For all the self-righteousness and political bickering, Pakistani Twitter can still be useful at times. We witnessed that last week when social media users highlighted how instant credit apps were exploiting and harassing people. This forced the regulator to at least look into the matter and called a meeting with relevant parties. Of course, that turned out to be meaningless as it simply told them to “self-govern”. How will that self governance work when the entire business model of nano loans is based on flawed math and a lack of transparency?

Take away this exploitation and deception, and the entire business model of nano lending crumbles. Let’s understand the economics of it to see why. For an institution to lend, it needs funds which can come from either debt or equity. That has a cost, which Finance 101 dictates is higher for the latter, for it’s riskier.

In this regard, banks are best positioned due to cheap deposits, thanks to current (free) and savings accounts (8-10%). But since the government papers yield over 15%, they simply lend to the sovereign and make healthy net interest margins. As the credit risk goes up, so does the required rate of return. This is why the likes of HBL charge up to 38% APR for certain products and customer profiles.

Breaking down the math of nano loans

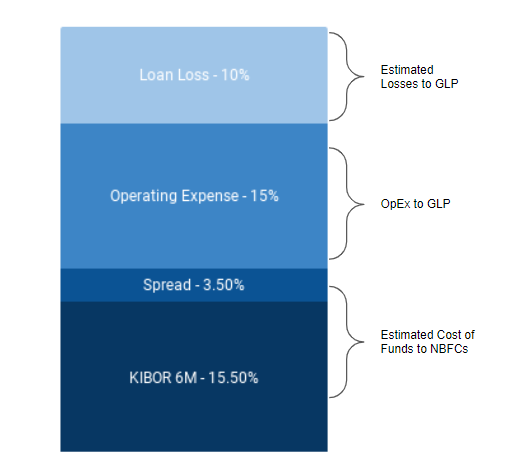

Non-banking finance companies do not enjoy the same privilege. For them, deposits are not an option and debt costs a few percentage points over the Karachi Interbank Offer Rate (6M at 15.52%). According to a note by the Pakistan Microfinance Network (PMN), that average spread to non-banks is 3.5%. So any lending has to recover that. Then incorporate a hefty premium for the high credit risk and a component for operational costs incurred, which is usually upwards of 15%.

This is usually the justification given for higher interest rates charged by microfinance banks, as a major component of the asset yield goes towards cost of operations. Basically the salaries and commissions for on-ground sales and recovery staff.

Kabir Naqvi of UBank broke down the components of microfinance loans for me in an interview last year. “Say we charge 32% annualized (asset yield) to the customer, around 12% will go towards operations. We also incur a higher cost of funding than commercial banks, so add another 12% for that. Then the delinquencies will be about 4%, which basically leaves a 4% margin for us.”

In The How and Why of Microfinance Lending Rates, Ali Basharat of PMN explains this further. “The lending rates offered by MFPs in the sector are market driven and are dependent upon several factors; such as the Funding Costs associated with the MFPs, Operational Costs and the exposure to Credit Risks.”

According to UBank’s annual report, they had 1,302 credit/sales staff in 2021, helping it build a loan book of Rs34 billion through a network of 207 branches. The general argument is that once lending becomes more algorithmic, fewer people would be required and the cost to customers would come down. Sounds convincing, in theory at least.

Building an army of agents for “digital” lending

However, this is not what’s happening in reality. One’d expect that digital lenders to automate processes. Origination and distribution-wise, they do. But in the end, they depend on recovery staff to harass and intimidate borrowers, just via phone this time. In fact, their army of agents is even bigger at times.

Sarmaya, the entity behind Easy Loan, had 2,500 agents, of which they fired 250 in the wake of misconduct reports (read: social media campaign), according to a company spokesperson. For a tech company with no branches, that is a staggering number and puts it in a similar league as some of the biggest players in microfinance.

In contrast, even Khushhali Microfinance, which has the largest loan book and 239 branches, employs 2,743 people in credit/sales. Akhuwat, an NBFC like Sarmaya, had 3,698 people in total across 791 branches. These are primarily brick and mortar businesses. Compared to more tech-centric players like Jazzcash or EasyPaisa, Sarmaya has a higher agent headcount than the other two’s employees despite them having 105 and 66 branches, respectively.

That brings us back to the conventional wisdom propagated by digital lenders on the potential of technology to make borrowing affordable. Sure, you can lend online instantly but if recovery is entirely dependent on an army of agents, how will the costs decline? There is a trade-off. You can automate and reduce operating expenses but loan losses will spike. Quality data and better credit models can theoretically ameliorate this problem but when the key players’ model relies on deception, it’s not going to change anything.