On September 22, Singapore-headquartered Foodpanda announced they were conducting a fresh round of layoffs, the third in the last two years. This development comes as its parent, Delivery Hero, also confirmed that it is looking to sell operations in select Southeast Asian countries at a reported value of $1.07B. Based on a 2023E forward estimate, it translates into a GMV multiple of 0.181. According to Foodpanda CEO Jakob Sebastian Angele, this is a drive to make a leaner, more efficient, and agile organization.

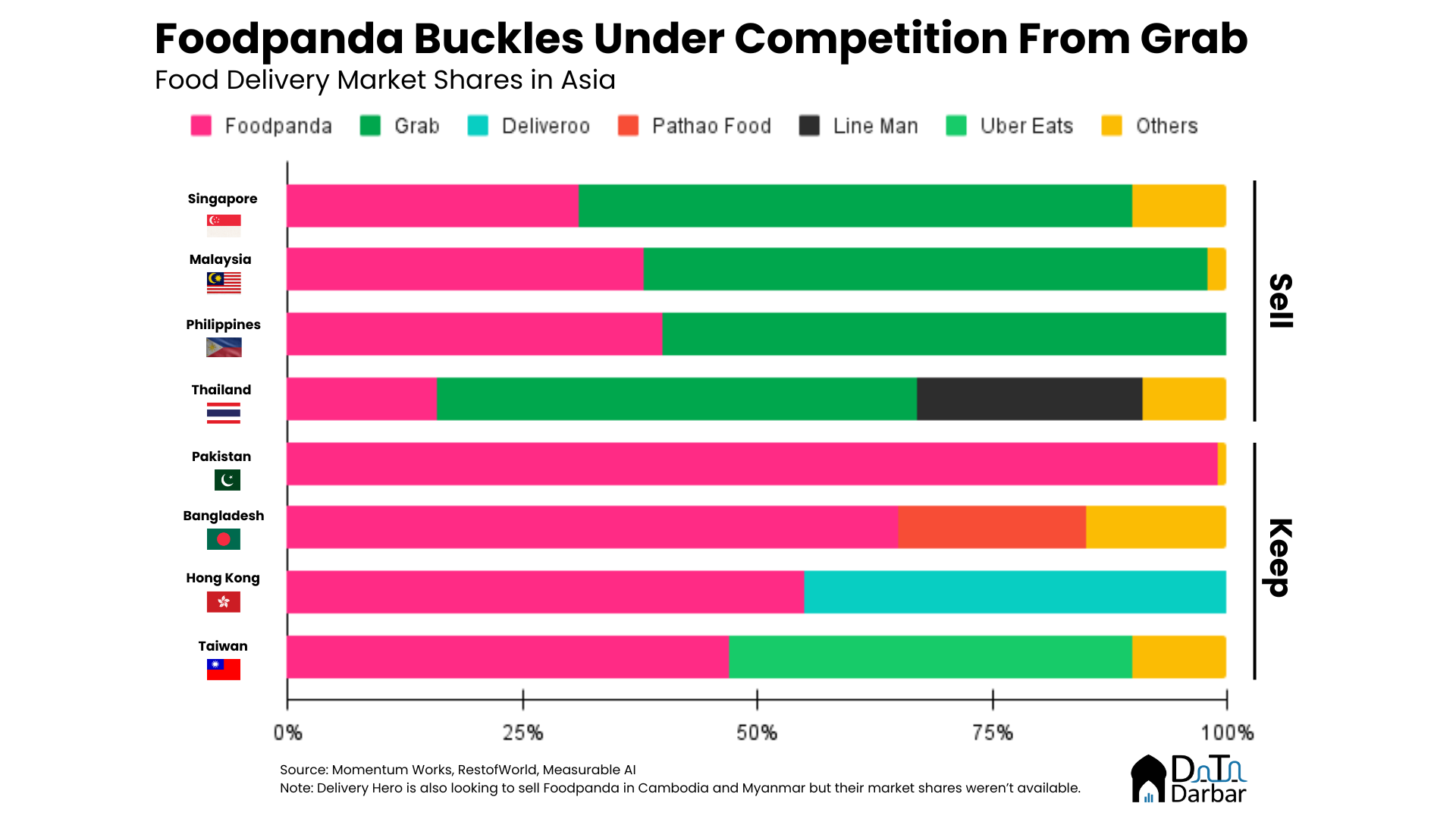

As per reports from German media outlet WirtschaftsWoche, Delivery Hero is looking to sell food delivery operations under Foodpanda in the following markets: Singapore, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines and Thailand. These are also the countries where Foodpanda faces fierce competition, which curtails its profitability, as it spends on marketing and keeps its pricing competitive. Rumours suggest that Grab is the probable buyer as it looks to consolidate its market share through this acquisition.

