Imagine it’s 2021. Whenever you open social media, some regional startup or the other has announced raising funding, which they often claim to be the biggest in that particular geography or stage as well. There’s optimism all around, which gets a steroid injection after Swvl — considered to be MENAP’s biggest success story after Careem — has announced plans to list on NASDAQ after merging with Queen’s Gambit Capital in a special purpose acquisition company transaction, the hot thing at the time.

On Apr 1 2022, the company made its debut on NASDAQ at an initial offer price of $9.95, yielding a market capitalization of $1.5B. “Expected proceeds from the listing will total $640 million, including $160M in immediate capital and $480M over the next few weeks if certain closing conditions are met” Swvl’s Chief Financial Officer Youssef Salem had said in a press statement.

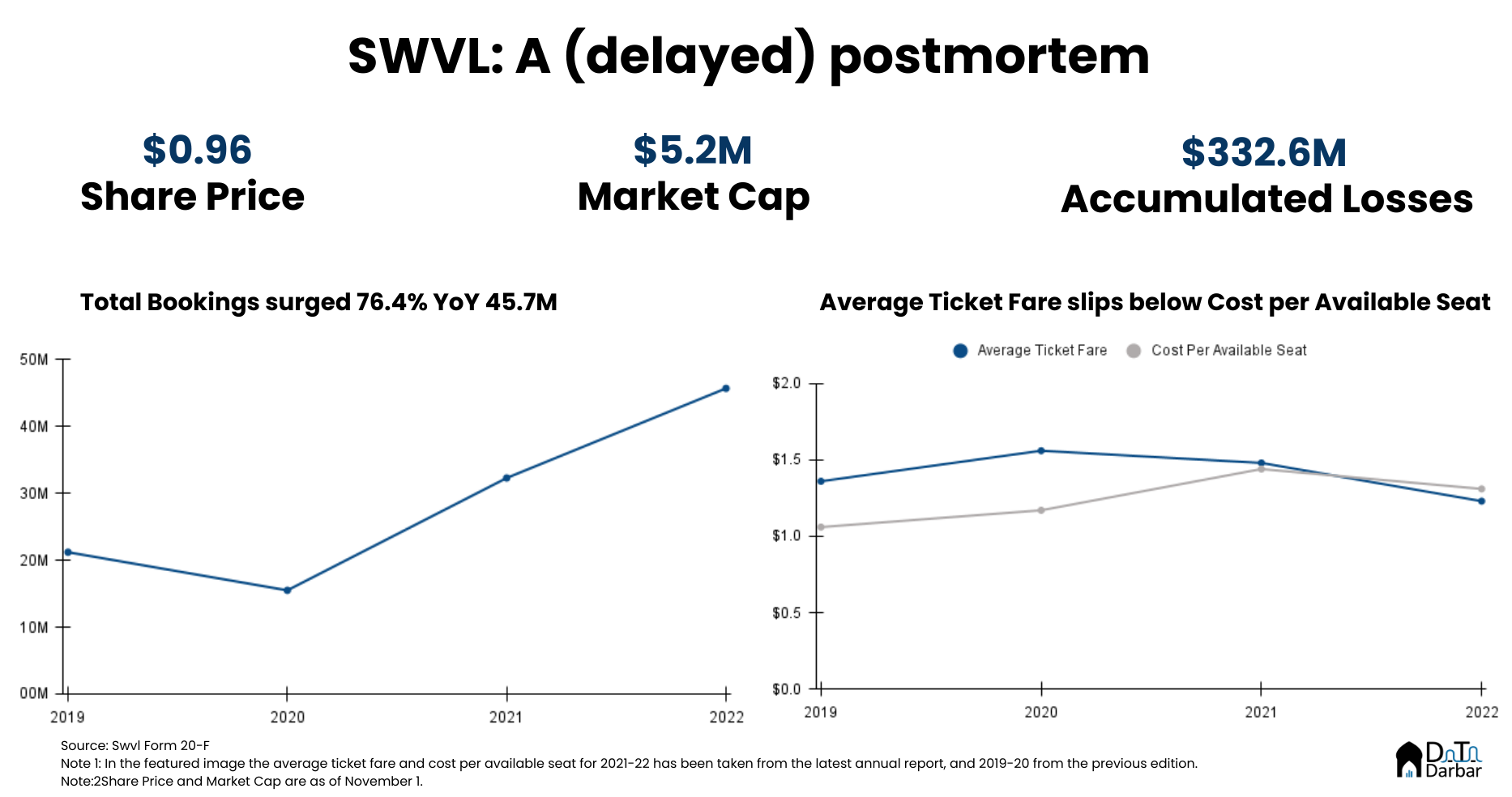

