Pakistan’s fintech is obsessed with digital wallets. It’s the first (and often the only) innovation that many founders come up with. The idea is to ‘reimagine’ payments by providing customers with a sleek interface and a nimble experience. SimSim and Keenu were the earliest players to enter the market with this promise in late 2016 and early 2017, respectively. And for the next couple of years, the only two. That was until the State Bank introduced the Electronic Money Institution (EMI) Regulations in 2019.

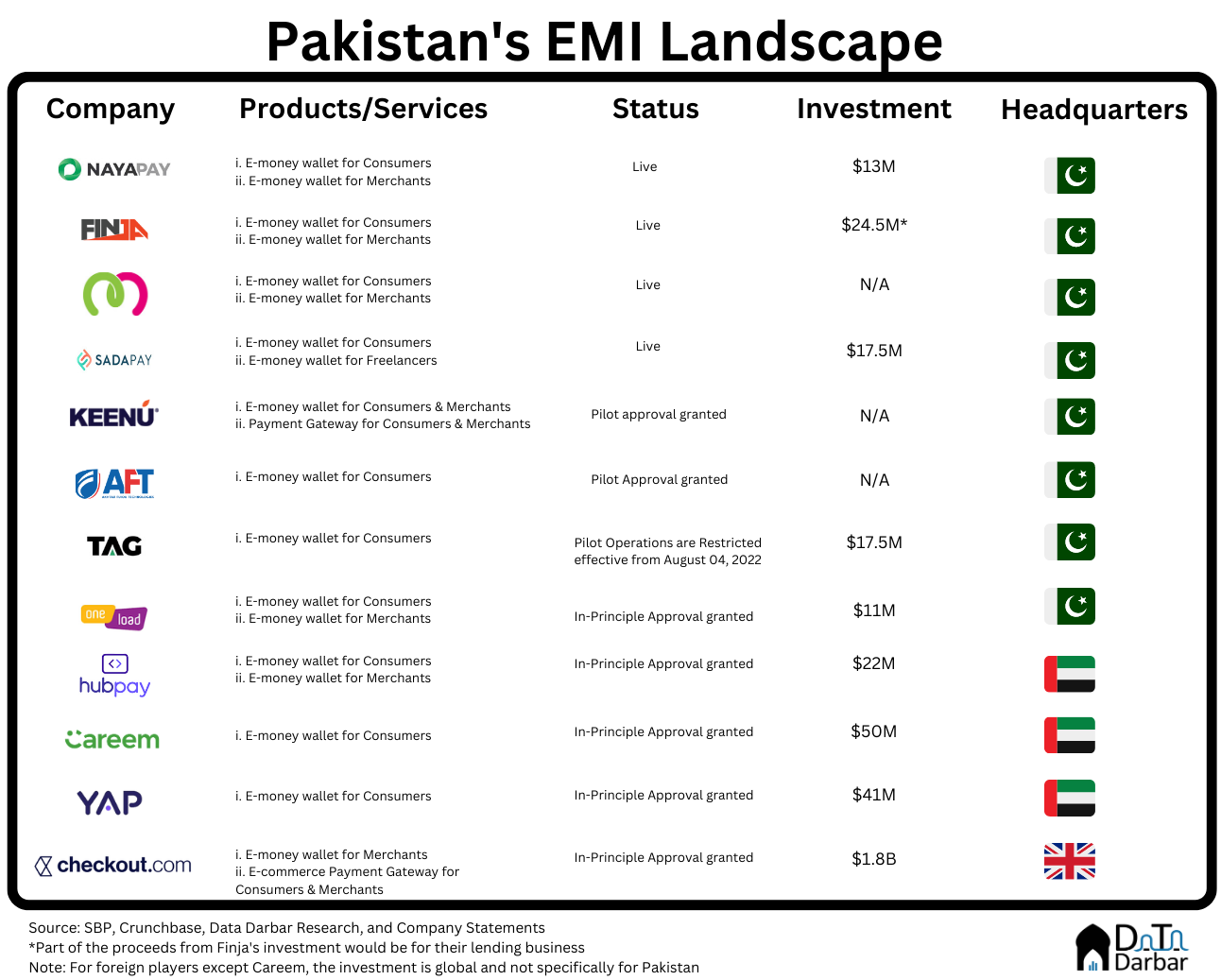

The new regulations made it possible for fintechs to open digital accounts themselves and bypass banks. Well, almost. They still needed to rely on a partner bank for settlement but could now independently offer three services: transfers, bill payments and mobile top-ups. Thus began the love affair with EMIs, for which 12 players have received some form of approval from the SBP. [Note: TAG’s license was, however, revoked in October.]