A primer on Delivery Hero brands and geographies

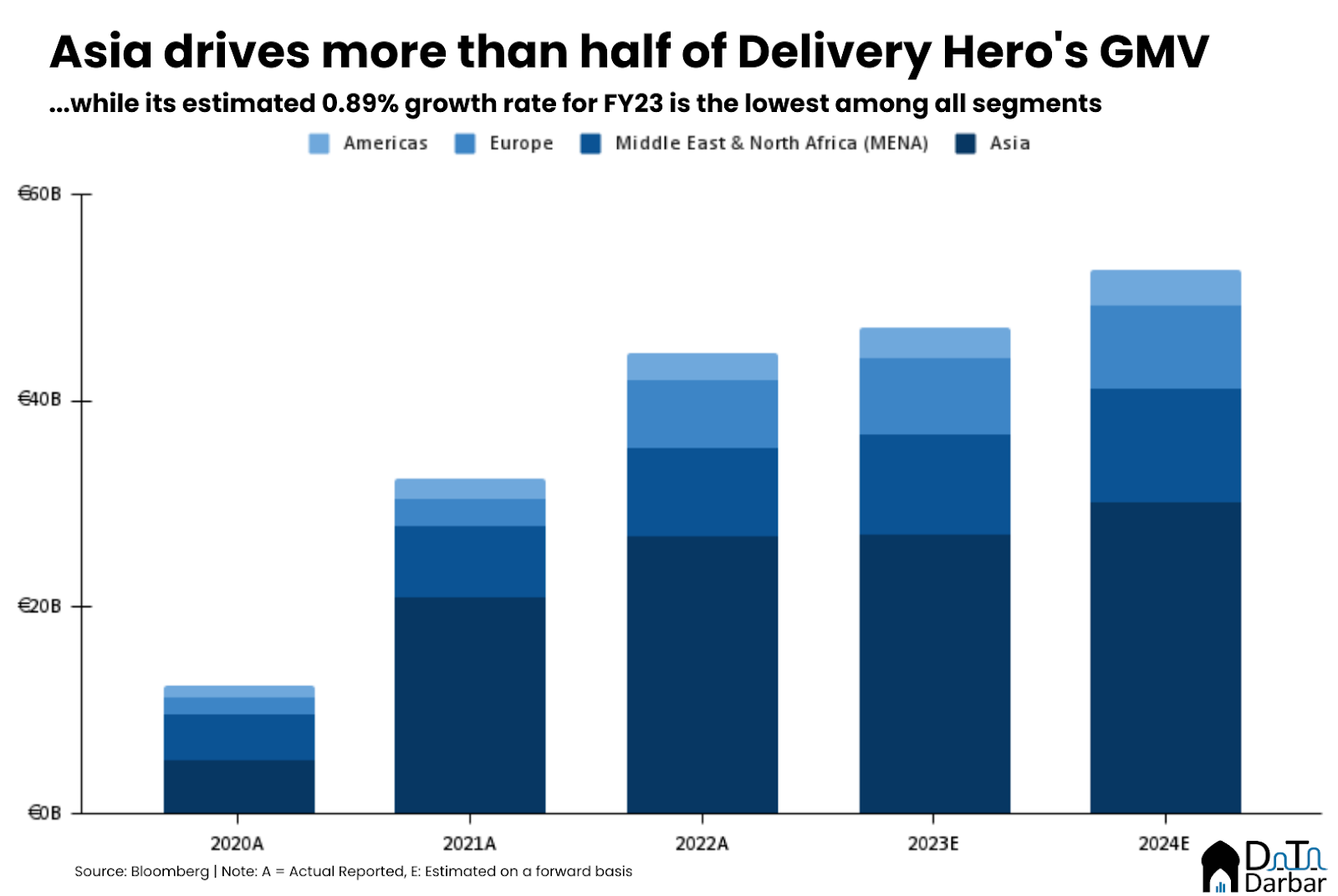

Before we get into more details, let’s first understand Delivery Hero as a business. That means finding out what markets earn it the most money and what its key revenue sources are. Since Asia contributes more than half of the group’s gross merchandise value (GMV) and is also where DH is selling parts of its business, it is appropriate that we put our focus there.

