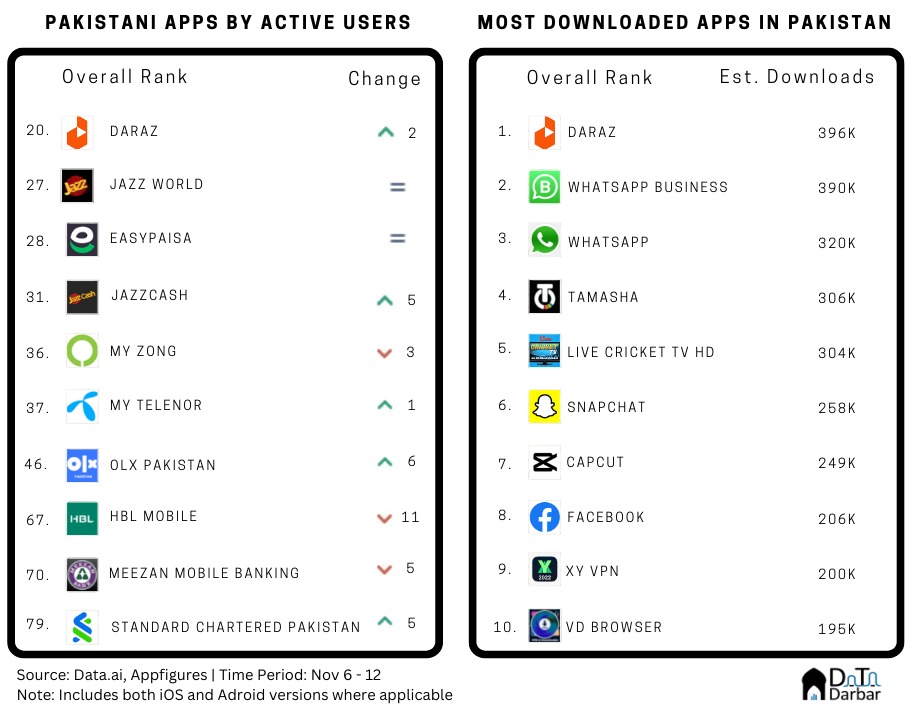

Welcome to the eighth edition of Appistan. In the last issue, we explored the evolving audio streaming habits of Pakistanis, from jumping in on the Patari bandwagon (and then abandoning it just as quickly) to finally using Spotify legally after years of APK & VPN exchanges. Now to newer things: Daraz retained its top spot among Pakistani apps on Data.ai’s active user rank during Nov 6-12. This was an improvement of two notches to reach 20th place – the best place for a local platform since we started tracking the rankings. The list remained the same overall even as there was a slight change in order. Downloads-wise too, Daraz reached the top spot for the first time since we started tracking it. With an estimated 396K installs between Nov 6 and Nov 12, the app had a double whammy working in its favor: the overlap of November sales season and the cricket world cup. A new name, XY VPN, also made it to the top 10. For the second part of the newsletter, we dive into the ever-expanding (and replicating?) edtech space in Pakistan, its evolution post-Covid, and the players competing for the top spot.

Covid, Education, and Technology: how the turntables

Up until the mid-2010s, it was unimaginable for students to carry mobile phones in schools. Back then, electronic devices were invariably considered distractions, and rightly so (kinda). The internet was a pastime, and the only time you could access it in school was during computer lab hours when everyone excitedly huddled around one computer with an excruciatingly slow and spotty connection (not much has changed in that regard though) to play Miniclip games.

Come Covid and everything changed. Educational institutions faced an existential crisis – adopt technology or die. The choice was pretty clear. As was the opportunity for edtech founders who had been toiling for customers for the past few years. All of a sudden, they had healthy pipelines as everyone wanted to finally test their products.

