Do you hate carrying cash and would much rather pay for everything by card? But can’t do that because even the biggest brands often refuse to accept digital payments? That’s because Pakistan’s point of sale ecosystem is extremely small, with throughput accounting for just 1% of the nominal gross domestic product in FY22. That too after a recent bout of growth, which saw the industry make some progress. However, a recent regulatory change has worried both the incumbents and new entrants.

Point of sale: understanding background and unit economics

Point of sale (or digitally paid) transactions are fundamentally unique, because unlike cash, the amount paid doesn’t equal the amount received. A small portion of the sale goes towards the many parties facilitating the transaction, directly deducted out of the vendor’s share. It’s called the merchant discount rate and is divided between multiple stakeholders. Of this, a sizable component is the interchange reimbursement fee (IRF).

That includes the customer’s bank, the card scheme (Mastercard/Visa), the processor (usually Euronet) and the acquirer who runs the point of sale machine. Until early 2020, there was no minimum MDR mandated by the regulator and it was basically determined by negotiation. Bigger merchants could get their way to a lower rate with acquirer bearing the costs out of pocket. The IRF was around 1.2-1.3% for debit and 1.5-1.6% for credit cards. This made acquiring a loss-making business, leaving them no incentive to deploy more machines.

To amend the problem, the State Bank of Pakistan in Jan’20 mandated that MDR needs to be between 1.5% and 2.5%. It also reduced the IRF and capped it at 0.5% for debit and prepaid cards, while not doing anything for credit cards. This basically distributed the pie to the acquirer from the issuer.

What the latest issue is

In a circular on Mar 17, the State Bank of Pakistan changed this MDR regime. It capped the interchange fee at 0.2% for debit and prepaid cards, and 0.7% for credit cards. Moreover, it abolished the floor of 1.5% on MDR. The move didn’t sit too well with players in the ecosystem — both issuers and acquirers.

Why? The issue goes back a few months when fuel stations were not accepting card payments because their total margins were already fixed by the Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority. And digital transactions ate a part of that in an already tough market for the industry as prices were shooting up and rupee nosediving. To address the issue, the SBP met with the stakeholders who agreed to a lower MDR specifically for oil marketing companies. Apparently, the regulator took it as consent for an across the board cut in the rate.

This has ruffled up the players. Their argument is that the removal of floor will trigger price wars between acquirers as they will undercut each other, bringing down the MDR. Wait, isn’t that a good thing and shouldn’t it make POS machines more acceptable because the merchant will get a higher amount for each sale? Isn’t this what worked wonders in India, especially for startups like BharatPe?

Theoretically, yes. Lower (or even no) MDR should definitely make digital payments more acceptable to merchants. But there’s a cost to build and run that infrastructure, which someone has to bear. If not merchants, then who else? You certainly can’t charge already price sensitive customers and expect much uptake. So either investors, acquirers (through their cash flow from other businesses) or the government need to take the financial hit. The money has to come from somewhere: it can’t be created out of thin air.

Someone’s gotta pay for it

However, with venture funding slowing down and recalibrating, it’s difficult to imagine investors subsidizing such costs in the foreseeable future. As for acquirers, it’s important to make a distinction between banks and fintechs. Because for the former, point of sale only makes a tiny contribution to income and can theoretically fund it from other streams. But for the latter, acquisition is typically the entire business and MDR the main source of revenue. Take it away and there’s nothing left.

This leaves only the government, which usually means money from the taxpayer. Or unless the SBP is willing to bear the cost, like it is doing for Raast. That includes subsidizing the terminals, which are primarily imported and thus become more expensive with each round of devaluation. Otherwise, it’s just not possible to have very low MDR. Well, because the players building the very digital payments infrastructure need to have some incentives.

