Every few months, development and public sector professionals gather in upscale hotel halls to ponder about the dismal state of women’s financial inclusion in Pakistan. Among the esteemed audience are also financial services boomers, the same people whose institutions routinely humiliate women customers, from widowed pensioners to single mothers.

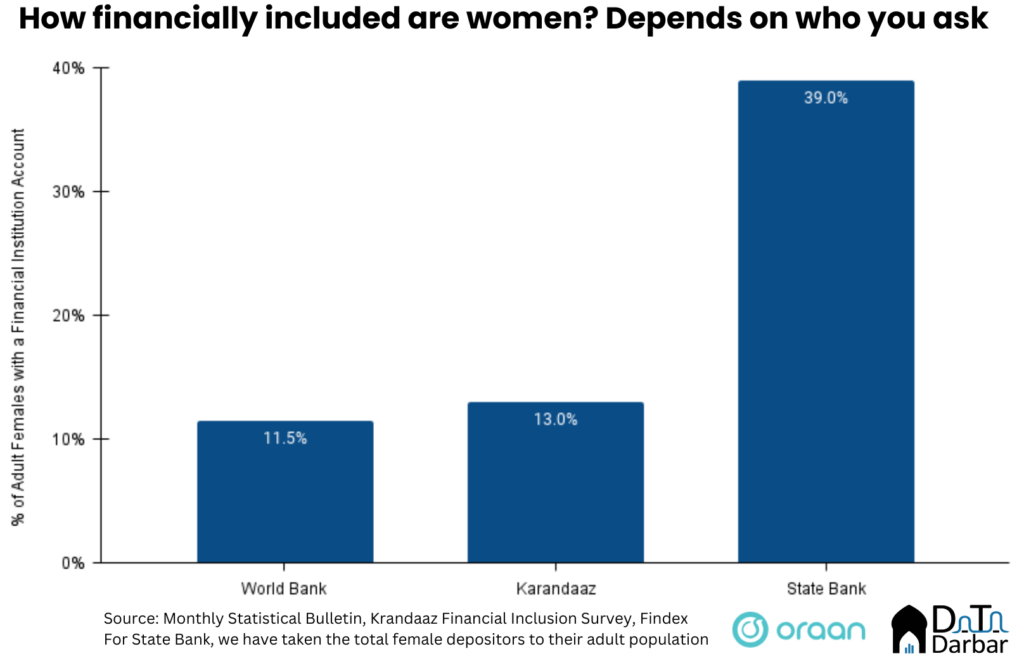

According to Karandaaz’s latest Financial Inclusion Survey, 13% of the Pakistani women have a financial institution account. While that’s an improvement from the previous edition back in 2017, the level is still below the lofty targets. Which is pretty funny because during this time, there have been countless events where bankers — the same people responsible for this mess — give their solutions, while the rest of the sycophants clap their way. Or maybe it’d have been funny if it weren’t so sad. Because despite years of policies, whitepapers and conferences, Pakistan has barely moved the needle on female financial inclusion.

Where do we stand on female financial inclusion?

