Pakistan’s National Assembly is extremely busy these days, churning out new legislation like LinkedIn influencers do their posts. In the first four days of August, they passed 11 bills — the highest since the full month of June 2022. Even if no one really reads the details because let’s be real, that is for lame nerds. Not for the chads occupying the lower house. However, this may not be the case with the upcoming Personal Data Protection Bill, considering that it’s the fourth draft since 2018.

While the latest iteration is yet to table, the legislation has created unease among certain stakeholders. The Asian Internet Coalition, a Singapore-headquartered lobby group representing the biggest tech companies in the world, issued a 5-pager feedback on the updated draft. Earlier in April, it had released a more detailed document with recommendations.

So what’s in the Personal Data Protection Bill 2023 that’s causing this unease? Let’s start with a primer. As with most legislation or policies in the country, at least related to financial markets and technology, the latest draft contains a pretty standard set of items that are common across most such regulations and jurisdictions.

That’s because they all usually follow Europe’s GDPR — which is basically THE benchmark. The template is similar: start with establishing the owner and processors of data, the terms dictating their relationship, how it should be stored and the conditions for flows. Let’s go over the key pointers.

[Disclaimer: the pointers will be in English so naturally will corrupt the legal-speak of the document. We have only focused on what felt like the most important details and ignored some aspects.]

1. Applicability

It starts with the grounds for processing personal data, which shall be collected for “specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes”. Additionally, the controller and/or processor needs to be registered with a proposed National Commission for Personal Data Protection as long as it is digitally or non-digitally operational within Pakistan.

That means entities without any legal presence locally will also be bound by this law and need to treat data of Pakistani users accordingly. This includes profiling for both commercial and non-commercial activities. Understandably, the AIC wasn’t too amused and had recommended in April: “Any data fiduciaries or data processors not established within the territory of Pakistan who carries out the processing of personal data of data principals located in Pakistan, where such processing is related to the offering of goods or services to data principals in Pakistan; or profiling data principals within the territory of Pakistan.”

2. The fifty shades of personal data

It defines personal data as “any information that relates directly or indirectly to a data subject, who is identified or identifiable from that information or other information in the possession of a data controller and/or data processor, including any sensitive or critical personal data. Provided that anonymized, or pseudonymized data which is incapable of identifying an individual is not personal data”. But that’s only the tip of the iceberg as not all data is equal. Therefore, the draft specifies two additional layers: sensitive and critical personal data.

- “critical personal data” means such personal data retained by the public service provider – excluding data open to the public – as well as data identified by sector regulators and classified by the Commission as critical or any data related to international obligations;

- “Sensitive personal data” means any personal data relating to:

- financial information excluding identification number, credit card data, debit card data, account number, or other payment instruments data;

- health data (physical, behavioural, psychological, and mental health conditions, or medical records);

- computerized national identity card or passport;

- biometric data;

- genetic data;

- religious beliefs;

- criminal records;

- political affiliations;

- caste or tribe;

- individual’s ethnicity

The initial version of the draft included passwords and financial information without any exclusions. However, after incorporating the AIC’s feedback, these changes were made. Though from a Pakistani perspective, it might have made sense to treat those two as sensitive data considering how frequent their breaches are, be it public sector organizations like the FBR or private companies like NIFT. So having some safeguards to protect such data seems like the right step.

3. Do you consent?

The prerequisite for that data collection is understandably consent of the subject, which must be “a free, specific, informed, and unambiguous indication” of their intent signifying to the agreement. More importantly, the user will have the right to withdraw that consent at any time, post which the processing of personal data needs to end, barring a few exceptions such as compliance with a court order etc.

While this is relatively one of the more agreeable parts, the AIC had sought one change here. It asked for the data fiduciary to be able to process data, even without the subject’s consent, as long as it’s for legitimate interests. In the latest draft, this bit was incorporated. But what exactly counts as legitimate interest sounds extremely subjective.