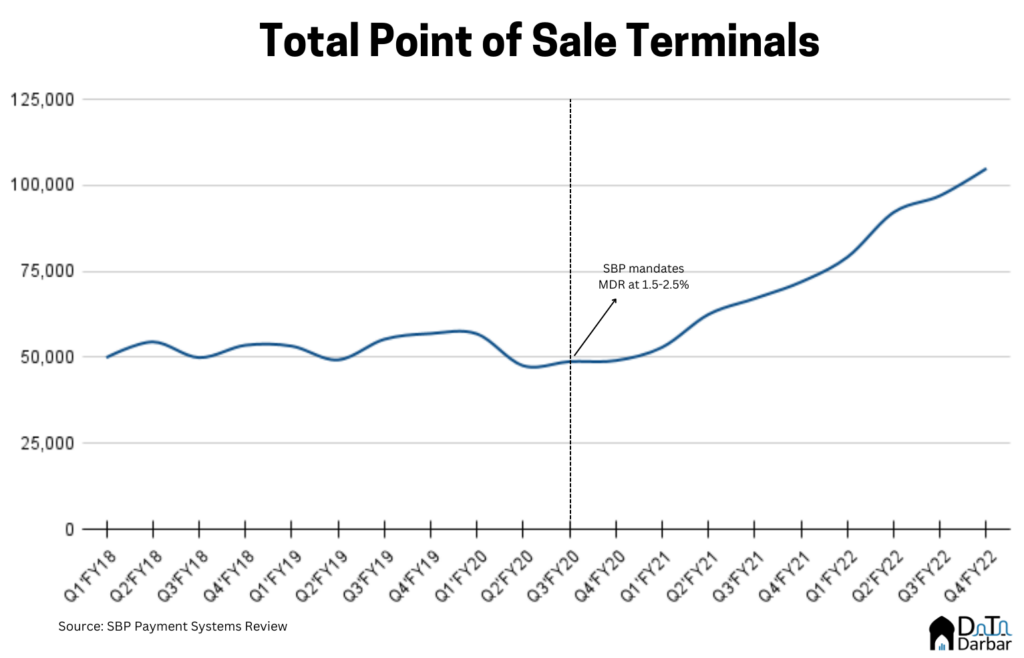

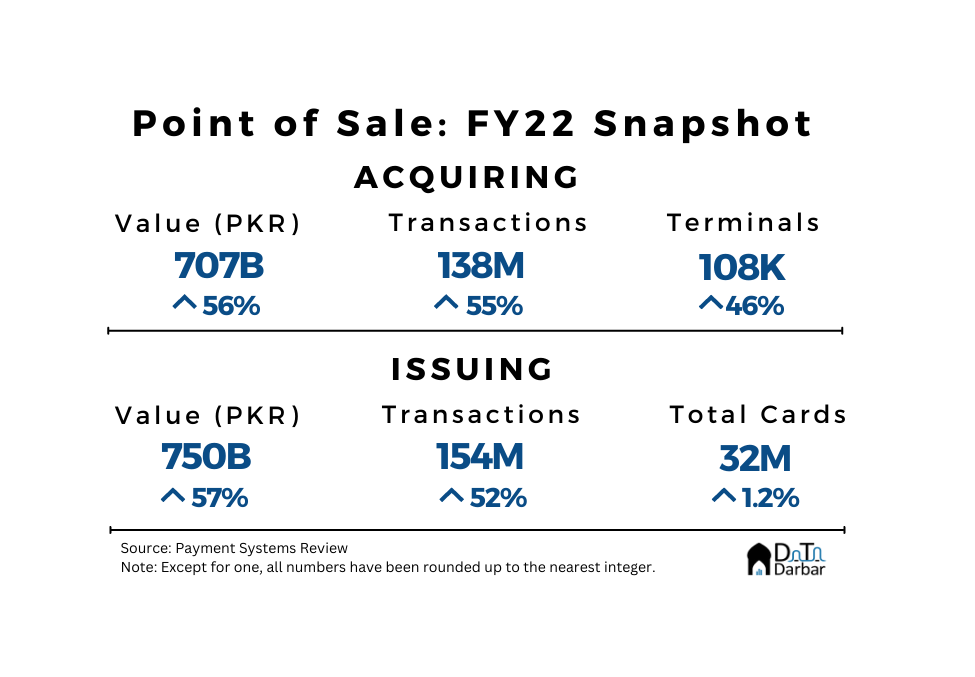

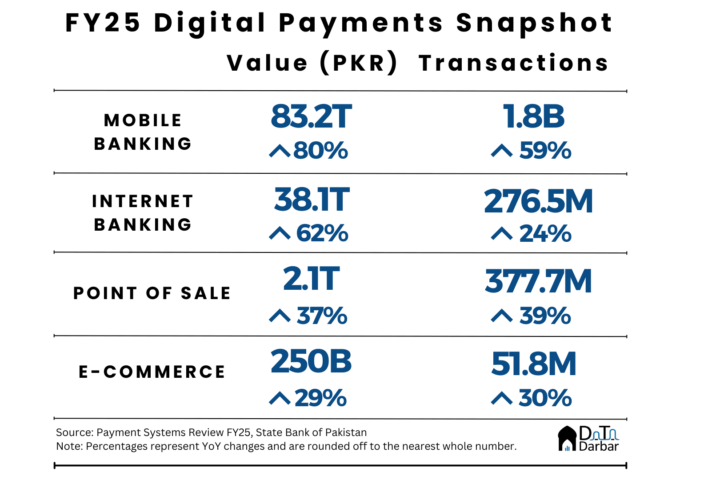

According to the industry, the MDR regime from 2020 ensured those incentives, encouraging acquirers to invest in new machines. Because they could now pocket a larger share of the commission instead of paying most of it to the issuer. It also attracted new players — including Meezan Bank, OPay, and Paymob — to enter the market. Resultantly, the number of terminals jumped from 47,567 in Q2FY20 — the quarter before the circular was published — to 104,865 in Q4FY22.