That includes both Pakistani players as well as those looking to enter the local market. The former alone have raised around $134 million already, including Careem’s $50M announced allocation. Add to it the likes of HubPay or YAP and you are looking at $62M of additional capital without factoring in Checkout. This makes EMIs one of the most competitive spaces in the startup ecosystem.

But what makes them so popular? After all, their mandate is limited to just payments – something that’s widely believed to not make much money in the absence of other products like lending. Admittedly, Pakistan is primarily a cash-based economy with currency in circulation of Rs8.19 trillion, or almost 20% of GDP. That means there is plenty of room for further digitization.

Understanding the Business Model of Digital Wallets

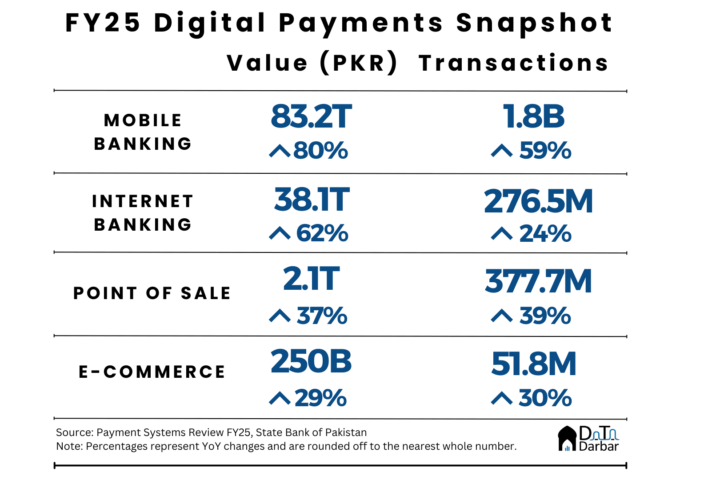

Indeed, but the problem is that the payments market is already too saturated. When Keenu and SimSim started off, banks had barely functioning apps and the overall mobile banking stood at just Rs21B across 1.2M transactions. Now, between banks, EMIs and Payment Service Operators/Providers, there are around 50 entities vying to provide the same offerings, with the former alone doing over Rs3T a quarter through just mobile banking. Some of the biggest banks have Digital vs OTC transaction mix exceeding 80-90%.

When all players are competing for customers’ deposits, such fragmentation chokes one of the main revenue streams. Which brings us to the monetization channels in payments. Primarily, there are two: float and service fees. The former is basically the interest income earned over 50% of the average last three-month deposits and the latter includes charges on bill payments, transfers etc.

In order to make money off float, total deposits held by a company need to be absolutely massive. There are two ways to get there: either have high average balance or huge volumes. We can start out with the former as its data for branchless banking and scheduled banks is available.

For branchless banking, which includes Jazzcash and Easypaisa, the average account balance stood at only Rs832. Given that EMIs are technically very similar in terms of the offering, even more limiting actually, their numbers should be similar. To work upwards, say a fintech has one million customers, the total amount held would be Rs832M. Of that, only half, i.e. Rs416M, can be invested to earn deposits at the prevailing interest of around 10% annualized. That would yield them Rs41.6M in income – barely enough to cover the cost of its executives.

Now, one can argue that the average balance in branchless banking is too low for they target low-income segments. That is unlikely to be the case with EMIs who are more focused towards relatively well-off urban millennials. Leaving aside the philosophical aspect of this (considering that all players have been talking about expanding financial inclusion), we can turn towards deposits of commercial banks for a more comparable number.