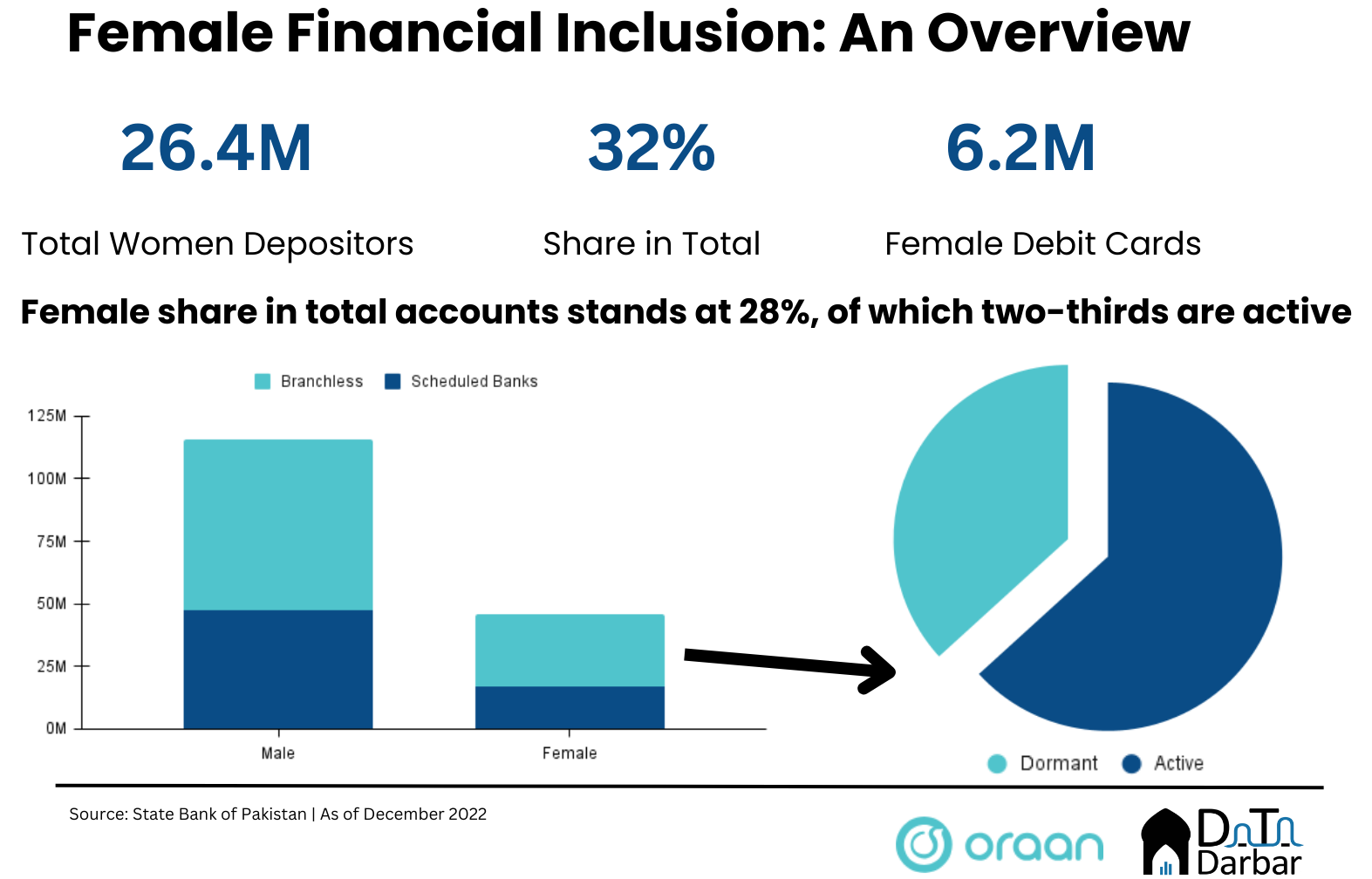

So how bad is the situation really? If you are to take the State Bank’s words (and the few numbers they share), there has been significant progress. For starters, the number of female bank accounts increased from 13.1M in June 2017 to reach 45.95M by December 2022. That means more than twice as many accounts have been opened in the last five and a half years than our entire existence before.

Consequently, female accounts as a percentage of the respective adult population jumped to 67.5% by December last year, up from 22% in June 2017. Amazing growth, right? A little too good to be true, if you ask us. Because this figure is six times what the World Bank estimates in the 2021 edition of Findex (11.5%). This big difference is questionable: either about the survey methodology or the value of the reported numbers.

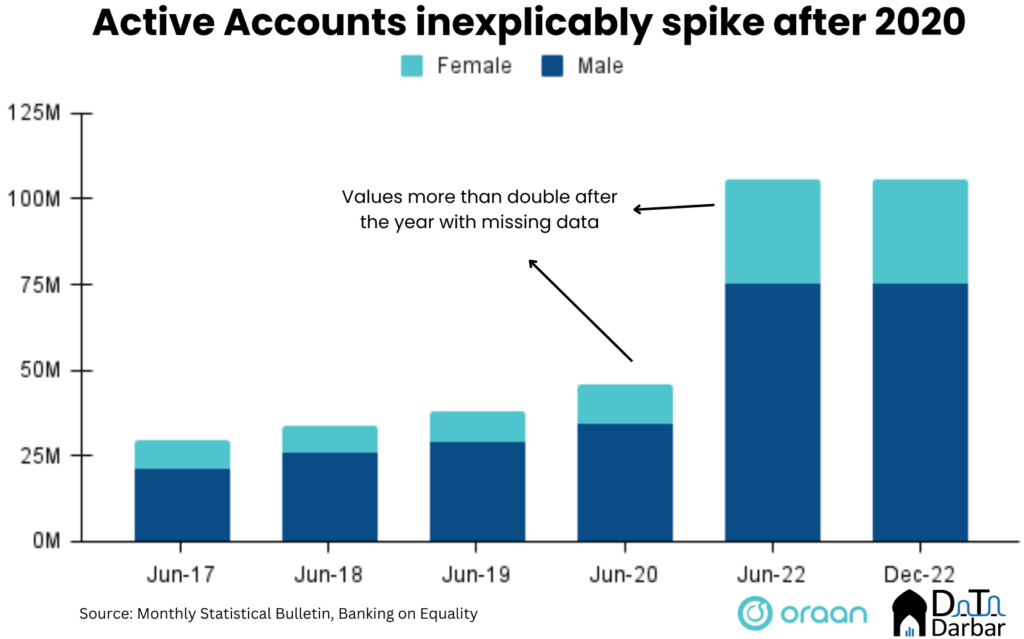

But before we get into that, let’s peel a few more layers of this onion. The number of active female accounts also increased to 30.5M as of December 2022, showing visible progress compared to only 8.4M back in 2017. Put another way, over two-thirds of all women-owned accounts are active — even edging out the corresponding ratio for males at 64.9%.

