses in their growth stages — they need large rounds from optimistic VCs.

Careem

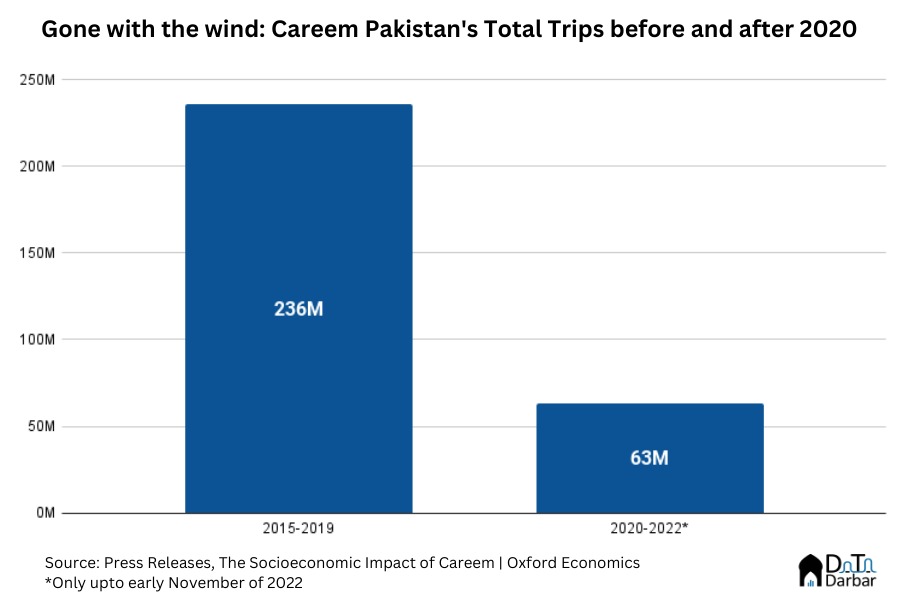

Careem may technically not be a Pakistani company but it changed the local tech ecosystem in ways that no one has since managed. At its peak, the ride-hailing company was doing over eight million trips monthly and launched other services like food delivery, intercity buses, etc. However, since 2020, it has become a shell of its former self, let alone grow.

Of course, Covid-19 drastically hit volumes as rides plunged to 9,500 in April 2020. But that wasn’t the only reason: after Uber’s acquisition, its wings (money) were clipped and Careem could no longer spend like crazy on getting customers. To put into context how bad things are for them, sample this: the company did 236M rides during 2015-2019, with over 100M coming in the last year. Between 2020 and November 2022, that number was just 63M.