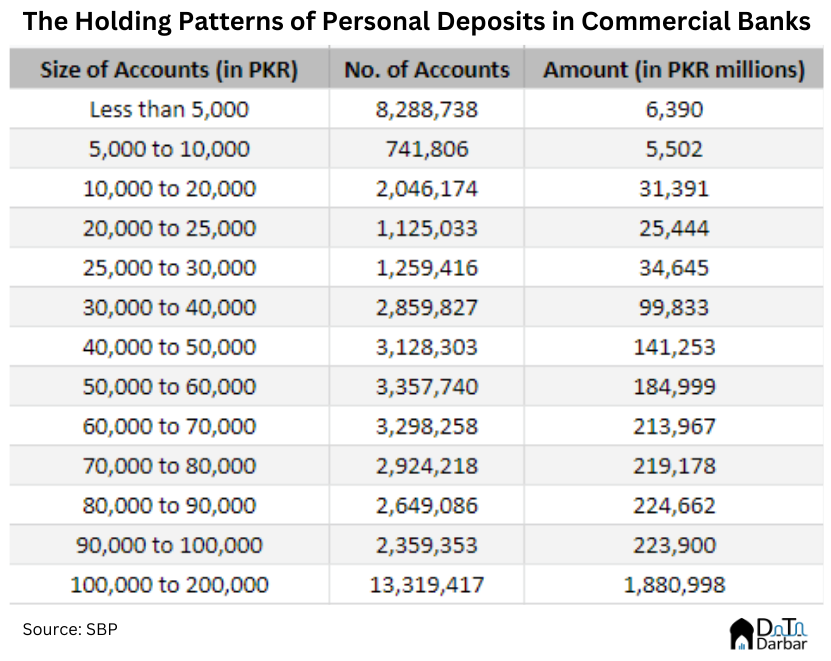

As of December 2021, these entities held over Rs9.4T in deposits across 58.1M personal accounts, meaning an average balance of Rs162,564. But that’s not apples to apples, given the EMIs have an upper limit of Rs200,000. Based on this filter, only Rs3.29T of deposits but 47.36M accounts still, hence an average balance of Rs69,517. The truth is somewhere in the middle of this and that branchless banking number, more skewed towards the latter.

Only in the overly optimistic best-case scenario is the revenue from deposits significant, though it still ignores the cost of user acquisition. According to Tellimer, CAC for Indian fintechs at large was $17 and around $45 for payments players specifically across the emerging markets. Assuming Pakistani EMIs stand well below this, say $10, that cost to acquire the million customers is going to be $30M. In addition, there will obviously be infrastructure and compliance costs as per the regulations. With help from AlphaVenture, we built a basic financial model* to help you understand the underlying math. It contains the worst, baseline and best cases as per our calculation but play around with your assumptions.

For now, we have ignored admin and other initial expenses such as licensing. The latter alone dictates that EMIs spend years waiting for regulatory approvals and earn no revenue. Meanwhile, the costs are fairly high as they need to set up compliance, dispute resolution and various other departments. There is another revenue stream too: the service charges on transactions, which we’ll talk about in the second part.

*Assumptions:

- We have taken average balance from the personal deposists held at banks, as published by the SBP here.

- For simplicity, we have assumed deposits will stay in the wallets for the subsequent three months.

- Investable money is 50% of the previous 3-month deposit balance.

- Exchange rate is from the interbank market and will update whenever there is a movement.

- We took Tellimer’s estimates on CAC and servicing and made some adjustments for Pakistan.

Excellent analysis and insight

Excellent piece!

Good food for thought….to run any business revenue is needed and there is no free lunch and if we really want to digitalized then considering benefits and costs associated. Government also has to design policies which help in digitization…..see how Afghans are converting their money in dollars in Pakistani markets and we are left with no dollars for basic needs like holy pilgrimage, education, paying to SCHEMES (UPI, VISA and Masrer) for spend by Pakisrani via Pakisrani issued cards, salaries to foreign embassies etc.

Im a digital product professional and im impressed to see these figures. Its very accurate. Please do this for the 5 digital banks entering Pakistani market.

There is a 3rd revenue stream as well, though no one has figured out in Pakistan how to create a business model around it, let alone monetize. It is to monetize customers’ transaction data. The whole model of ‘free’ payments is based on the premise that the fintech will be able to use the transaction data to build other services which will be profitable. I am not talking about selling customer data dumps for spamming. The expectation is that fintechs (EMI/BB) will be able to build a persona of its customer based on what it sees through the transaction data and then provide other related services (financial or non-financial). In Pakistan, the model by the founders is to focus on direct revenues like transaction fees. As you wrote, for a cash-dominant culture, cash will always beat digital in being ‘free’. The other way to sustain a free payment fintech is to develop a service like Zelle, which draws its revenues from the banks it serves rather than customers. I think there is room for such innovation in Pakistan. What do you think?