With a million messaging platforms available at virtually no direct cost, many of us have forgotten what the olden days were like when you had to pay a couple of rupees for each text and fit everything into 140 characters. Back then, Telenor Pakistan disrupted this (and our communication habits) when its flanker brand, DJuice, lowered the price of SMS to just 24 paisas. Anecdotally speaking, it was a big hit, at least among the youth who keenly moved away from landlines. However, almost two decades later, that company is leaving the country after selling its stake to Ufone.

The rumors of Telenor’s exit had been circulating for a while, and in November last year, the company officially invited bids for Pakistan operations. If anything, the formal acknowledgement came a little too late as the cracks were a bit too obvious by then. Let’s start from the very basics.

Telenor’s Financial Troubles

For years, Telenor had been struggling to grow its revenues, let alone the line items beneath that. After hitting a peak of PKR 112.6B in 2018, the topline is yet to recover to that level again. The number stood at just PKR 109B in 2022 despite the PKR losing over half its value in six years.

In terms of dollars, the decline is obviously sharper, where the 2022 revenue of $558M is the worst since 2008. Compared to the peak of $984M in 2017, it’s down 43.3%. Of course, Telenor is far from alone here. Given the extent of the rupee’s devaluation over the last six years, there might be very few non-export companies in Pakistan that have grown in USD.

Lagging behind

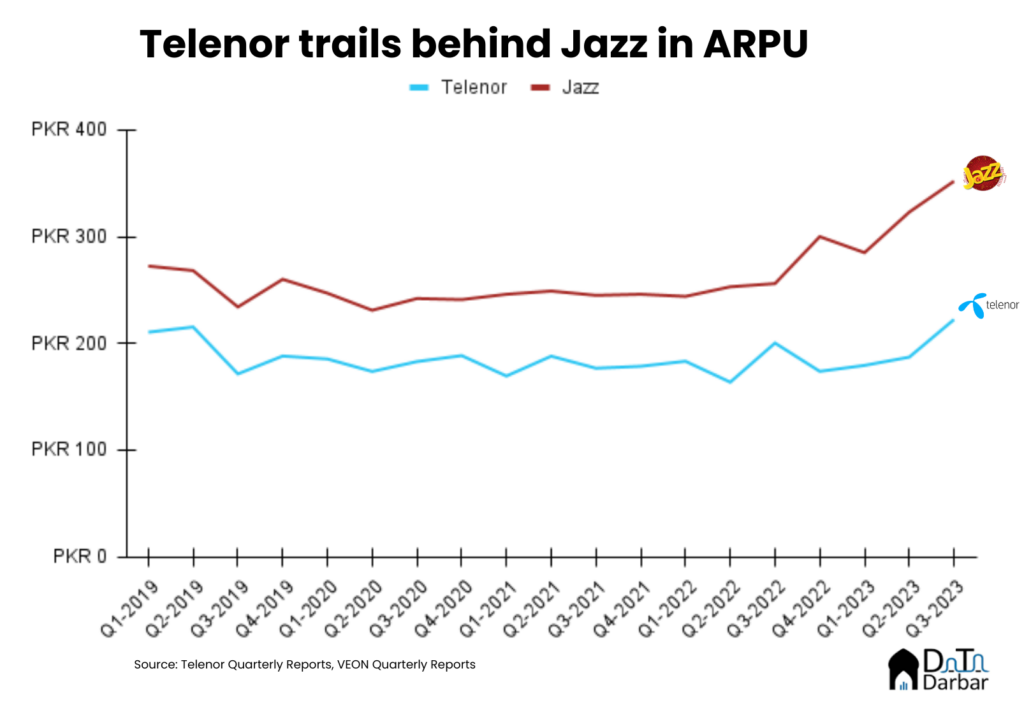

While the macroeconomy did certainly play a significant role in amplifying Telenor’s troubles, there were problems within as well. Or at the very least, we could say that certain strategies backfired. For example, the company’s push to increase subscribers dragged down the average revenue per user, which has stayed below PKR 200 in 15/19 quarters since 2019. Between Q2-2021 and Q3-2022 (the last period for which PTA published data), its ARPU consistently lagged behind the industry average. The position looks even weaker compared to Jazz’s PKR 352 in Q3-2023.

One reason behind the low ARPU was the company’s earlier push towards bringing relatively “low-value” customers, often rural. However, by mid 2023, former CEO Irfan Wahab Khan had moved away from this strategy, claiming that the number of subscribers was a “fake performance indicator”.