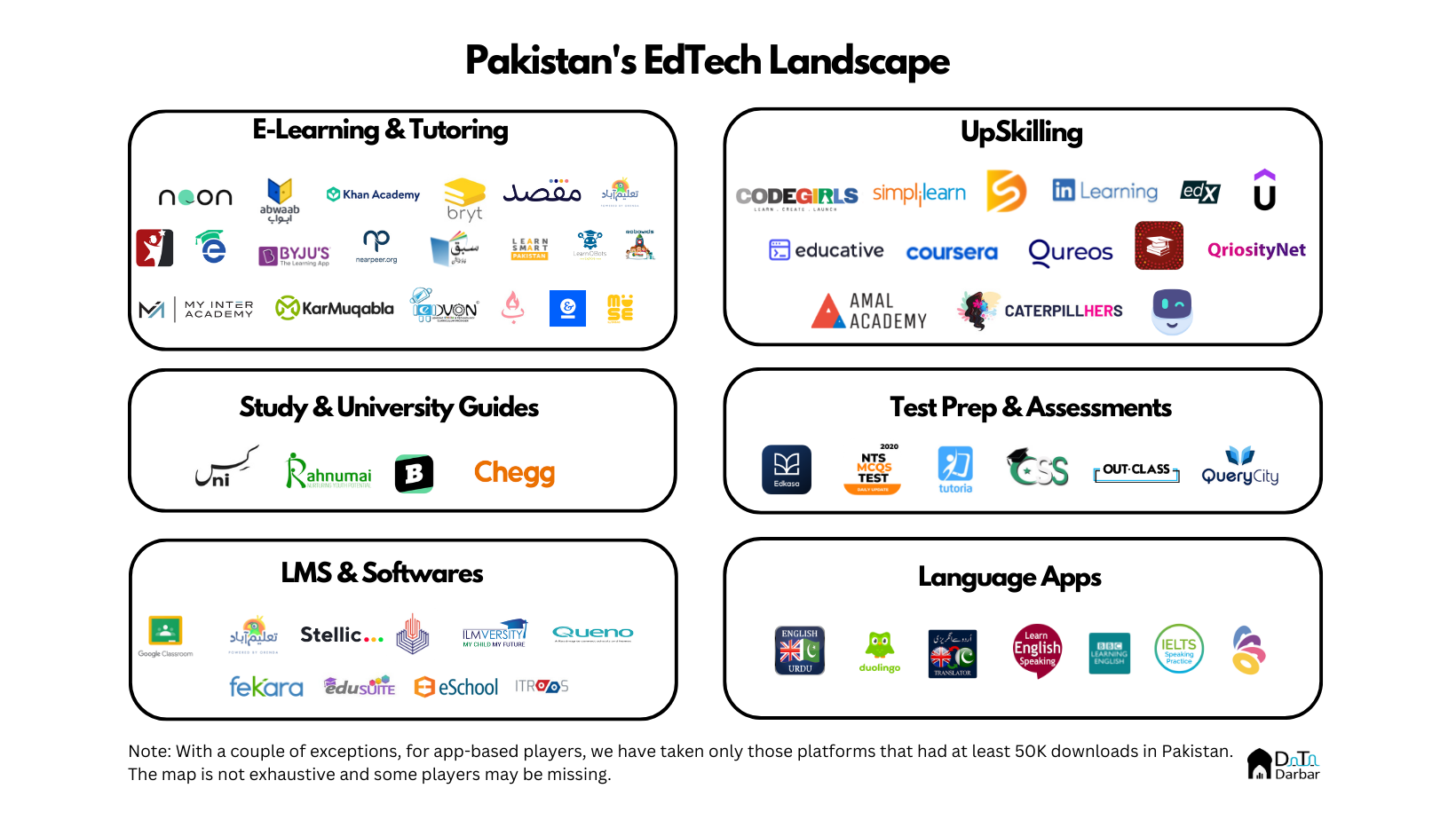

That encouraged many new players to enter the market, which finally seemed ready for innovation. In fact, four of the five most popular edtech platforms in Pakistan were launched post-Covid. Overall, Pakistanis downloaded education apps (see market map) almost 27M times, overwhelmingly after the pandemic. For example, Google Classroom had cumulative installs of 170K in Pakistan between Jan’17 and Feb’20 – i.e 26 months. Then in Mar’20 alone, it saw the number jump to 240K and has since done another 2.5M.

But before they were a thing, it was a local player that tried to sell software. In 2015 (what feels like an eternity ago), MySmacEd announced raising funding for its LMS at a valuation of $2M. At the time, you could count on your fingers the number of platform-based companies in Pakistan. Anyway, they closed shop soon after… because it was 2015. 4G was a novel concept; tracking your child’s schoolwork was still done the traditional way (notes pinned to their uniforms or written in diaries) and there were only a handful of parents/schools that cared about digitizing this aspect of education delivery.

E-learning’s rise to the top (of Play Store)

While MySmacEd may not have survived, it paved the way for others, like Queno and Ilmversity. But it wasn’t software where the biggest names of edtech were made. That mantle belonged to e-learning startups specializing in content. It started with Taleemebad in 2018 and The Learning Pitch soon after, but the scale really took off post-Covid with the entry of newer players. With discounted (or free) catalogues, sometimes promoted by cricket superstars, it’s no wonder the downloads shot up.