Similarly, active women-owned accounts as a percentage of adult female population improved to 44.9% by 2022, twice as much compared to June 2017. Somehow, this ratio is also higher than the corresponding figures for males. That said, the number of accounts — whether total or active — is probably not the best metric as many people have multiple. This is where unique depositors come in for which the SBP recently published data.

Read: How women spend (digitally) in Pakistan

Devil is in the details

According to the regulator, there were 28M unique female depositors in Pakistan as of 2022, of which 21M were active. That means women make almost 35% of all depositors in the country. Another way to put it: 39% of all adult females have at least one bank account.

Deceiving as the numbers may be, there are a few measures to assess the quality of accounts women can access. First of all, 28.7M — or 62.5% of the total — female accounts were branchless as of 2022. This is not just for women: the corresponding share for males was also 59%. While it’s great that players like JazzCash and Easypaisa are filling the gap where legacy financial institutions fail, mobile money wallets nevertheless offer an even tamed down version of banking.

Secondly, the number of female-owned debit cards stood at just 6.2M as of December 2022. That’s 19% of all debit cards in the country. Put another way, only 36.2% of the scheduled banking accounts of women had a debit card, compared to 55.3% for males. So even when women do have a proper bank account — not a digital wallet — they are far less likely to get something as basic as a debit card.

The fault in our data?

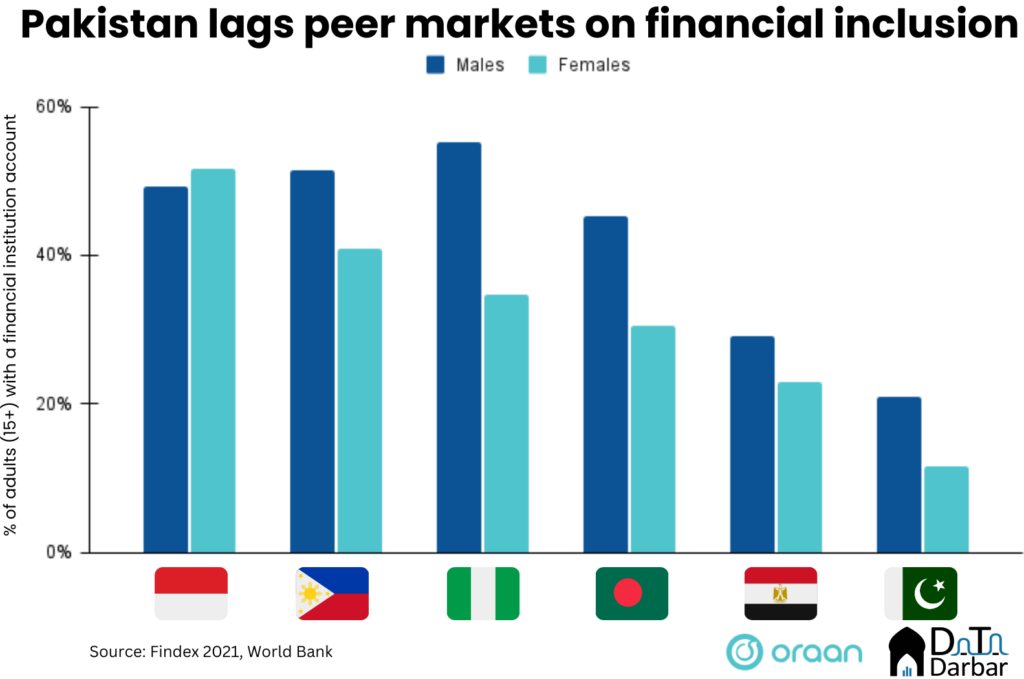

As we mentioned, if we go with the above data, it means the level of women’s financial inclusion in Pakistan is substantially higher than previously believed. In fact, our performance is apparently even better than peer markets like Indonesia and Bangladesh. Sounds too good to be true.

There are also issues with the reporting of data, starting with the fact that 2021 numbers are missing. That also happens to be the year when apparently most of the progress was made. For example, active accounts of both males and females more than doubled between 2020 and 2022. What’s the explanation for them jumping so substantially, far outpacing the historical growth trends? Our guess is as good as yours.

Then, some values don’t really add up. For example, the sum of female and male accounts in June 2019 was 62M, whereas total accounts stood at 92.9M. Where exactly are the remaining 30.9M coming from? We don’t really know because the value is too big to be explained corporate and NBFI accounts. It would have been very simple if the State Bank had followed through on the Banking on Equality policy and disclosed gender-disaggregated data. But that’d have killed all the fun, right?