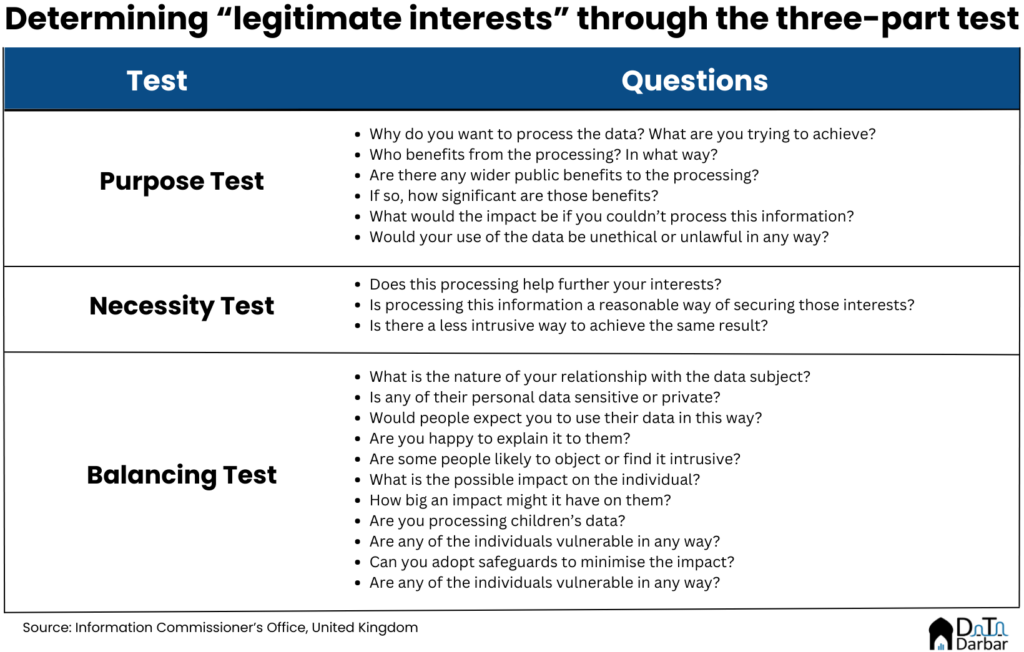

Luckily there’s some guidance available. For example, the Information Commissioner’s Office in the United Kingdom proposes a three-part test to assess the legitimacy of interests, based on 1) necessity 2) purpose and 3) balancing. Similarly, GDPR — the inspiration behind AIC’s recommendation — requires the processor to explicitly and specifically inform the subject what that legitimate interest is. Some of the examples of what would constitute legitimate interest include:

- Fraud prevention

- Network and information security

- Indicating possible criminal acts or threats to public security

4. Keeping it PG-18

There’s a special section on processing the personal data of children — defined as anyone under 18 — with the controller required to verify the age and seek parental consent. What’s significant is that it requires the processor to “not undertake tracking or behavioral monitoring of children or targeted advertising.”

However, the AIC feels that the definition of children should be <13, in line with other regulations around the world, and the current definition is tantamount to locking children out of the digital economy, and perhaps even to educational content. Though there is some weight behind AIC’s argument, the definition of children is not only in line with the broader legal age in Pakistan but also with how other countries, such as India, treat it in their own data bills.

5. Virtual Protectionism

For cross-border transfer of personal data, the bill requires that the host country has at least a similar level of protection as here, provided there is the consent of the user and it does not conflict with the public interest or national security. Meanwhile, critical personal data can only be processed in a digital infrastructure located in Pakistan.

This is the single-most controversial part of the bill, drawing serious criticism from all quarters. The Venture Capital Association of Pakistan spoke out against the bill, stating that it “may hinder the growth of the nation’s digital economy and discourage foreign investment”, since it essentially outlaws hosting any critical personal data on global cloud services providers (CSPs) like Amazon Web Services or Azure. Meanwhile, the Digital Rights Monitor raised apprehensions regarding the state’s intentions to control and access data through this bill.

There’s absolutely no doubt that any restriction on the use of global cloud will be immensely damaging for tech-enabled companies. Honestly, it’s almost unimaginable for either startups or established businesses (trying to make their infrastructure scalable) to not opt for global cloud providers. That level of flexibility and agility is just not possible in Pakistan. Yes, local CSPs exist but they are both more expensive and slower than their international counterparts.

The civil rights organizations also have a solid point: our state institutions have shown a penchant for excesses and love infringing on people’s privacy, along with other rights. Giving them a blank slate to define national interests as they see fit will come to bite us sooner or later.

However, let’s also not forget that residency laws and restrictions on cross border transfers aren’t exactly unique to Pakistan. According to McKinsey, 75% of all countries have implemented data localization on some level. And the regulators across the globe generally think along similar lines, often in direct conflict with what the industry wants.

In theory, data localization requirements are not as exceptional as one may make them out to be. But in the absence of efficient local cloud services, the law would do more harm than good. Now you can argue that other countries tackled this by developing and incentivising their cloud infrastructures.

Sounds fair, but let’s remember that building such an infrastructure requires money. Ideally with a significant foreign component from investors who have the right expertise. How are we going to attract the capital though? Considering that the total foreign investment for hardware development over the last six years is a cumulative $7.9M, as per State Bank. That might not even be enough to start a chilghoze ka thela.

Most importantly, cloud computing has become quite sophisticated technologically with AI and ML (apologies for the buzzwords). And if we limit ourselves to relatively primitive local providers, it’d block out our talent from the latest developments in the world of tech. So while that protectionism may work, everyone could end up worse off, except for the domestic CSPs of course.

Ignorance Incompetence is bliss?

All said and (not) done, let’s hold our horses. Because will this data bill draft, like its predecessors, even see the light of the day? I mean, it’s the fourth try and we are in the same place as in 2018, legislation-wise. Despite a very clear need for data laws.

But even if it became law, in whatever final form, the bigger question is obviously enforceability. We all know that the existence of legislation, in no way, guarantees its implementation. Even in sectors far less complicated to regulate than data. In this regard, the government’s big plan is to levy hefty fines.

For instance, anyone who processes/disseminates/discloses personal data in violation of the act will be fined up to $125K and $250K for repeat offenders. In case of sensitive and critical personal data, the amounts go up to $500K and $1M, respectively. Similarly, a failure to adopt appropriate security measures will result in a penalty of maximum $50K. The list goes on, though it remains unclear if they would apply on the biggest offenders i.e. public sector organizations.

However, fines can only be one part of the enforceability leg. The more important layer will always be the proposed Data Commission, which will need to formulate a monitoring framework. And that, at the end of the day, will comprise sarkari boomers.