But the past is another country. Today, Swvl’s total market cap is a mere $5.13M with share price of just $0.95 on Oct 31. The company didn’t even have enough money to pay an auditor for its 2022 annual report. But after a delay of six months from the original deadline, the document is finally out. As expected, it presents a pretty grim picture of the underlying financial position of one of the most capitalized startups in the region, or even globally. If anything, that picture is not grim enough as nine more months have passed since then and things have probably turned for the worse.

The Report Card

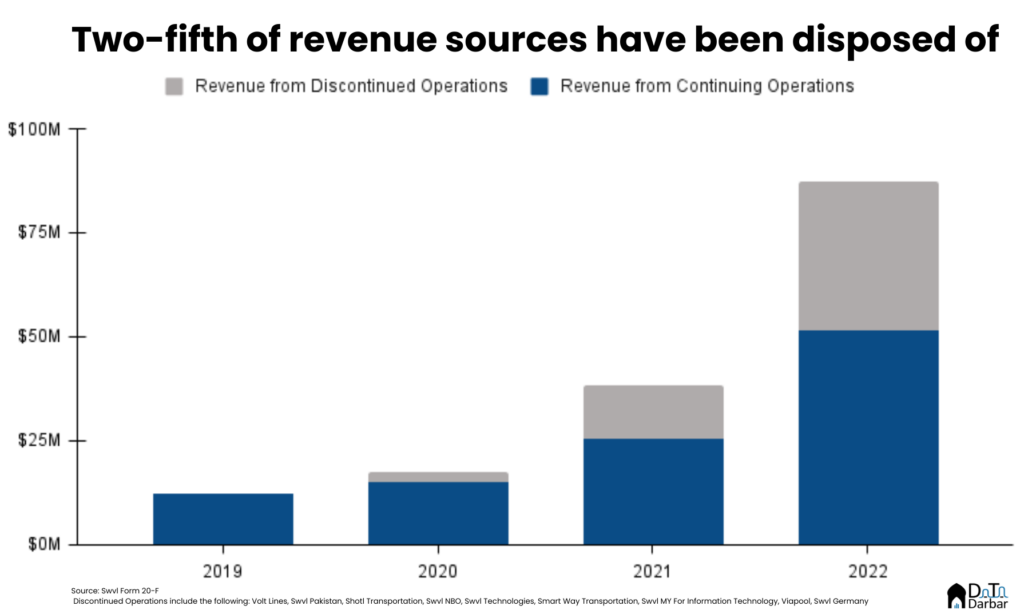

As outdated as the annual report may be now, let’s revisit it to see how Swvl unraveled. In 2022, the company recorded revenue from continuing operations of $51.5M, up 101.4% over $25.6M the previous year. This helped push the gross income into black for the first time at $2.8M, from a loss of $5.8M. Meanwhile, markets contributing $35.74M have been disposed of.