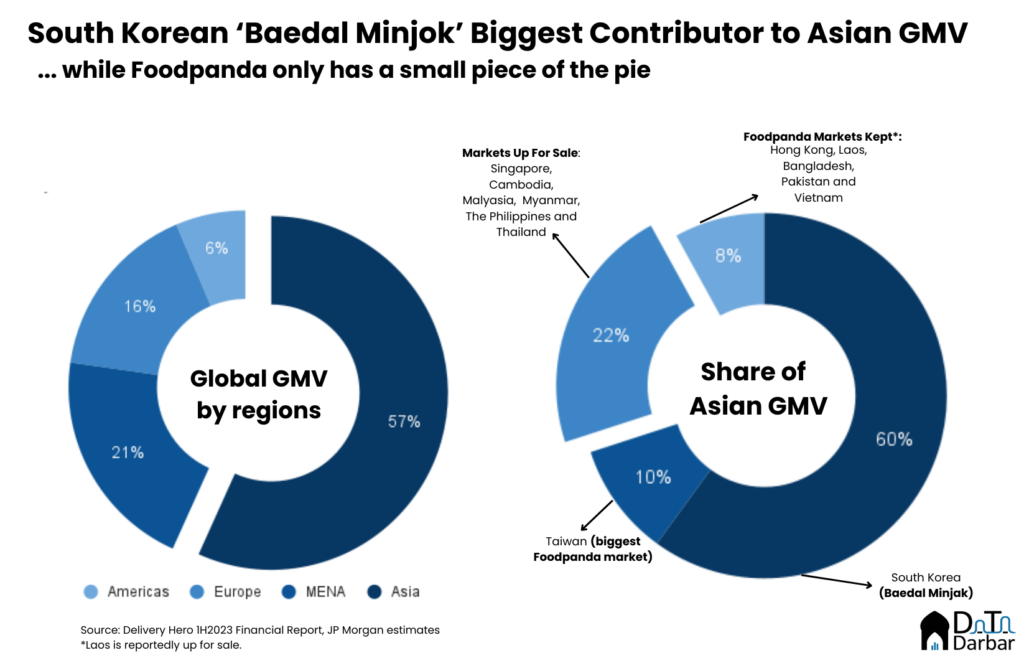

In 1H2023, Asia had a GMV of €12.64B, or 56.7%, out of the group’s total €22.28B. However, this dominance is not because of Foodpanda. Instead, the credit goes to South Korea’s Baedal Minjok, which DH acquired in South Korea and accounts for 60%2 of the region’s GMV. A note from Barclays’s Andrew Ross and Emily Johnson describes it as “amongst the best food delivery business on Earth.” More importantly, the market is expected to post a free cash flow of €500M3 in 2023.

One problem with the Asia business is that growth has slowed down across most metrics. GMV is expected to only increase at 0.89%4 and revenues at 5.12%5, the lowest among all geographies. Though exact numbers (or estimates) aren’t available at country or brand levels, Taiwan is reportedly the largest geography for Foodpanda, contributing 10%6 to the group GMV. In comparison, five countries add another 8%7. These are the regions where Delivery Hero either has a monopoly (Pakistan) or is the bigger of the duopoly (Hong Kong).

Meanwhile, the seven markets up for grabs account for 22%8 of the GMV. But the problem is that these geographies face stiff competition, with Foodpanda’s market share lagging. That puts pressure on pricing and the path to profitability, thus explaining why Delivery Hero may be looking to sell them.

