Few sectors in Pakistan can claim the kind of growth that nano lending has had in the past two years, even as everything else seems to have crashed. The space started taking shape in June 2021 with the launch of Barwaqt on Google Play, now the biggest player. Since then, billions of rupees have been doled out across millions of instant loans.

And a lot has been written about it: how so many (often foreign) unregistered players are freely operating, how even the licensed entities are no less exploitative in nature with annual percentage rates running into four digits, and how the customers are being harassed. The brouhaha was enough for the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan to take action and introduce amendments to the Non-Banking Financial Companies Act.

Nano is the new micro

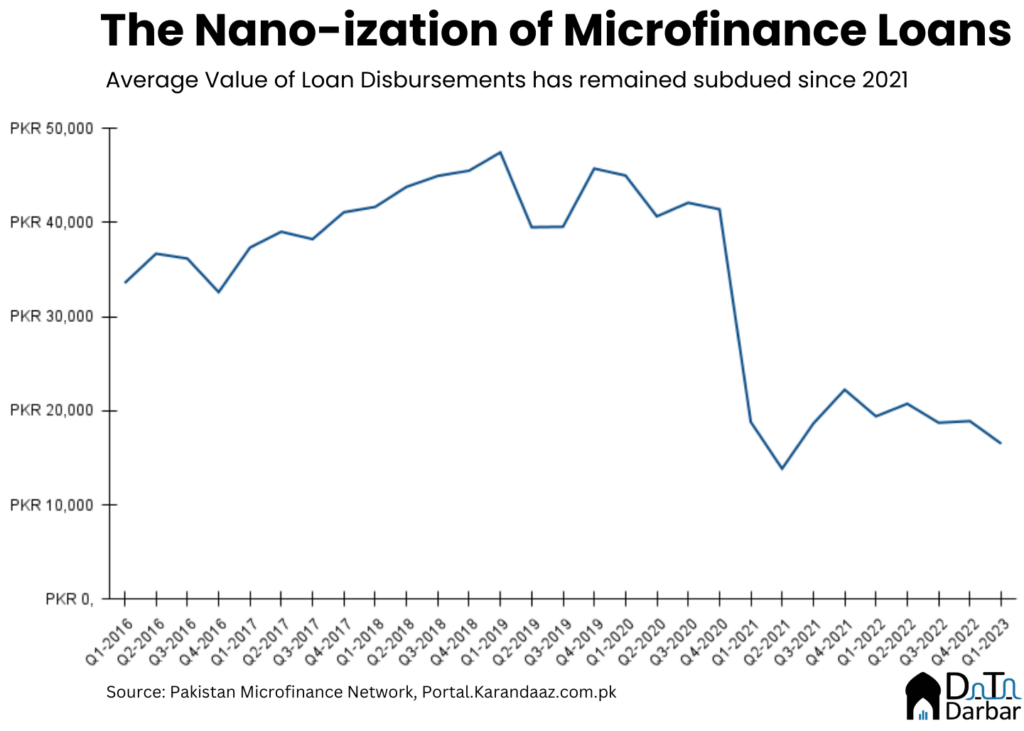

But the same shift towards nano is not only limited to the unregulated or the new digital NBFCs. It’s happening in the supposedly more regulated microfinance banking, for even longer. According to the Pakistan Microfinance Network, the average value of disbursed loans to individuals stood at PKR 16,524 in Q1-2023. This is lower by 12.7% QoQ and 14.9% YoY. But the real trend becomes visible when you stretch the period a little further.

It all seems to have started back in Q1-2021 when the average size of disbursed loans to individuals suddenly plunged to PKR 18,829, from PKR 41,398 in the preceding quarter. This is too sharp a decline and was a reversal of the generally upwards trend that had been in place since at least the beginning of 2016.

