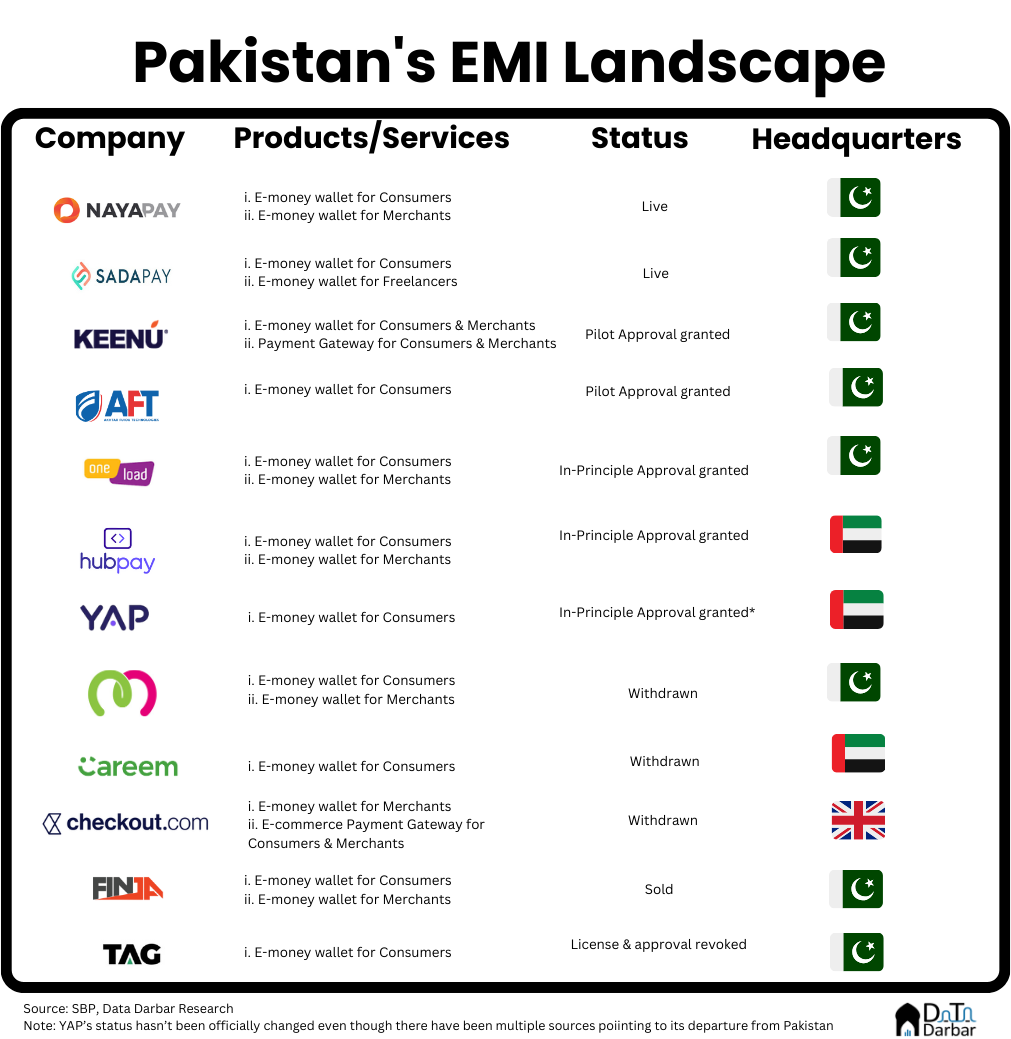

Last week, Sadapay announced to have integrated with Apple Pay and GPay, which would allow Pakistani freelancers to get their money directly. It’s a pretty solid and exciting product, according to those who have used it. But in the broader industry, things aren’t that well with an ongoing exodus of the Electronic Money Institution (EMIs). At its peak, there were 12 entities with some form of approval from the SBP. Half of them are gone now.