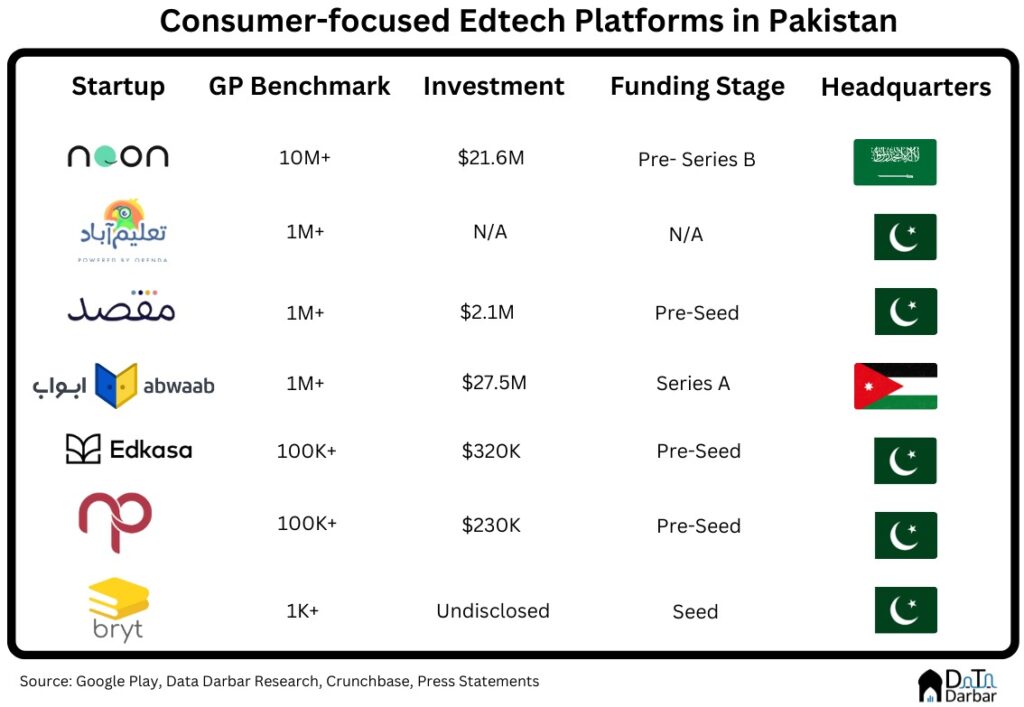

This was a direct result of market exuberance, thanks to rallies in stocks encompassing the ‘remote’ theme, which found its way into the VC industry. Pakistani edtech startups managed to get a small share of that, with 10 deals in the sector since 2020 – though worth only $3.9M (out of a total of $6.2M). However, that understates the true investment for multiple reasons. First, it doesn’t account for money spent by regional players in the local market. Second, it ignores startups with human capital (and co-founders) in Pakistan. While it’s difficult to estimate the former, the latter is easier. Educative, Stellic, and Queros — three companies headquartered abroad but with strong links to (and operations in) Pakistan — have cumulatively raised $31.9M as well. Beyond that, many major institutes also undertook digital transformation projects.

Anyway, downloads-wise, Saudi-headquartered Noon leads the way with 5M installs since its launch in Pakistan. Taleemabad also does well, especially considering it has never raised any external money (except for the GSMA grant). Lately, it’s Maqsad that’s dominating the top charts on Google Play, recently crossing the 1M downloads barrier.

The ranking changes if we broaden our edtech lens to include apps like Duolingo, Chegg. While ~1.8M may be a drop in the ocean for Duolingo and even surprising given how persuasive (read: annoying) the Duolingo owl is, language apps make up a good chunk of downloads in Pakistan. Although I am still curious as to why so many people are learning French. Is placing an order at Cafe Flo really that hard?

The Next Frontiers of Edtech

There are quite a few education apps focusing on test prep as well – from civil services to university entrance exams. While the list includes Nearpeer — which recently raised money from SOSV — (plus Noon and Maqsad), it’s actually small software houses that are leading in this space. That said, no one has really reached a meaningful scale, even in terms of downloads, let alone users.

This brings us to the next part (and problem) in edtech, particularly the consumer-oriented segment. Monetization is quite tricky. First, content is extremely expensive to make and even harder to distinguish from. After all, the internet is full of basic science and math concepts videos. So how do you get a user (that too a dependent kid with barely any pocket money) to pay for something that they can get for free with just a bit of effort?

Noon has attempted to solve this problem by promoting what it calls social learning. It on-boards prominent faculty, with a pull factor, and allows students to interact with both teachers and their fellows to sort of simulate the in-person experience. Maqsad has also tried to gamify the experience, with a points-based system using the carrots and sticks mechanism.

Of late, there has also been some interest in upskilling platforms, like Coursera and LinkedIn Learning. However, it’s still a greenfield as far as truly local players are concerned (Queros is Dubai headquartered). In any case, given the state of education in Pakistan and our performance on various indicators, no amount of money or players is enough to fill the gap. Not yet, at least.

Good job! Honestly, EdTech is literally the way forward. I did CS50 from Harvard University 24 hours long course on Youtube completely free. Internet can teach you a very valuable skill in no time and ready-made you for job market especially remote jobs in software and design field.

Can someone please explain what GP benchmark stands for?

Thank you