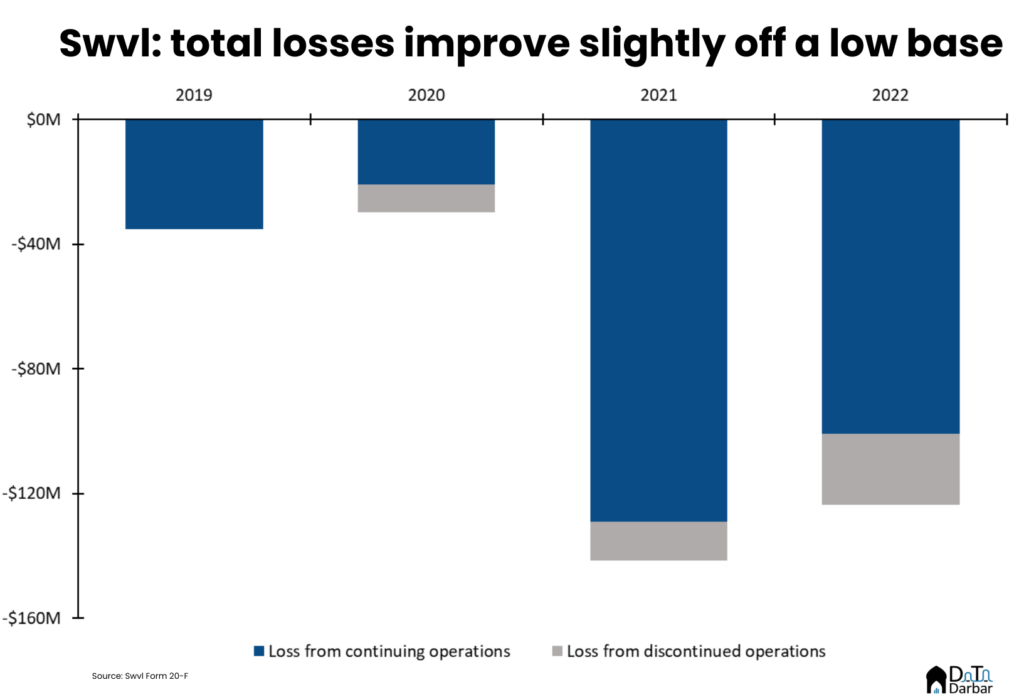

Does that mean Swvl was on its way towards a more sustainable unit economics? Well, not quite. Despite mass layoffs and pullback from major markets, the company’s selling and marketing costs surged 48.9% to $18.1M while general and administrative expenses edged lower to $66.5M. As a result, operating loss improved slightly to $82.4M in 2022, from $88.1M the year before.

However, amid heavy recapitalization costs of $139.6M, Swvl’s loss from continuing operations in 2022 was $100.96M. While one can consider this an upgrade from $129.1M the year before, improving off a terrible base shouldn’t really be a cause for celebration. As of year-end, the company had incurred accumulated losses of $332.6M. Unsurprisingly, the auditor in the latest report has raised “substantial doubt about the Group’s ability to continue as a going concern”.

Scale and (in)efficiencies

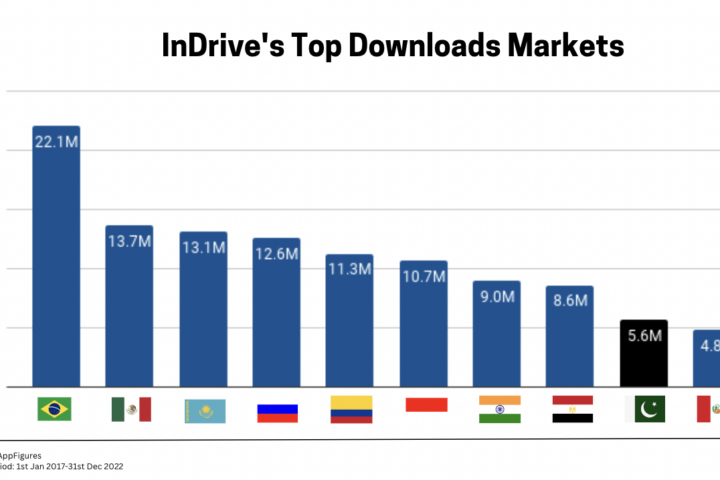

Before we peel more layers of financials, let’s first understand the revenue mix and some non-operating metrics. To start with, Swvl saw its total bookings (completed or canceled) reach 45.7M in 2022, from 25.9M the year before. That may seem impressive at first so context is important. Careem did 97M trips over the same period, which is actually well below their peak. In theory, a mass transit service should have far higher scale than a mature ride-hailing platform well past its time. But apparently not.