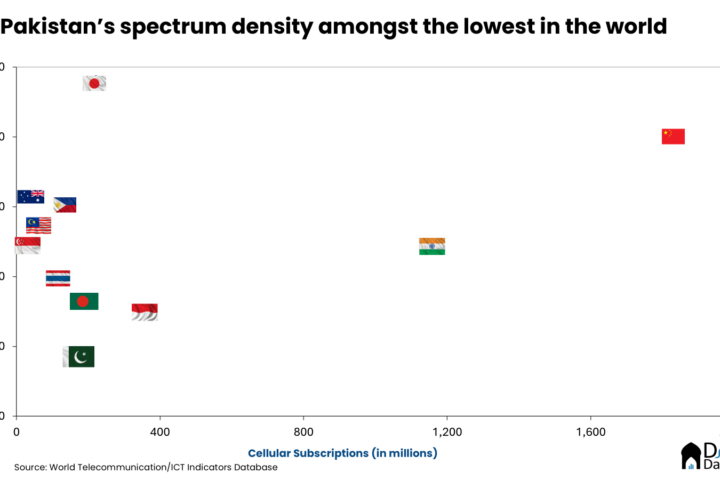

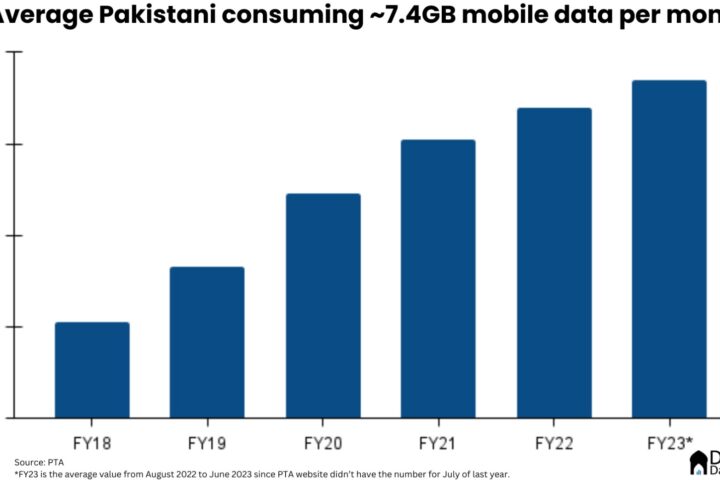

Basically, in the race for higher market shares, MNOs added tons of customers who didn’t bring in a lot of economic value. Most of them are trying to amend this by increasing the share of data in total revenue as that entails upselling opportunities and more stickiness. While Telenor doesn’t give a breakdown of its topline by voice or data, its broadband performance has been quite underwhelming.

According to Ookla, Telenor’s median download speed of 4.77 Mbps is the lowest among all service providers and almost a fifth of Jazz’s 20.63. Moreover, it also performed the worst on consistency, scoring 42.5% in Q3-2023. So, when it came to delivering quality, the telecom operator has been far from impressive.

Overall, the financial performance has continued to deteriorate, with operating profits to revenues receding from its peak of 36.7% in 2018. In 2022, the ratio was actually in red at -19.8% because of a $250M impairment loss in the second quarter. The company also recorded a net loss of $381M during the year.

This is in stark contrast to Jazz, which managed to increase its revenue by 27.1% YoY to PKR 81.5B during Q3-2023 in PKR terms. On the other hand, Telenor was up only 4.7% in the corresponding period. Understandably, the picture looked much different in USD, where the former declined by only 3.5% versus the latter’s 21.1% dip.