First, TAG’s license was revoked on account of fraud, while YAP reportedly exited Pakistan rather quietly. More recently, Finja sold its EMI to OPay amid a decline in implied valuation, shortly after Careem and Checkout withdrew their applications. Now, CMPECC (PayMax) has joined the list, becoming the first commercially live entity to abandon the business.

For anyone who’s followed our work on EMIs, this may not be surprising. Ignoring the business risks in Pakistan, it takes way too long to get the license, and even then, there are plenty of restrictions. You can only do payments, which is generally considered difficult to make money off, especially with a free gateway like Raast.

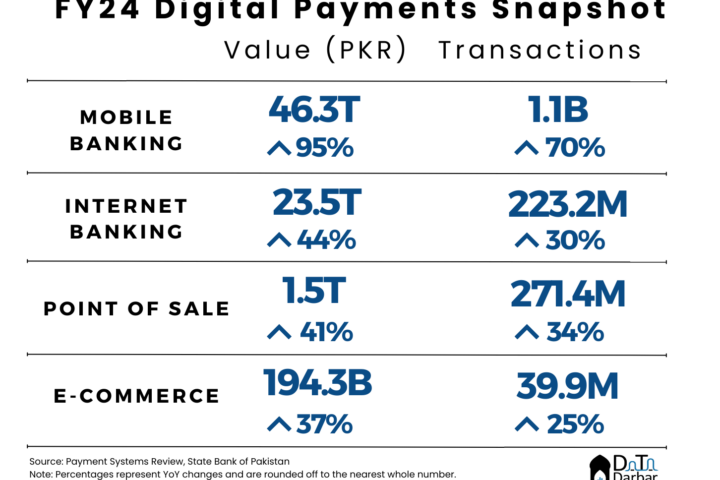

Notwithstanding the exodus, the two players that are still serious — Nayapay and Sadapay — have done decently well. According to the State Bank of Pakistan, EMIs processed a throughput of PKR 222.2B across 81.5M transactions in FY23. Clubbing the numbers annually doesn’t give sense of the incremental growth, so let’s look at quarter-wise data.

