Ever since venture capital started flowing into Pakistan, the local ecosystem has seen polarizing debates. Basically on whether the companies being built are sustainable given their usually questionable unit economics. From unbelievably high losses to calls for investigating lax corporate governance mechanisms, the space receives a high dose of flak — both fair and unfair — that may be disproportionate to the underlying scale.

But there’s another sector that’s going through a somewhat similar situation, yet has avoided scrutiny for the most part. Except maybe a few reports in the press here and there. Pakistan’s microfinance banking has been undergoing its share of troubles the last few years. In fact, the scale of losses can somewhat mirror VC-backed businesses even if the comparison is apples and oranges.

Finanacial Red Flags of Microfinance Banks

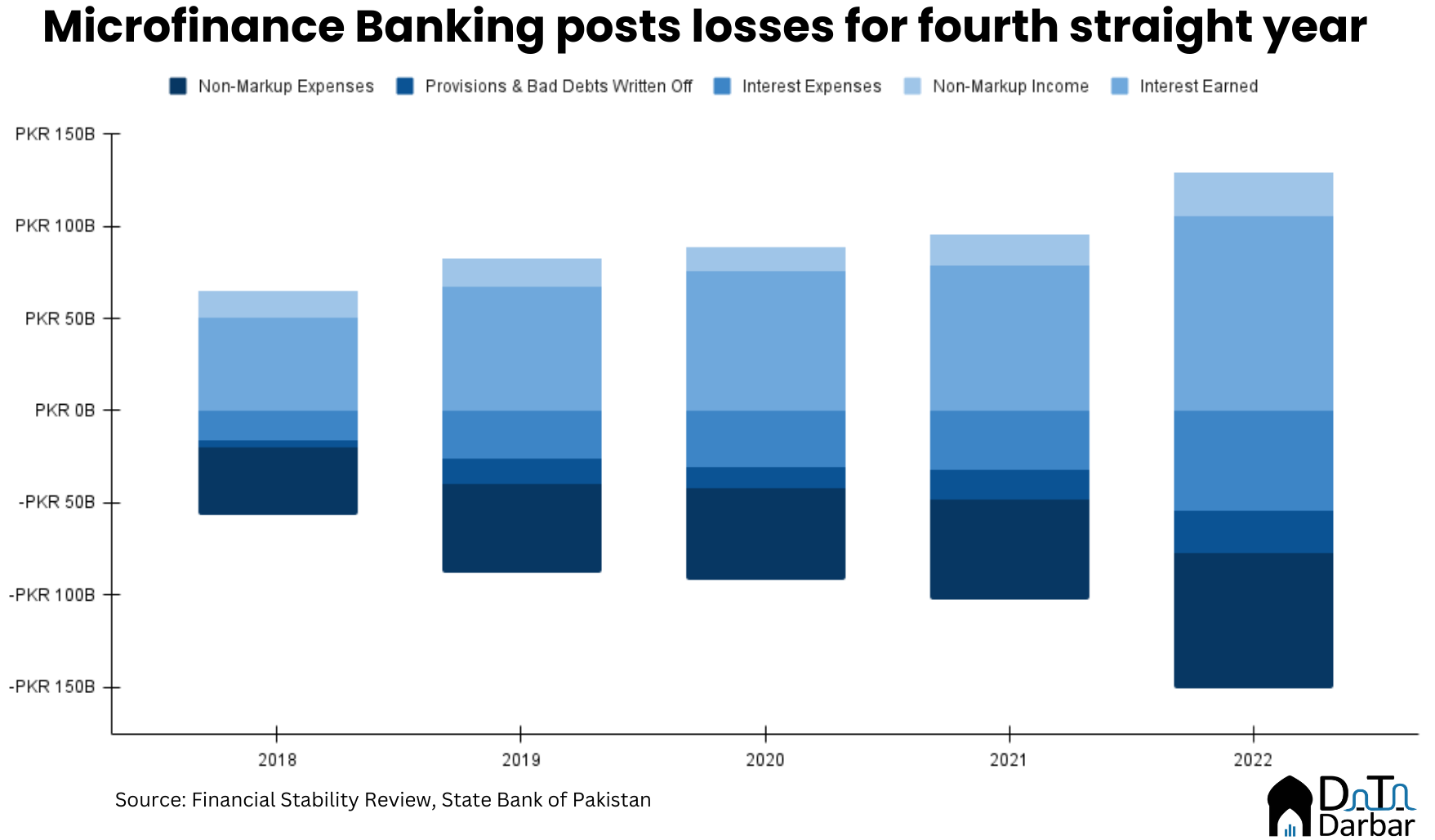

According to the SBP’s Financial Stability Report, microfinance banks cumulatively posted a red bottomline for the fourth year straight. The post-tax loss of the sector reached PKR 17.16B in 2022, significantly worsening from PKR 8.08B in 2021. While the regulator blames it on Covid and subsequently the macro deterioration and floods, the sector’s woes began in 2019.