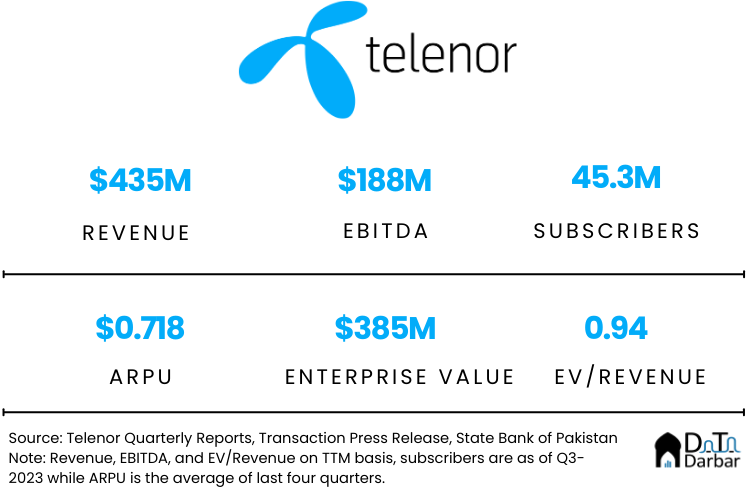

Putting the transaction value of Telenor in context

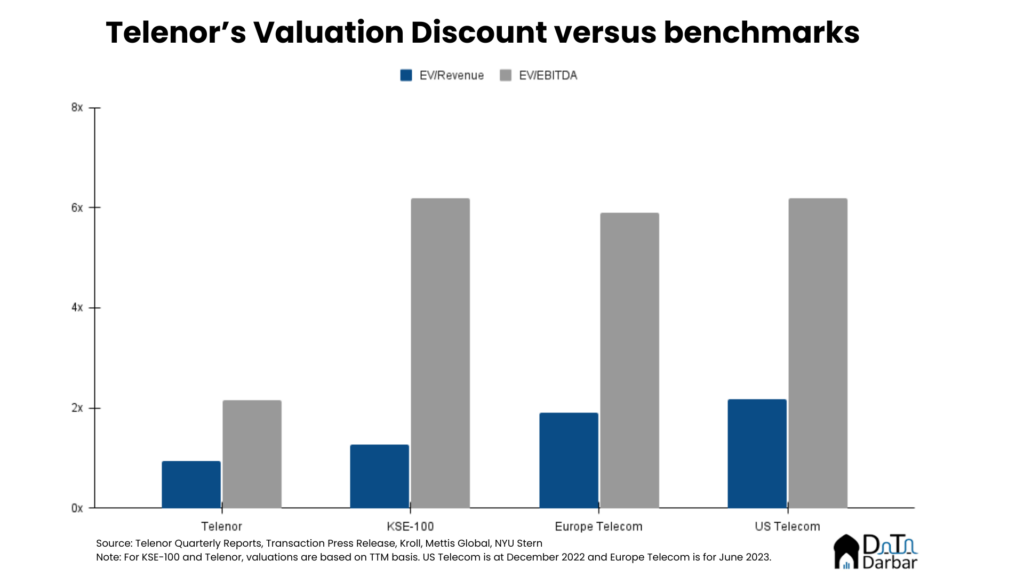

I guess that’s more than enough on why the Norwegian telecom was looking to divest from Pakistan. Now, let’s turn to the transaction itself. Last year, when Telenor invited bids, it was eyeing a price of $1B. Even earlier in August, media outlets reported a figure between $500M and $700M. The actual enterprise value turned out to be $385M, so the gulf between expectation and reality is substantial.

On a trailing twelve-month basis, it translates into EV/Revenue of just 0.94 and EV/EBITDA of 2.16. Compared to telecom services in Europe (as of Q2’23), Telenor was sold at respective discounts of 49% and 37%, according to data from Kroll. Meanwhile, the corresponding multiples for the US (Q4’22) were 2.18x and 6.18x.

Given Pakistan’s risk, the difference is understandable because of the underlying country risk . However, Telenor’s transaction represents a steep discount even compared to the local market. According to data from Mettis Global, the EV/Revenue and EV/EBITDA multiples for KSE-100 as at Dec 26th were 1.27x and 6.18x though the only telecom there is the acquirer itself, i.e. PTCL.

The Competition versus Efficiency Tradeoff

The merger has effectively reduced Pakistan’s telecom market players from four to three (ignoring Special Communication Organization — SCO) and increased Ufone’s share in mobile broadband to 33.09%, from just 12.43%. That means lower competition and is often associated with the loss of consumer welfare. To assess concentration in an industry, economists use the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index which basically is the sum of each firm’s market shares squared. A value under 100 indicates a highly competitive industry. Anything above 2,500 is believed to be highly concentrated.

HHI = (Market Share of Firm 1)² + (Market Share of Firm 2)² + … + (Market Share of Firm n)²

Using the overall cellular subscriber data from October, Pakistan’s HHI was already 2,741. Post-acquisition, this figure will go all the way up to 3,374. By FY23 mobile broadband shares, the HHI was higher at 2,787 and will increase to 3,325 after the merger. So purely from an antitrust perspective, this transaction should face serious scrutiny. But given that the Government of Pakistan owns PTCL, it shouldn’t really pose much problem. Plus, we aren’t really an exception as telecom around the world has high concentration. For example, in India, the HHI was 2,953 and is above 2,500 across the G7 countries.

Consolidation in telecom is attributed to the nature of the industry itself, where profit is highly contingent on economies of scale making up for the large investment costs necessitated by upgrading infrastructure. However, antitrust activists believe that higher concentration can be damaging for consumers, especially with respect to pricing and service quality.

Research in the EU found a 16.3% estimated average price increase in telecom markets where there has been a four-to-three merger. The same study found a 19.3% estimated average spike in the investment per operator due to the merger. We’ll find out which way Ufone swings in time, but for now, there's room for cautious optimism. For starters, e& is pumping marketing money into Onic, which is a positive sign. But the more important concern is whether the higher market share will incentivise telecom companies to make the heavy capital requirements needed to upgrade infrastructure.

Good insight.

Will telenor and ufone merge together

I think further market consolidation will affect consumer rights. However, I

t is expected that PTCL group may think about acquiring Nayatrl or other operators. Clearly the objective of e& is to become SMP and dictate market profitability and higher ARPU.

One of the best articles I’ve read recently. Hats off. We need more people like you driving our social media

Good analysis

Very good and detailed analysis

Good analysis reports I use telenor and jazz.

My favourite network ❣️❣️❣️

Good analysis 👍