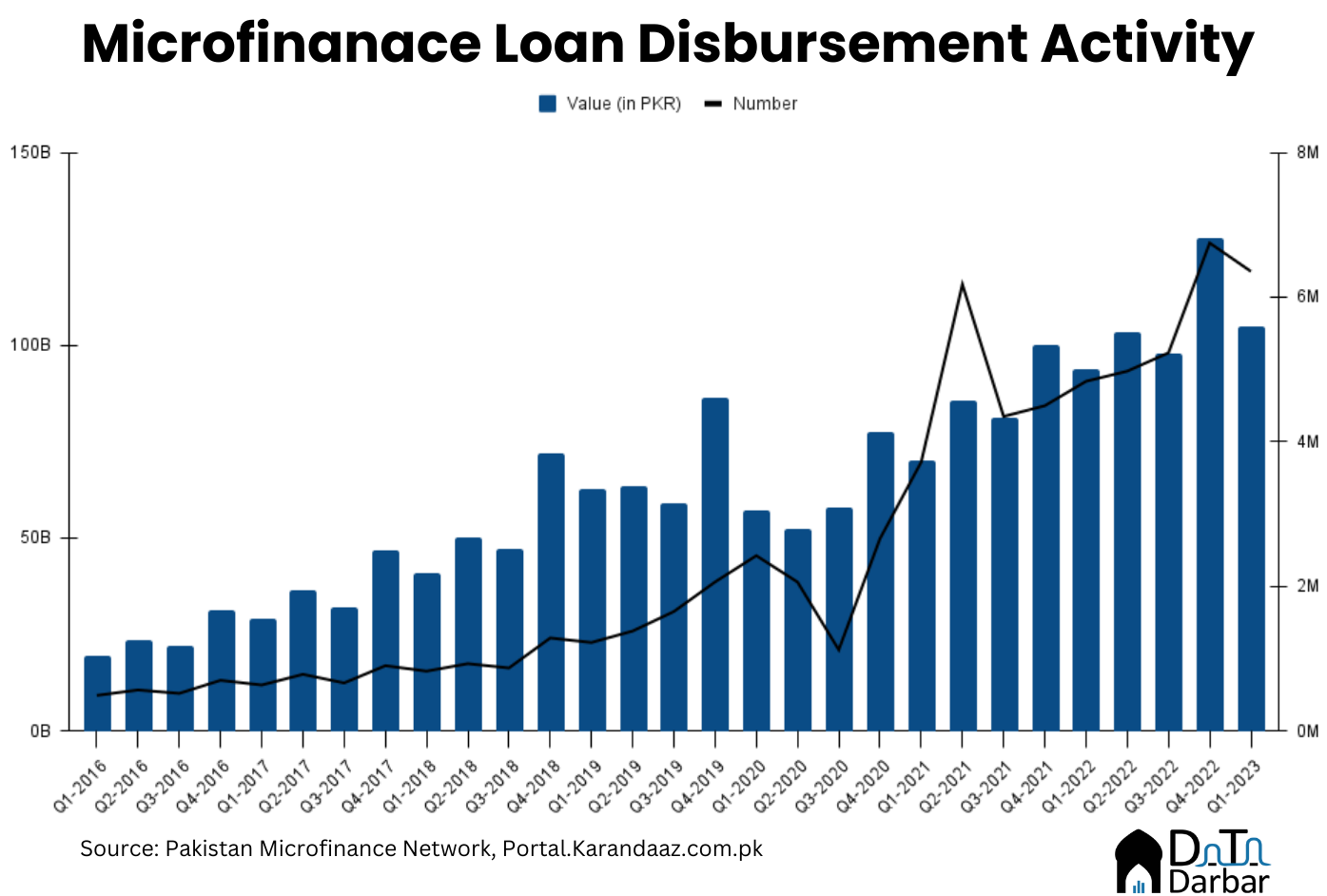

So, what happened? Well, the denominator shot through the roof. In Q2-2021, the number of disbursed loans to individuals increased by 2.46M to 6.18M, from 3.72M the preceding quarter. The same trend persisted the next quarter, with their respective YoY growth rates of 200% and 288%.

Meanwhile, the amount of disbursed loans to individuals stood at PKR 105B. This is a decline of 17.7% QoQ but an increase of 11.8% YoY. Between the March of 2016 and 2023, the value of disbursed loans to individuals has increased at a compound annual growth rate of 27.1% and the number at 44.2%.