The number of loss-making institutions increased to six in 2022 from four in 2021. For quite a while now, some of the more notable players have been relying on the largesse of their sponsors for capital injections in order to continue operations — not too dissimilar from the VC-backed businesses.

Similarly, the total capital to risk-weighted assets continued its downward trajectory for the fourth consecutive year, declining to 10.9% in 2022, from 18.3% in 2021. This is lower than the minimum mandated capital adequacy ratio for microfinance banks set at 15pc. The Tier 1 capital position has also posted a similar trend, falling to just 8.1%.

While the sector only accounts for just 2.2% of the overall banking deposits, it still holds an outsize importance due to the strong market penetration. As of 2022, there were 90.8M accounts with microfinance banks, of which 5.3M were borrowers with outstanding loans of PKR 361.7B.

Many of them have traditionally lacked access to credit and undergone serious financial stress since the onset of Covid-19 and the subsequent macroeconomic stress of the last few years, affecting their repayment ability. As a result, the sector’s gross non-performing loans ratio rose to 6.7% in 2022, from 5.2% the year before.

This shouldn’t be too surprising given the sharp recalibration in monetary policy over the last two years. One way to look at its impact is that the share of outstanding loans at interest rates of 25% or more reached 77% of the total by December, well above from just 51% in June 2022. Similarly, 15% of all credit was at 36% or higher price, compared to 5% in the period under review. Remember the benchmark Karachi Interbank Offer Rate between these two dates rose by a relatively modest 184 basis points.

Meanwhile, the sector remains under pressure from two fronts simultaneously. First, the provisioning and bad debts written off jumped by 40.1% to PKR 22.8B in 2022. Secondly, the growth in admin expenses in particular also considerably accelerated to 33.6% and reach PKR 70.8B. For context, the corresponding increase in net interest plus non-markup income was relatively slower at 19%.

Read: The Nano-ization of Microfinance Loans

Though the sector’s ability to survive without sponsors’ generosity has been questionable for sometime, the cracks are only widening now. Enough for the International Monetary Fund to take notice in its latest report on Pakistan.

“We will also continue our efforts to tackle pockets of vulnerability in the microfinance bank sector, which has been severely affected by the floods, among others by asking the owners for time-bound recapitalization plans to address existing capital shortfalls and by otherwise ensuring the orderly market exit of non-viable institutions.”

Now the question is what will the regulator do about it? If the two private commercial banks with capital issues are to serve as an example, it may be a while before any serious action is taken regarding the microfinance institutions. Especially considering how these entities help push the financial inclusion targets, particularly those relating to account opening.

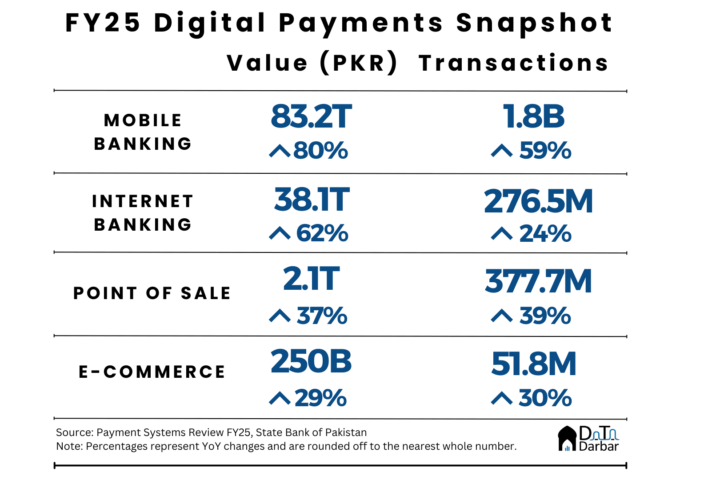

Even as (or because of) financials of MFB sector weakened, they continued the impressive growth on the payments side. During 2022, JazzCash alone did digital throughput of PKR 4.2T across 2.1B transactions. Meanwhile, EasyPaisa followed with PKR 3.9T and 1.4B, respectively.

A relatively shorter version of this article first appeared in Dawn.