Initial traction

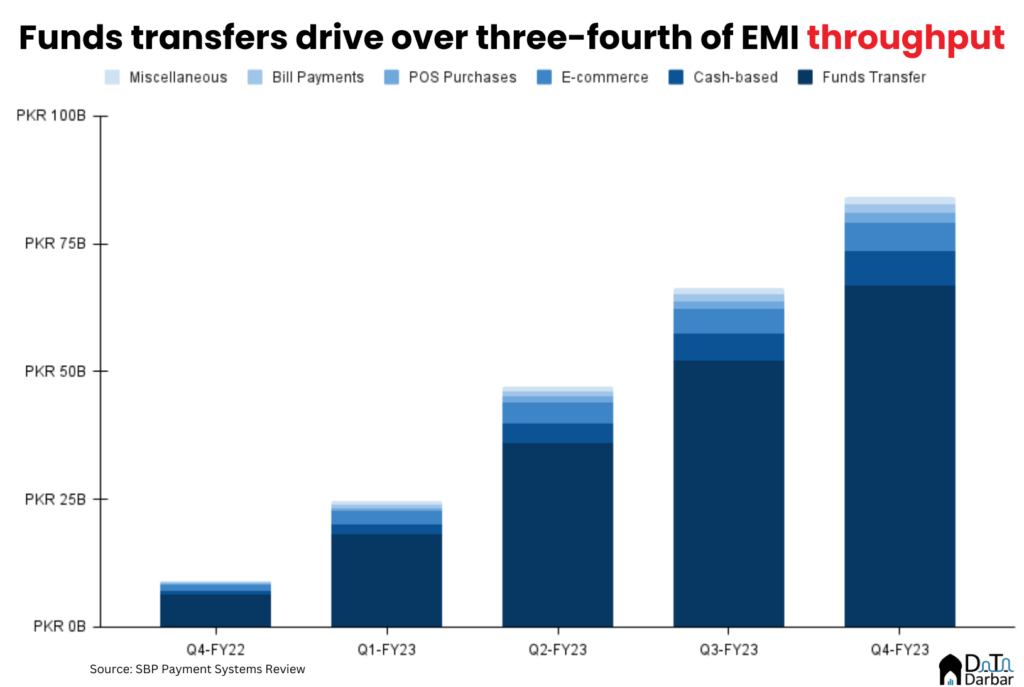

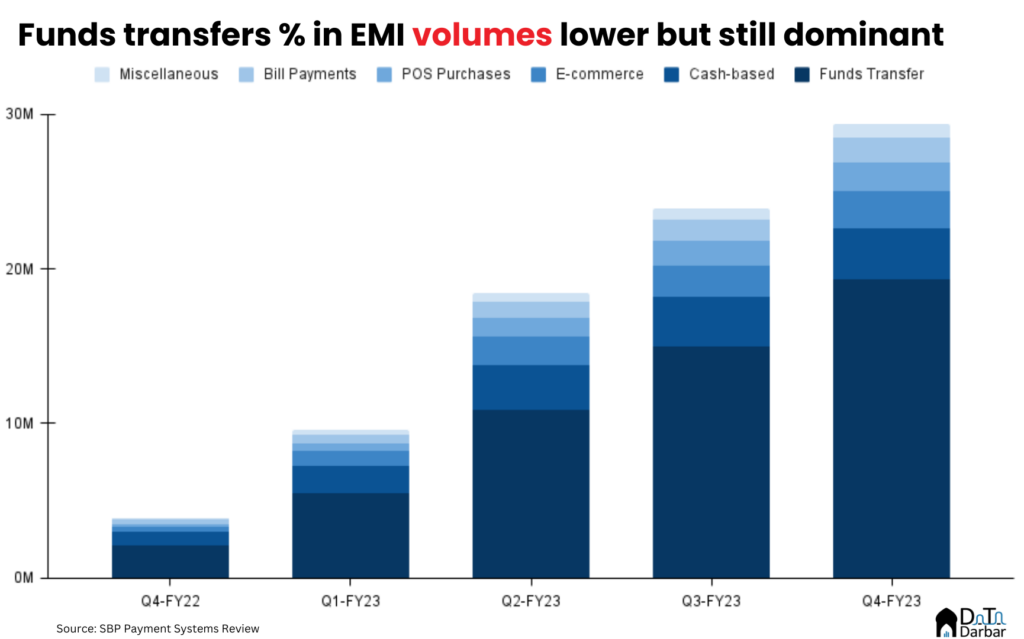

In Q4-FY23, EMIs processed 29.5M transactions worth PKR 84.1B, surging from 3.9M and PKR 9.1B, respectively. Basically, the volume has grown by 824% YoY and value by 656%, albeit off a low base. While the numbers are still quite small, they are meaningful at least.

Understandably, funds transfers were the biggest component, accounting for 77.9% of value and 62.4% of volume in FY23. Both shares have only increased with every passing quarter. More interestingly, cash transactions had the second-highest share of 7.97% in throughput. Since the start of this year, cash-based value has outpaced e-commerce and point of sale. This is telling of a broader problem as digital payment channels aren’t accepted by merchants, prompting customers to withdraw hard currency for their purchases.

Volume-wise, e-commerce had the second-highest share at 13.8%. EMIs processed 11.2M transactions, which is already over a third of what banks did (31.8M) during FY23. Admittedly, the gap between the two in throughput was much wider, with the former doing PKR 17.3B and the latter PKR 142B.

