In May 2018, I ventured into tech journalism with my first byline, for Dawn. Right around that time, the Ministry of Information Technology and Telecommunication uploaded a draft Personal Data Protection Bill. Since then, a lot has changed; our economy has undergone three cycles and the exchange rate worsened from ~PKR 116 to PKR 284; we lived through a pandemic; and the startup scene ballooned from fringes to becoming a hot market before falling out of favor. Yet, that bill is still in the draft stages with the last version coming out in 2021. Why am I blabbering about it? Well, because the government recently released a new plan: the National AI Policy. And the pessimist in me says that this too will be another act of needless deforrestation.

Our policymakers have two modes — hypo and hyper activity. For things that matter, they go missing. But when it comes to cool stuff — like AI and CBDCs — boomers don’t waste a second before butting in. My theory is: regulators read articles in foreign publications or journals, get impressed, feel the need for similar frameworks in Pakistan, and introduce them here. Instead of letting the innovators do their job first and then figuring out the modalities, the policymakers beat them to it and create a formal structure first. We saw it happen with Electronic Money Institutions and then Special Purpose Acquisition Companies. Never mind the actual uptake, it’s more like a PR exercise.

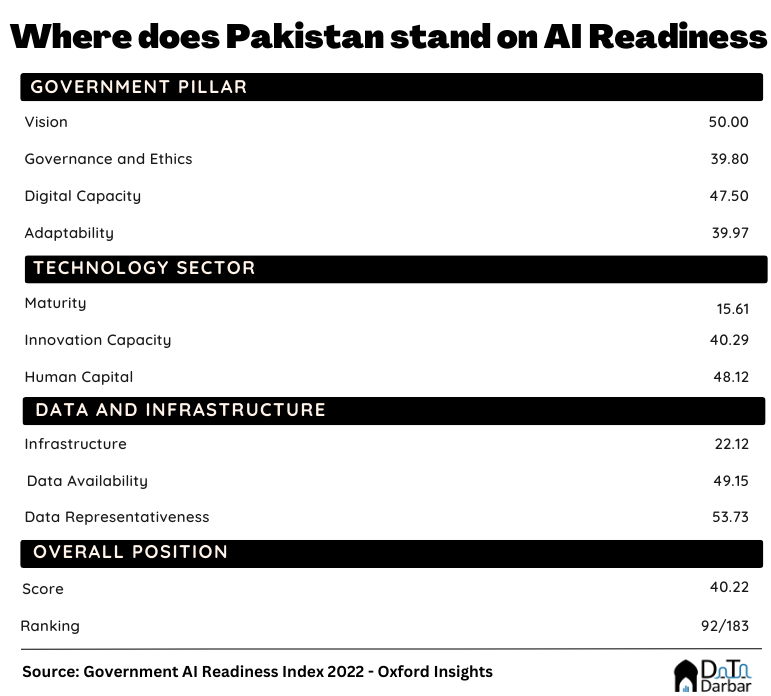

Okay but what’s the harm in having an AI policy? Other countries are doing it too, from the United States to Bangladesh. None, in fact we do need it. Only that it needs to be a well-thought out policy that reads more than a tediously long op-ed. It should be the landmark document on the subject. A first point of reference for anyone wanting to understand where Pakistan currently stands — across public and private sectors — and how we can move forward.

The (lack of a) Big Plan

Unfortunately, the draft is a subpar piece of work that barely scratches the surface of the topic. For instance, the entire section about the State of AI in Pakistan is summarized in two paragraphs with the usual boilerplate stuff. The kind you get from the top five search results on Google. Nothing on the market size, talent pool, or the magnitude of academic knowledge produced.

Sample this from the section about transforming health services using AI: “Many Pakistanis have chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and high blood cholesterol.” Only if there were actual numbers available on how many Pakistanis actually had those diseases. I mean there is existing literature on the prevalence of diabetes in the country or cardiovascular deaths, for instance.

Contrast this to India’s strategy from 2018 which talks about the demand and supply imbalance between healthcare services — 66% of the country is rural as compared to just 33% of the doctors. This makes it a key intervention area for the use of AI.