The higher volumes weren’t enough to fundamentally improve the underlying unit economics either. In fact, the gap between average ticket fare and cost per available seat turned negative and reached $0.08 in 2022. However, utilization improved to 96%, from 89%.

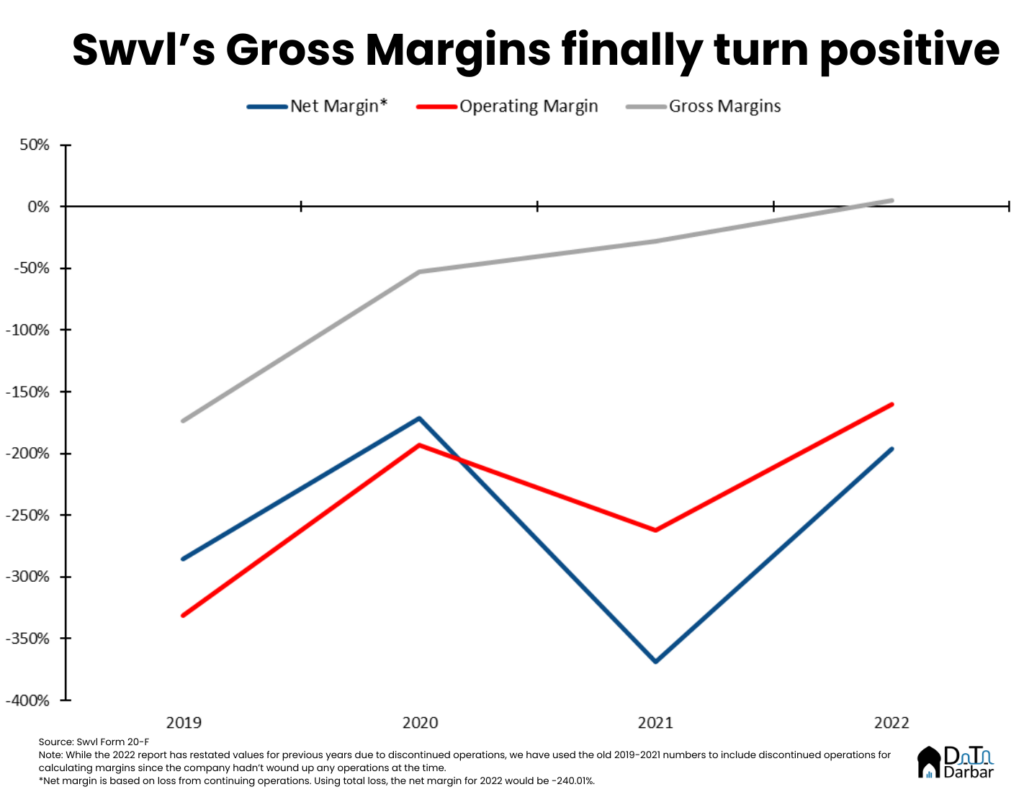

Meanwhile, in terms of core financial metrics, the picture looked more grim even as gross margin turned positive at 5.35% in 2022, from -22.63% the year before. Technically, the operating and net margins also “improved” to -160.01% and -196.07% but only because the base was unbelievably awful, at -344.66% and -504.97%, respectively. It kinda gets worse, as the net cash flow from operating activities worsened to -$117.46M, from -$62.13M in 2021.