Telco-backed wallets lead from the front

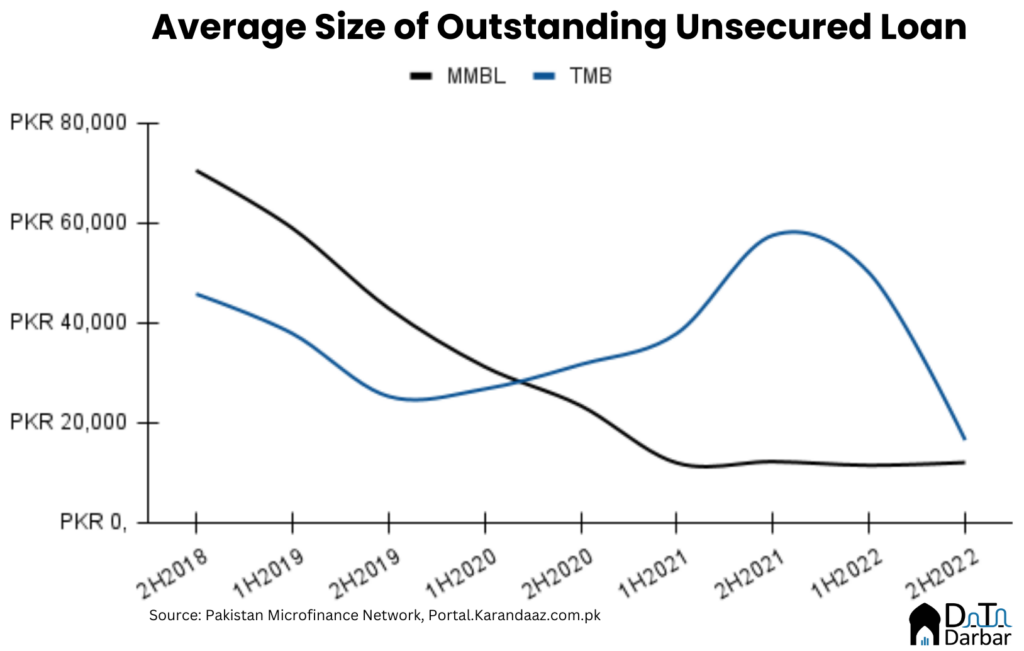

Understandably, the telco backed mobile wallets are at the forefront of this race to the bottom. After all, they have both the tech and the sponsors to disburse credit to millions at speed. We looked at their the amount and number of outstanding unsecured loans since 2018 as a proxy. [Yes, not all of it would nano but there is a strong correlation.]

For example, Mobilink Microfinance Bank, the largest player in the industry by active borrowers, increased unsecured loans to 2.57 million in Q1-2023. At the end of 2020, this numbert stood at 709.6K. As a result, the average outstanding loan has declined from PKR 23,249 to PKR 12,057 during the period under review.

By 2022, MMBL had outstanding nano loans of PKR 4.7B, or 8% of its gross portfolio of PKR 58.9B. This translates into 2.3M active borrowers from whom it recorded Rs5.9B as markup income. This continued in 1Q-2023, when the interest from nano lending was PKR 2.47B or 42.3% of total markup from advances. It represents a growth of 243.9% YoY in absolute value and an increase of 11.4 percentage points in share. At this rate, the bank should be an exclusively nano player sometime next year.

On the other hand, Telenor Microfinance Bank has seen a somewhat bumpy ride. It started nano in 2018 but the overall lending portfolio unravelled and had to book a credit impairment charge of PKR 8.87B in 2019. For the next couple years, the management invested in restructured and then returned to nano loans only sometime in 2022.

According to the Microwatch data, the microfinance bank registered the highest increase in active borrowers across industry for two quarters straight. In Q4-2022, the number jumped by ~215K and then by another ~182K during Jan-Mar.

Similarly, TMB’s count of unsecured outstanding advances surged 418% to ~634K in Q1-2023, from ~122K in the same period last year. In comparison, the amount rose by a modest 13% to PKR 8.27B. Resultantly, the average outstanding value fell to just PKR 13,047, from PKR 59,802 in the corresponding quarter of 2022. With respect to nano credit specifically (instead of unsecured outstanding values), the annual annual report notes it disbursed 1.5M loans worth PKR 4B. So an average of just PKR 2,667.

Why does it even matter?

When it comes to access to financing, Pakistan performs fairly poorly with private sector credit at only 15.4% of the GDP. Most of that also goes towards big corporates, leaving little for small businesses and individuals. Banks just don’t lend to these segments so they turn to microfinance institutions and informal markets.

Microfinance sector, in particular, has long boasted about its role in increasing access to credit. As of Q1-2023, it had a gross loan portfolio of ~PKR 510B across ~9.3M active borrowers. And these are traditionally unserved or underserved segments who wouldn’t otherwise be entertained by banks. However, due to the risk involved, the interest rates are higher and stood at 38.4% for gross disbursements in March.

For many, this is already too high. But the industry argues that these borrowers wouldn’t have been able to borrow otherwise. Or worse, turn to loan sharks who charge annual markups of hundreds of percentage points. So basically, microfinance has allowed them to access money for starting new businesses, healthcare expenses, weddings etc.

With nano loans, those noble claims of financial inclusion begin to feel quite hollow. Firstly, the amounts in question are literal peanuts (not even a kilogram of them) and can’t possibly help with productive or important use cases. Secondly, the interest rates are substantially higher and are pretty much on par with the infamous loan sharks.

I don’t know about others but markups of ~250% is textbook usury to me. That too by well-respected institutions and self-proclaimed flag bearers of financial inclusion. Of course, the industry has tried to spin it around with all sorts of reasonings. Like two years ago, MMBL CEO argued how the traditionally used APR is a wrong metric due to small ticket sizes.

Nano is riskier by nature because it’s instant. There’s no on-ground staff to recover money borrowers so to compensate, a higher markup is required. Finance 101 is clear on that, no doubt. But if you are going to charge extortionary interest rates that help create debt traps, at least don’t call it financial inclusion.

A shorter version of this piece originally appeared in Dawn.