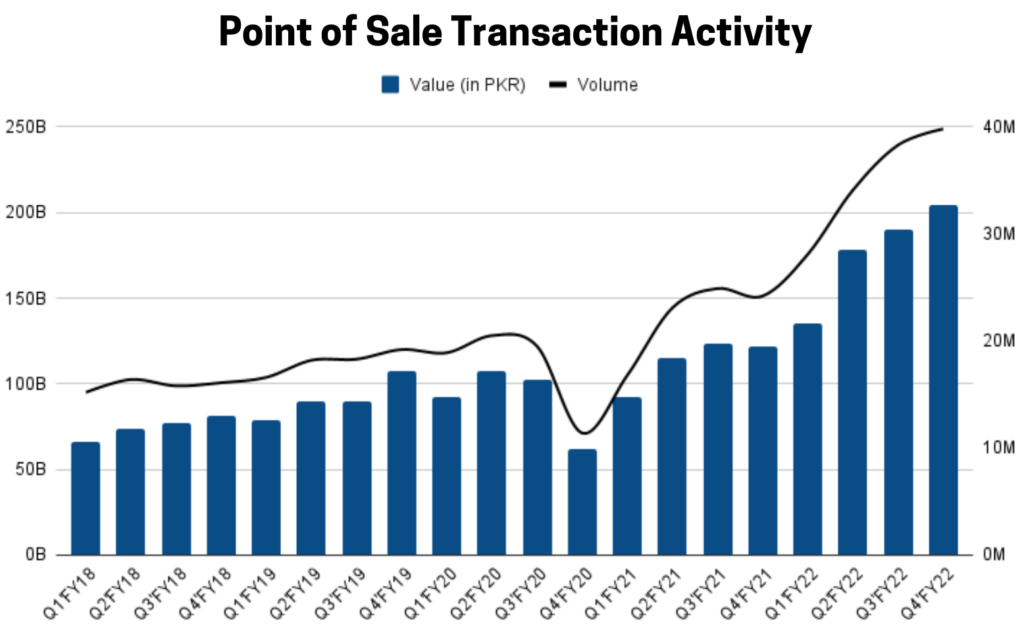

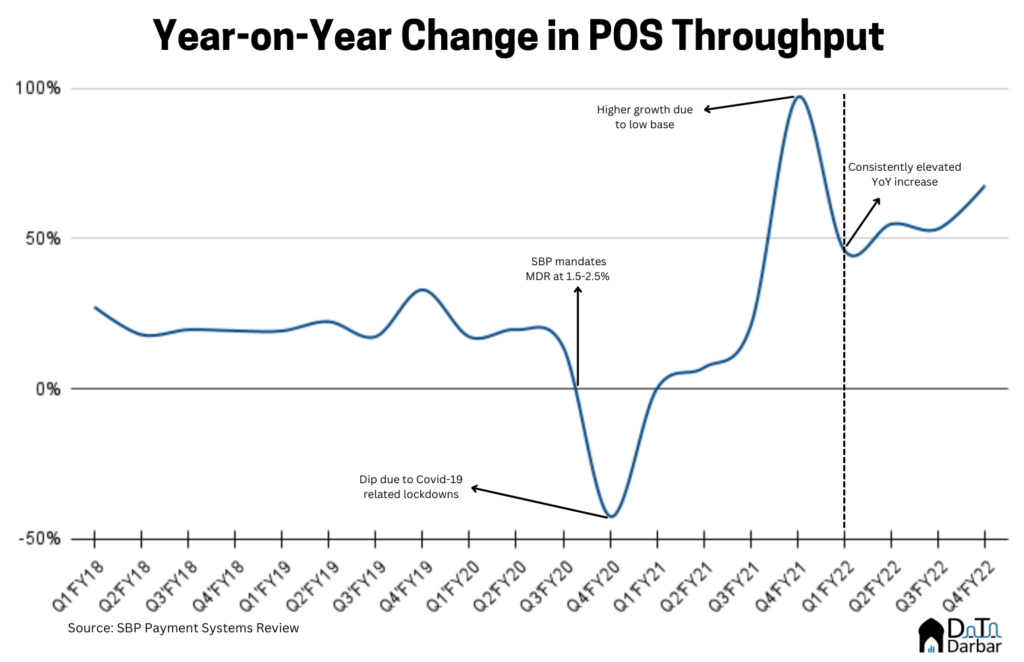

Similarly, value and volume grew to PKR 204.6B and 39.8M by Q4FY22, from PKR 107.5B and 20.5M in Q2FY20, respectively. Since the beginning of 2021 — to isolate the effect of Covid-19 — the activity has picked up further with average YoY growth in throughput at 56.64% and transactions 9.78%.

For the corresponding period preceding Covid-19 (July 2018 – December 2019), the average YoY growth per quarter in throughput and transactions was 21.48% and 4.19%, respectively. To summarize, the change in MDR regime clearly spurred the POS uptake in Pakistan. But why should there be a floor or cap? The market should determine the rate, not the regulator, no? In principle, definitely.

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it

However, as the saying goes “if ain’t broke, don’t fix it”. The country’s POS ecosystem had just begun to grow like never before (at least since FY13) so why change things? Especially considering how new players entered the market based on it, and frequent regulatory changes only discourages entrants and incumbents from making further investments. Again, in theory, there should be no floor or cap, but the industry was beginning to take off. Maybe the ends do justify the means?

As per a source, the POS industry runs on the 90-10 phenomenon: 90% of the transactions can be attributed to just 10% of the merchants. This small cluster is where the acquirers make money which allows them to invest in expanding the network elsewhere, particularly to merchants where they have to take a financial hit in the medium term.

But these big merchants enjoy considerable bargaining power and without a floor, can negotiate better terms. That means the acquirer’s margin on the 90% cluster comes down (potentially to a loss), leaving little money to expand to the less lucrative segments. Consequently, the number of machines remains more or less stagnant. Apparently, that’s what was happening pre 2020 too.

The story doesn’t end here though. With respective caps of 0.2% and 0.5% for debit and credit cards on interchange fee — the share paid out to the card issuer — the acquirer has lower expenses anyway. Therefore, the MDR should be reduced. That doesn’t sit well with the issuing side, however, because well, that’s a separate business line in itself.

So if banks aren’t earning much money on transactions, there is little incentive to issue more cards. Fair, I guess. Except that they are making enough by lazily investing in riskless government securities off our deposits. It honestly wouldn’t hurt them too much to offer some bare minimum service to the customers.

That said, Pakistan does have a high MDR, compared to for example 1% in Indonesia or 1.25% in Nigeria. It matters a great deal to those businesses who have to compromise their already thin margins. To be fair, cash is not free either, just that the central bank bears its cost.

Described the current situation… Nicely written