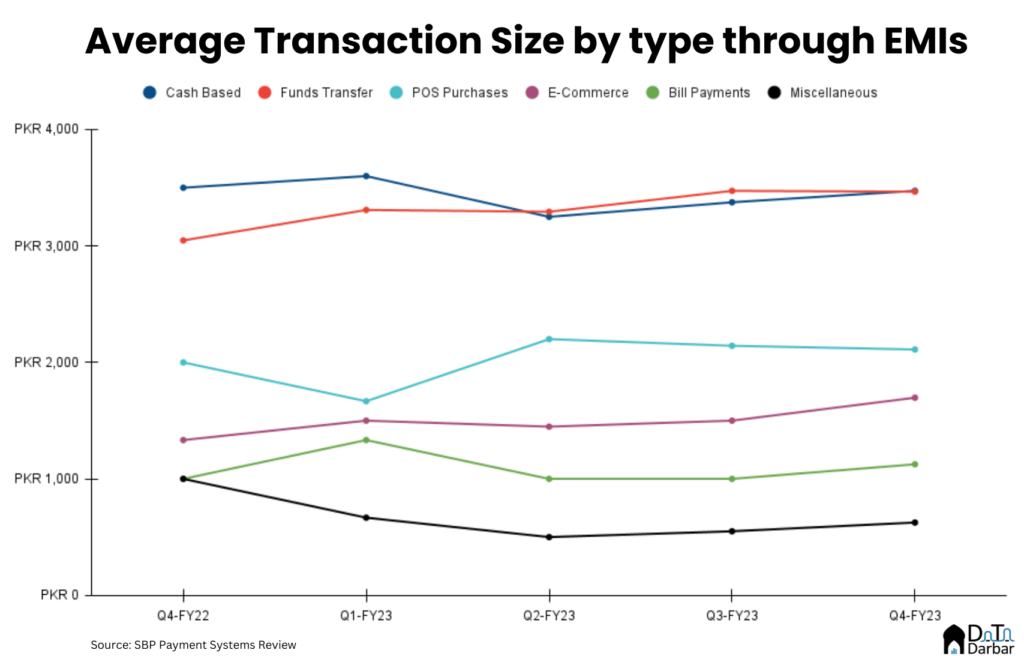

Transaction mix

Consequently, the average transaction size of EMIs in e-commerce was just PKR 1,697 during Q4-FY23, much lower than banks’ PKR 4,598. This could possibly be because people are paying for their smaller ticket online purchases — like Foodpanda and Careem — through digital wallets while using normal accounts for relatively bigger items. This difference was much bigger in funds transfer, where the average transaction size through EMIs in Q4-FY23 was just PKR 3,466. In contrast, the corresponding value for banks (mobile) stood at PKR 42K.

Meanwhile, the number of e-wallets of EMIs reached 2.02M by June, growing by 1.65M over the last year. Similarly, the total cards issued by them stood at 2.83M, compared to ~515K as of FY22 end. This includes both the physical and virtual cards, so there will be high duplication in terms of users. But let’s put this number in context. During the same period, some 37 banks and microfinance banks combined issued 3.7M debit cards on a net basis while practically 2 EMIs managed to do 2.3M. Put another way, the nascent industry now accounts for 7.7% of all debit cards in Pakistan as of June.