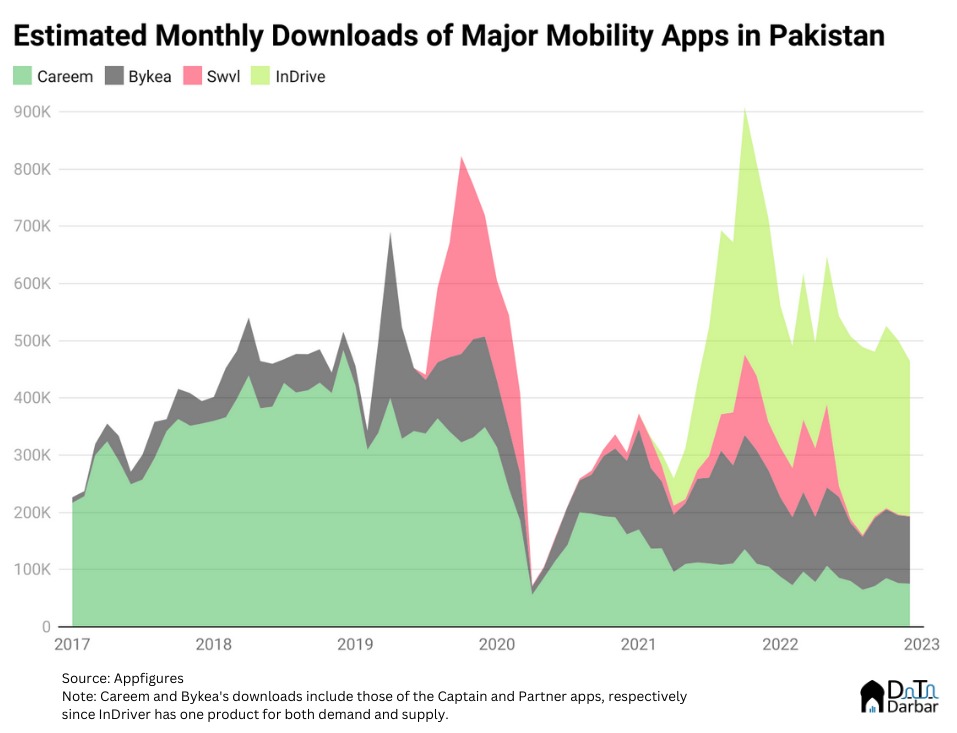

They are now struggling to retain their supply due to dwindling captain numbers, and face intense competition from InDrive. At the same time, the company, like others in the sector, were hit by the changing macros of Pakistan. For example, both car and fuel prices have risen substantially since 2018 while the dollar has depreciated, making transport a particularly difficult area to operate in. Last year, the company announced plans to invest $25M and increased captain incentives but that hasn’t been enough to dissuade demand and supply from hopping to the competitor.

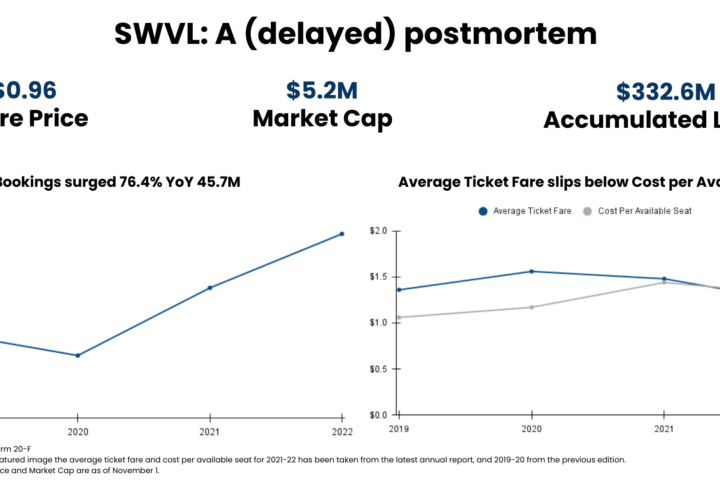

Swvl

SWVL entered the country in 2019 and announced plans to invest $25 Million in the market. At the time, they were offering heavy subsidies, and the rides cost as low as 20 cents. In 2021, Pakistan generated $9.72M in revenues for them and was only second to Egypt.

However, by its own account in the Harvard Business Report (HBR) case study, Swvl found the market to be unusually challenging compared to Kenya or Egypt. And last month, it announced a complete exit from the market, only months after first shutting its intracity service. This could be due to ad hoc changes in regulations, cultural norms, security concerns, or challenges with infrastructure.

This, however, is more a reflection of SWVL’s own challenges as a company than those of the Pakistani market. They are, at the time of writing this, trading at $0.19, and risk delisting from NASDAQ.

InDrive

InDrive entered the Pakistani market in early 2021 after raising $150 Million in Series C. Its unique model, which allows for haggling, has thrived in many developing countries and helped it achieve unicorn status. According to Apptopia, it was the world’s second most frequently downloaded ride-hailing app in 2021 with 41M installs.

In Pakistan, it has amassed over 5.5M installs since launch and sits on top of Google’s Maps and Navigation category. Two factors cemented its place as the platform of choice for drivers: cash-only rides and zero commissions. While the company does charge a 9.99% cut now, it’s much lower than competitors (whatever few are left). Since Uber announced its pullout, InDrive has expressed plans to expand in five more cities. According to industry insiders, the company already has a 70% market share with no serious competition looking to undercut it.

What’s ahead for mobility?

When you read this article in the context of the current funding climate, you can reach the unambiguous conclusion that it is expensive to scale in MaaS, at least in Pakistan, and VCs no longer have an appetite to fund this market. However, this would leave out the countless opportunities that continue to exist here thanks to the crumbling infrastructure. Buscaro’s angel round of $500K and ezBike’s $1M may be testament to how there’s still fuel in the sector.

However, VCs will likely want to see better unit economics in this space, and perhaps we will not be celebrating investments like Careem or Airlift for the foreseeable future. But this allows emerging players to exploit the “second-mover advantage”, as InDrive did, and learn from the previous models, use that talent, and creare a better alternative.

What a well written piece! Love the car puns and the way the information has been shared! Thank you for your hard work.