The four pillars of AI Policy

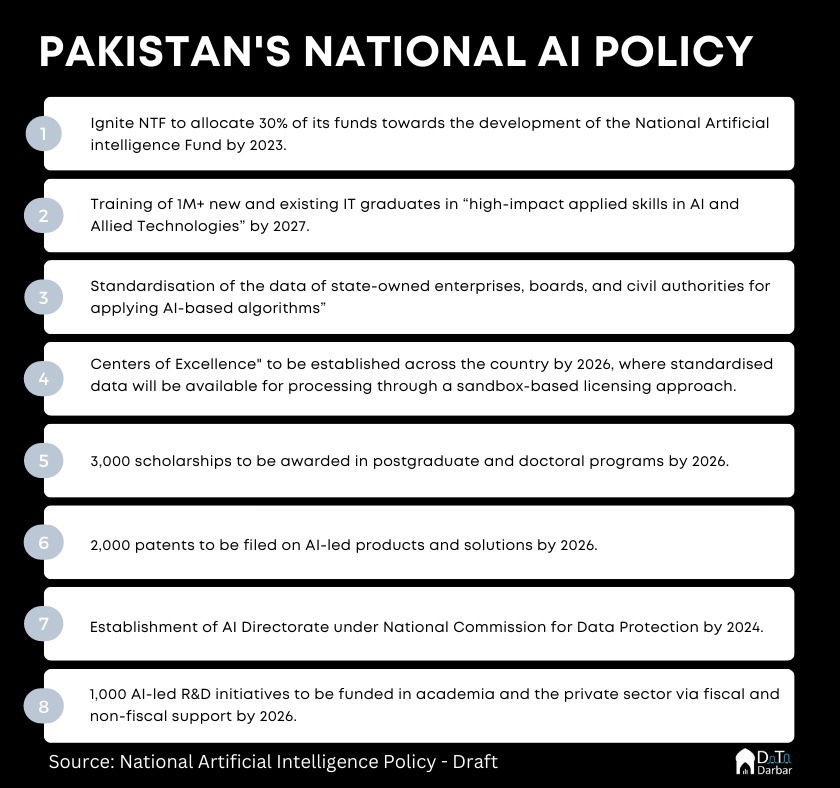

The draft is based on four pillars: 1) Enabling AI through awareness & readiness, 2) AI market enablement, 3) Building a progressive and trusted environment and 4) Transformation and evolution — further categorised into 15 targets.

The first pillar (it messes up the order) starts with proposing the establishment of a National Artificial Intelligence Fund, for which the Research and Development Fund (Ignite) will allocate at least 30% of its money on a perpetual basis. Of course, to administer it, you’d need up to 11 board of directors and a chief executive officer. Good times are here to stay (for boomer uncles).

Staying true to form, it proposes the most pressing requirement for the uptake of AI in Pakistan: Centers of Excellence. I mean the construction industry needs to make a living too. It’s already been tough for them without the amnesty scheme and the cuts in the Public Sector Development Programme. Sure, they are to be more than just buildings, you know like those incubators turned out.

The last part of this pillar is actually valuable for it proposes “standardising the data of state-owned enterprises, boards and civil authorities for applying AI-based algorithms”. It will allow tech companies to train their models through a sandbox-based licensing approach, under the Centers of Excellence. Think of large datasets in health, education, utilities opened to tech companies to train their models on. If executed correctly, the impact could be massive especially in medical diagnostics, where a couple of local startups already operate.

The document delves into potential use cases for each sector, from transforming health services to intelligent learning and assessment. However, this whole section reads a lot like someone asked ChatGPT for AI applications. Sample this part: “The biggest challenge in the agricultural sector regarding supply chain optimization is data digitization and standardization.” I am no agri expert but wasn’t our biggest challenge the lack of infrastructure? You know like cold storages and efficient transportation? There’s nothing wrong with the identified areas for intervention, except for the lack of substance.

Creating targets out of thin air

Moreover, the policy lays out lofty targets for training the workforce — with a target of upskilling one million existing and new IT graduates in “high-impact applied skill in AI and Allied Technologies” by 2027. This will require 10,000 new trainers. The ministry, through the centers, also plans to organise an internship program which will offer at least 20,000 placements annually in collaboration with the private sector.

How do they get to this number? We have no idea. After all, it’s almost the size of Pakistan’s entire information technology sector workforce. Which by the way includes non-technical roles in sales, market etc. Currently, the country produces 25-30K tech graduates annually so with this pipeline, the 1M goal might have to wait longer. This practice of setting random targets, devoid of any fundamentals or justifications, is a pastime favourite of our policymaking circles. Be it for account opening, textile exports or anything else. And never do we remotely come to achieving them. Even Goodhart’s law fails here.

It also envisions a scholarship program which will fund 3,000 deserving candidates on open merit every year in postgraduate and doctoral programmes across the country. Additionally, there’d be 500 seats for women and 100 for persons with disabilities.

The policy seeks to encourage the production of academic knowledge on AI from Pakistan and through CoE proposes a logistical/fiscal/data support for up to Rs200,000 per thesis or paper, leading to publications of regional or international journals. “At least 200 such journals/whitepapers and other research materials shall be supported and published.” It also aims to help file 2,000 patents on AI-led products and solutions from the country. Again, what determined the level of these targets is not clear.

An AI Directorate will also be set up with the goal “to augment the development of AI-based initiatives through need-based assessment of regulating different functions automated using AI and the type of data being created and processed for defined purposes.” Basically, it will provide regulatory support for most issues related to artificial intelligence, from standardization of data to formulating policies for developing computing and connectivity infrastructure.

For the sake of brevity, we have left out some details, specifically those relating to the modalities and processes. Which is what the AI policy really seems to be about: checking off boxes. Or at best, a wish list. AI is all the hype these days and countries around the world have produced their strategies in dealing with it, so how can we stay behind? Even if the paper it was printed on will be used to serve samosas. Or one can hope the final version is not written like I did my undergrad assignments: night before the deadline.

A shorter version of this article first appeared in Dawn.