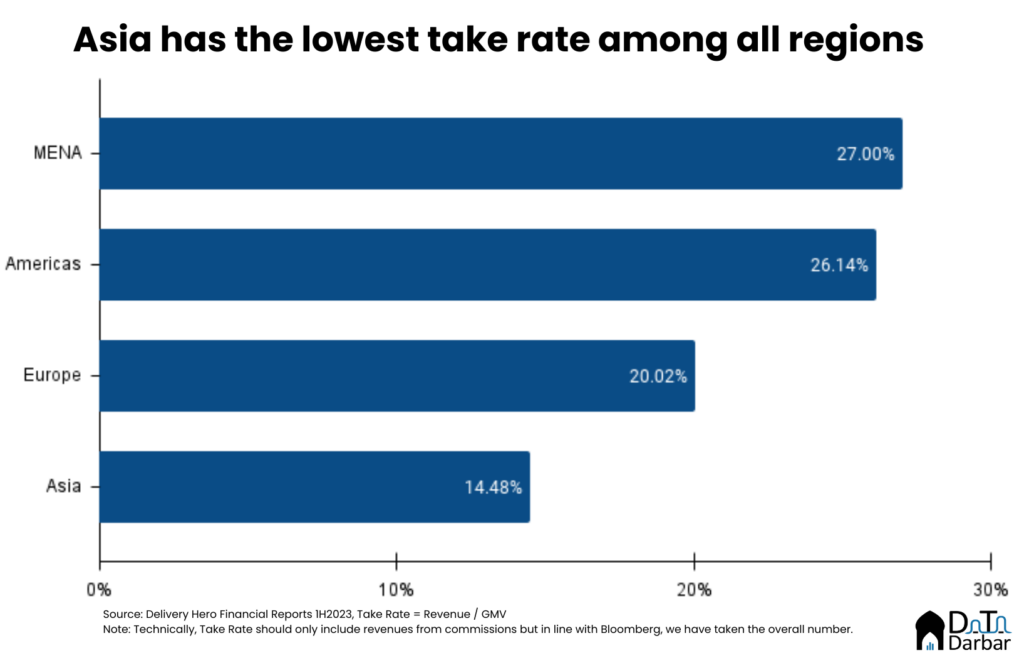

Of all the regions, Asia also has the lowest take rate — the percentage the company keeps, i.e. revenue-to-GMV — at 14.6%. In terms of EBITDA, the region does relatively well with margins of 1.4% in 1H2023, second only to MENA’s 2.5%. On the other hand, Europe and the Americas were in the red. However, South Korea alone contributes most of the EBITDA. According to Barclays, Baendal Minjok’s EBITDA will be €700M in 2023. Meanwhile, the median value for Asia as a whole is €392M, as per Bloomberg. Basically, the rest of the region is still negative.

Essentially, DH wants to optimise its portfolio and focus on geographies with either existing or a path to future profitability. The move has long been on the cards, and analysts had explored M&A long before the recent news came out. One note from JP Morgan recently also talked about a potential disposal of the Americas operations, for it will have a much larger impact on the group balance sheet than divesting from small markets.