A wild ride from growth to crash

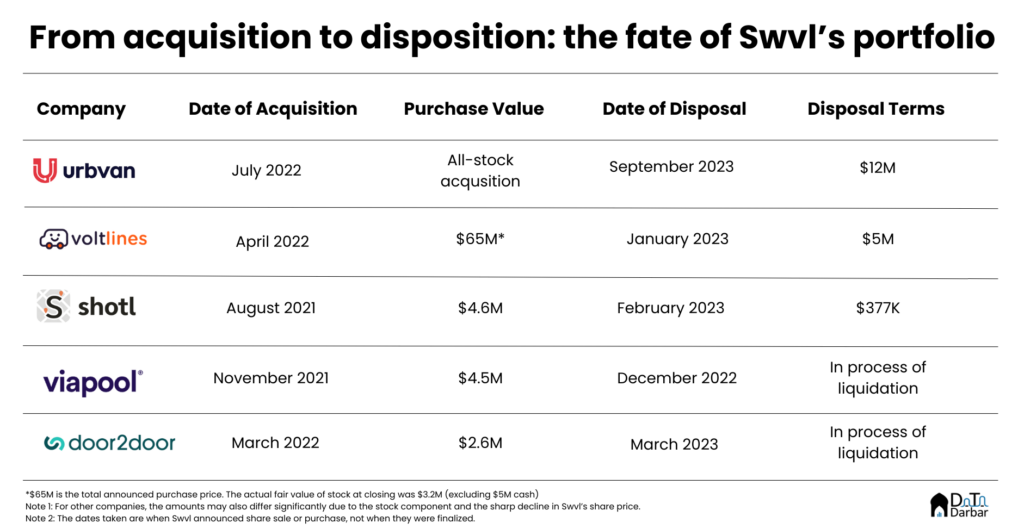

For Swvl, the last two years can be broadly broken into two parts. The first half was a period of excitement and growth, during which they not only debuted on NASDAQ but also went on a shopping spree. In August 2021, the group bought a 55% stake in Barcelona-based Shotl for $4.6M. Then in November, it entered into an agreement to purchase Viapool from Argentina, though the transaction was completed in 2022.

The speed only picked up afterwards as during the rest of the 2022, Swvl scooped up Door2Door from Germany, Volt Lines from Turkiye, and Urbvan from Mexico. It looked like there was nothing stopping the growth, both organic and inorganic, except of course the weakening financial position.

While the shopping spree continued, the group also announced its “portfolio optimization plan”. Basically the tech/finance bro speak for cost-cutting. They reduced the headcount by 32% and pulled back operations from multiple markets. For example, in June, Swvl announced shutting its B2C segment in Pakistan. This was part of the broader tilt towards B2B, whose share in total revenue from continuing operations surged to 73.59% during 2022, from 63.84%.