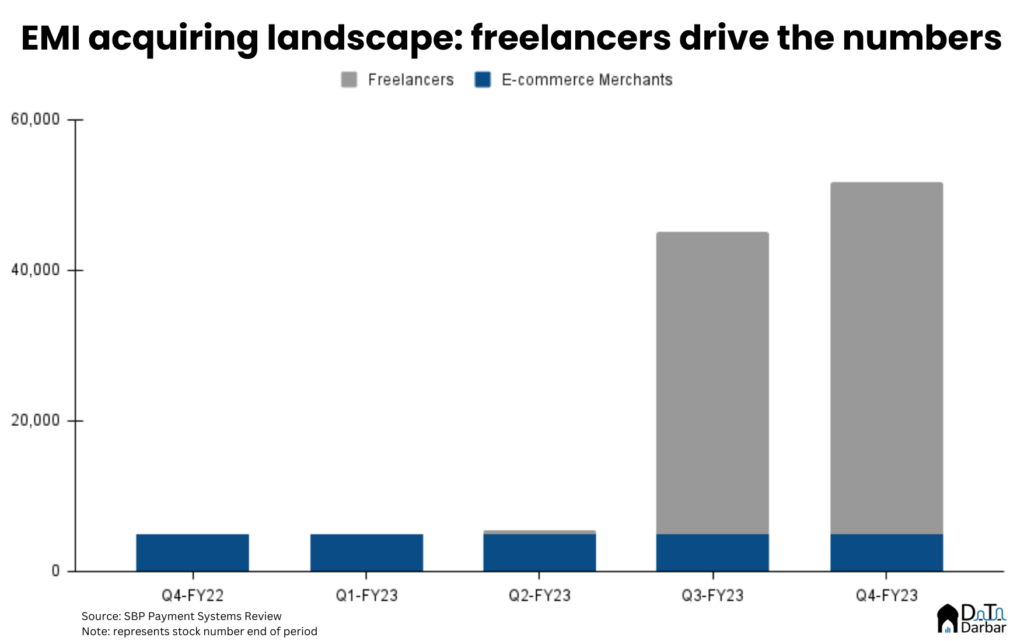

On the acquiring side, the picture was a little mixed. Total e-commerce merchants onboarded by EMIs stood at 4,956 as of FY23, essentially flat over the last year. However, there was massive growth in freelancers, which reached 46,809 by June, despite launching during the second quarter of the fiscal year.

The regulatory makeover

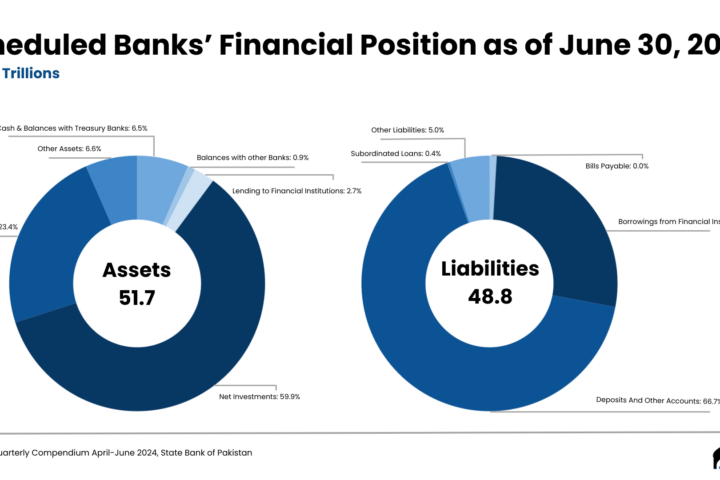

The credit for this goes to the SBP for revising the EMI regulations and addressing some of its key restrictions. For example, the transaction limit was doubled to PKR 400,000 for customers with biometric verification, with an option to further enhance to PKR 1M in certain cases. Moreover, it expanded the scope of allowed activities.

Under the revised regulations, EMIs can now offer services like escrow for e-commerce, payments aggregation, and APIs to other financial institutions. This blurs the line between EMIs and PSO/PSPs, as some of the services previously came under the latter. And that’s why the PSO/PSPs can now upgrade their license to EMI after fulfilling the necessary requirements.

Additionally, EMIs can do cross-border payments. While this opens up the freelancer segment, there are a few caveats. First, the disbursement of inward remittances has to be in PKR, meaning the customer can’t store the amount in USD. That’s not a good proposition to anyone making dollars. Secondly, this product has to be offered in partnership with an Authorized Dealer i.e. one of the 31 banks pre-approved by the SBP to deal in foreign exchange. For this use case, the limit can go up to PKR 1.5M, subject to approval.

While these changes will help expand the size of the potential customer base and their value, the revised regulations also allow EMIs to make relatively more money off that. They can now invest 75% of the last three month’s average balance over the last three months’ daily average outstanding balance in government securities with maturity up to a year, compared to 50% previously. Yay, more money for the Ministry of Finance!