Delivery Hero Goes Looking for New Revenue Streams

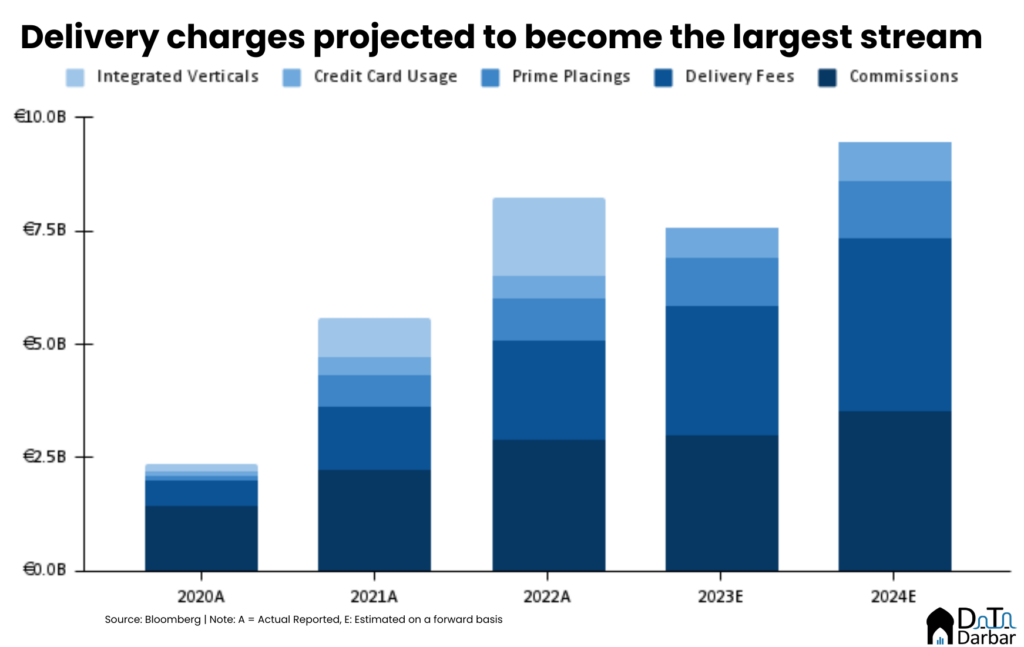

While it looks to exit parts of Southeast Asia for profitability, DH is also trying to diversify its revenue mix. The company makes most of its money from commissions, which accounted for 38.51% of the topline in 1H2023. However, delivery charges are fast closing the gap and are projected9 to overtake as the largest stream in 2024. Foodpanda regulars in Pakistan know this all too well from their experience.

The reliance on these two streams has long frustrated DH’s primary stakeholders, i.e. restaurants, delivery riders, and consumers. The tiered commission structure, which charges smaller restaurants higher fees than the larger ones, has caused smaller restaurants to complain about inequity. In Pakistan, there was even a boycott of the company back in 2020. The labour issues are also well-documented, with countless instances of riders protesting across various countries. For the customers, it means heavy discounts are going to get scarce. Though the group is still projected to spend €833M10 in vouchers, the rate of increase has visibly slowed down.

To further optimize logistics, the company has also started doing deliveries in batches. Maybe that’s why your orders are getting delayed and food’s arriving cold? The gains for DH are obvious, as it saves on energy costs. For each batch delivery, the orders must be from the same restaurant, and the dropoff addresses must be in proximity for the rider to fulfil them in an hour. Doing so obviously requires a certain scale, which the company has reached.

There’s more to DH’s crusade towards profitability. It has also introduced in-app ads, allowing brands to promote their products on the checkout screen as customers wait for their orders. This differs from advertising on the restaurant side, where restaurants pay to boost the position of their listings. This stream has existed for a while. In fact, prime placements contributed 10.07%11 to the company’s total revenue in 1H2023.

What it means for Foodpanda Pakistan

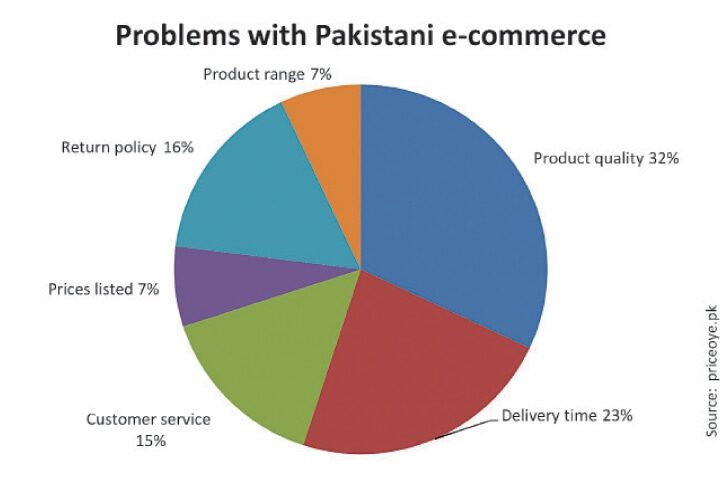

Okay, all of this is fine, but what does it mean for us in Pakistan? Would the sale change anything substantially here? Umm, no and yes. No, because here, Foodpanda enjoys a dominant market share, with volumes reportedly only second to Taiwan. However, value is a whole different story, thanks to both (relatively) lower average order values but also the depreciation of the rupee. Like any business, these guys have also seen their numbers get diluted every second day due to the rupee’s decline.

However, with no competition in sight, Foodpanda is now looking to extract more value from its volumes. Basically, they will exercise the pricing power for which they spent years subsidizing growth and creating a monopoly. For customers, the changes are hard to miss: delivery charges have become steeper, there’s a platform fee, subscriptions are in place, plus now you gotta see those ads too. However, small restaurants and riders are unlikely to get a bigger share of this pie.