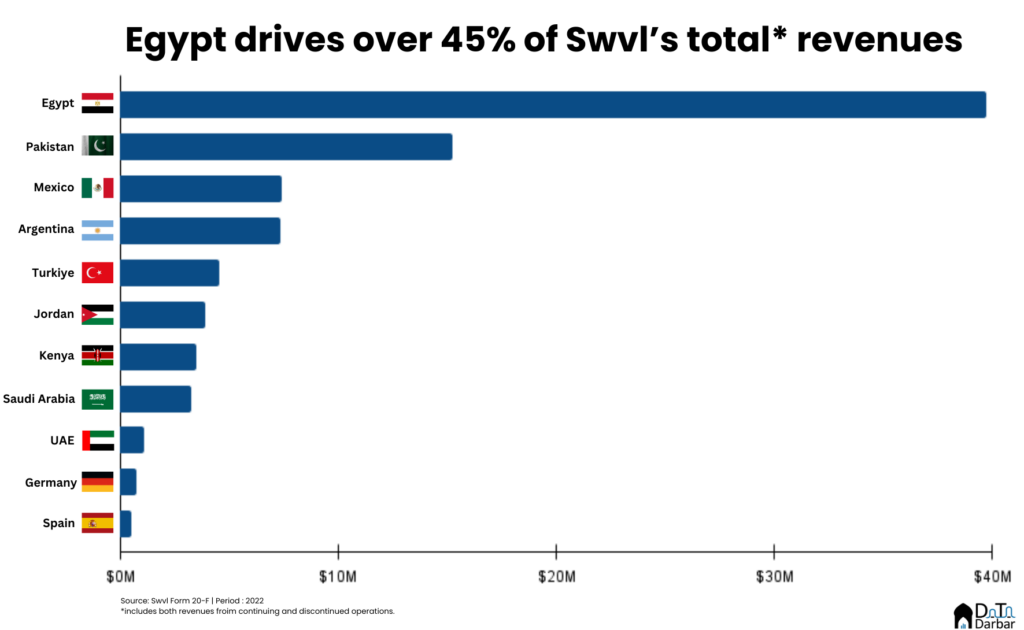

That optimization program had to be notched up further towards the end of year, when the group exited from markets like Pakistan, Kenya and Jordan. Combined, these countries had a revenue of $22.59M in 2022, or 25.89% of Swvl’s entire revenue (including discontinued operations). Interestingly, the three geographies accounted for just 13.09% of the overall operating loss.

Basically, they were bringing in relatively more dollars and at a pretty healthy growth too. For example, Pakistan’s revenue in 2022 had increased by 46.7% to $15.24M, second only to Egypt’s $39.7M. Even the operating margins of -57.62% were considerably better than the group’s -160.01%. In April 2023, it sold Swvl Pakistan for just $20,000 to Danish Elahi, a Karachi-based business magnate who has built quite some portfolio in logistics which includes the likes of BlueEx, Daewoo among others. Similarly, the operating margins for Kenya and Jordan were -47.88% and -88.71%, respectively. So the rationale behind the selection of those markets is not exactly clear.

Anyway, things began to unravel faster afterwards especially as pretty much all of the acquisitions fizzled out. Take Volt Lines, which Swvl had announced to buy for a (cash + stock) consideration of $65M in April 2022. But by January 2023, the target company was returned to its original shareholders.

In a press statement, Abdullah Mutawi from Dubai Angel Investors said: “Volt Lines has performed exceptionally well during a period when Swvl has faced some tremendous challenges. Ultimately, we felt that the various challenges Swvl was dealing with were hampering Ali’s ability to accelerate Volt Lines growth more aggressively which is why we collectively concluded that Volt Lines would be better served into the next phase back under the ownership of Ali and its original shareholders.”

Writing on the wall

This was a feature, not a blip. Since then, four more acquisition targets have been disposed of by the group, either through sales or ongoing liquidation. Like many startups, Swvl’s journey was exciting first and then tumultuous, but it was in no way unforeseen. As early as August 2021, there were multiple indications available on how the underlying model wasn’t exactly working out. Not to mention the attempts at sugarcoating financial metrics with the help of some accounting wizardry.

For instance, Swvl’s first public investor presentation mentions how its gross and net margins were at 20% and -8% by March 2021. That sounds impressive, right? But it doesn’t reconcile with the numbers stated above. So what’s the deal? And no, we are not conspiring to defame startups here, as much as those entrepreneurial WhatsApp groups try to suggest. The reason is simple: the company was reporting a non-IFRS measure. When it move to an international accounting standard, the bubble popped.

While Swvl’s journey has been both extreme and under limelight, it was far from the only one. Countless startups have tried to play the same game of unbridled growth bought by venture dollars, and then doing accounting maneuvering to show scale and bring in even more funding. The whole cycle is vicious which works really well until it doesn’t. Now that capital is in short supply, everyone’s talking sustainability, including those who laid the foundations of the old system. Rest assured, once the money returns, we’ll go back to the same pattern. Markets are bipolar like that.