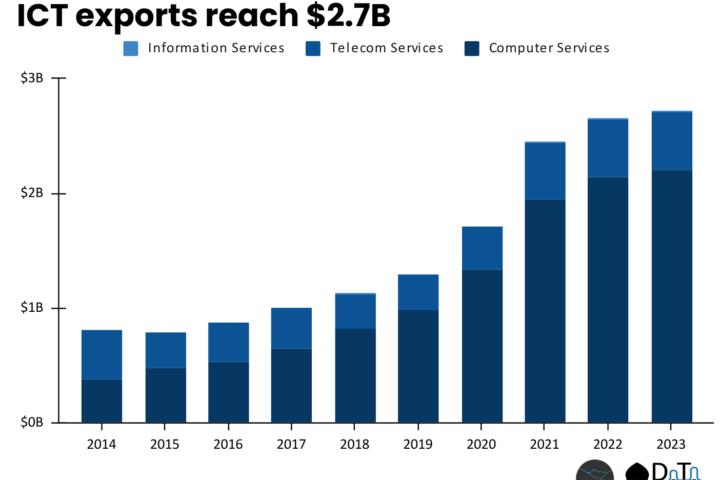

For almost a decade, Pakistan’s software industry and the relevant ministry have been throwing around lofty targets for IT exports. Depending on where you lie on the ambition scale, the number can vary between $5B and $20B. The reality, however, has been starkly different, and disappointing, with our current proceeds at ~$2.5B.

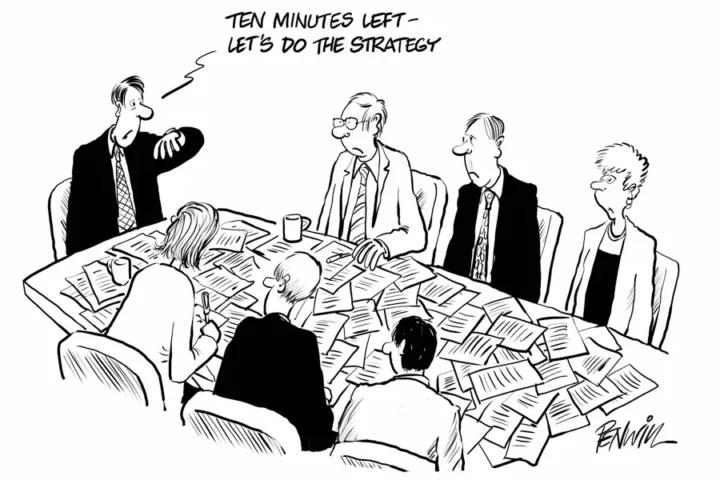

While last year’s economic and political uncertainty surely hit IT sector exports hard — at least what they brought back to Pakistan — there was no way the targets would have been achieved even if everything was hunky dory. Reaching those lofty goals of $5-20B requires much more than giving hollow statements to the press.

There’s no denying Pakistan’s export potential in information technology. This is a country of young, tech-savvy people up for grabs at cheap rates. It’s basically a labor arbitrage play. But do we really have the human capital available to reach those numbers? According to the Labour Force Survey 2017-18, ~340K people were part of the sector. Since then, the industry has witnessed a steep uptick and according to Data Darbar’s projections should have a workforce of at least ~600K even at a relatively conservative growth rate of 12% per annum.

Basically, to grow our tech sector exports by 5-10x, we need to build the human capital pipeline by the same factor. As it stands, the country only adds 25-30K new IT graduates every year to the market. Meanwhile, the IT sector adds ~2,500 companies annually, which means the current supply of talent won’t be able to meet the demand.

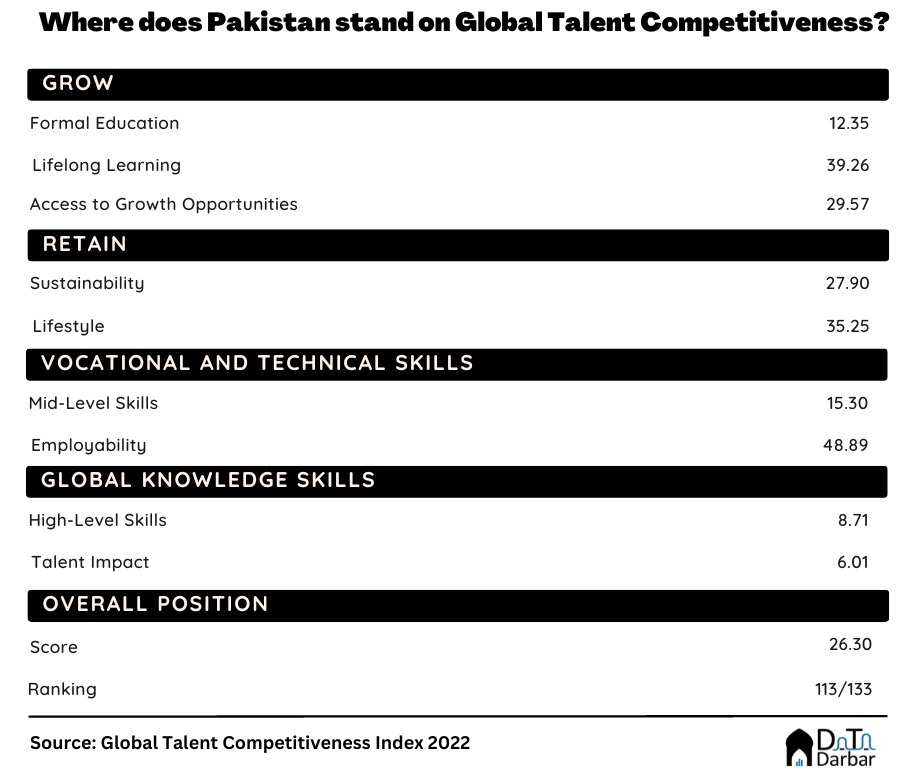

Not just the quantity, but there are also issues with quality as well. Industry leaders like Asif Peer have time and again talked about how only 20% of all graduates are employable. A number of global indices attest to this fact too. For example, Pakistan ranked 113 out of 133 countries on Insead’s Global Talent Competitiveness Index in 2022.

Factors Hindering Talent Competitiveness in IT Sector

But why exactly is Pakistan’s talent competitiveness so low? On the supply side, the current education infrastructure is a bottleneck to the country achieving better technical graduate numbers. Enough universities aren’t there to fulfill the demand for such degrees. And whatever few exist, their quality is usually so low that the graduates are deemed ‘unemployable’. According to the QS rankings for Computer Science, only 5 Pakistani universities make it to the top 400 in the world, compared to India’s 14.

The Indian Institute of Technology, associated with the rise of the IT industry in India, dominates the subcontinent in these rankings, with 4 of its universities making it to the top 100 and a 5th ranked 101. Meanwhile, Pakistan scores 30.8 out of 100 on GTCI’s university rankings metric.

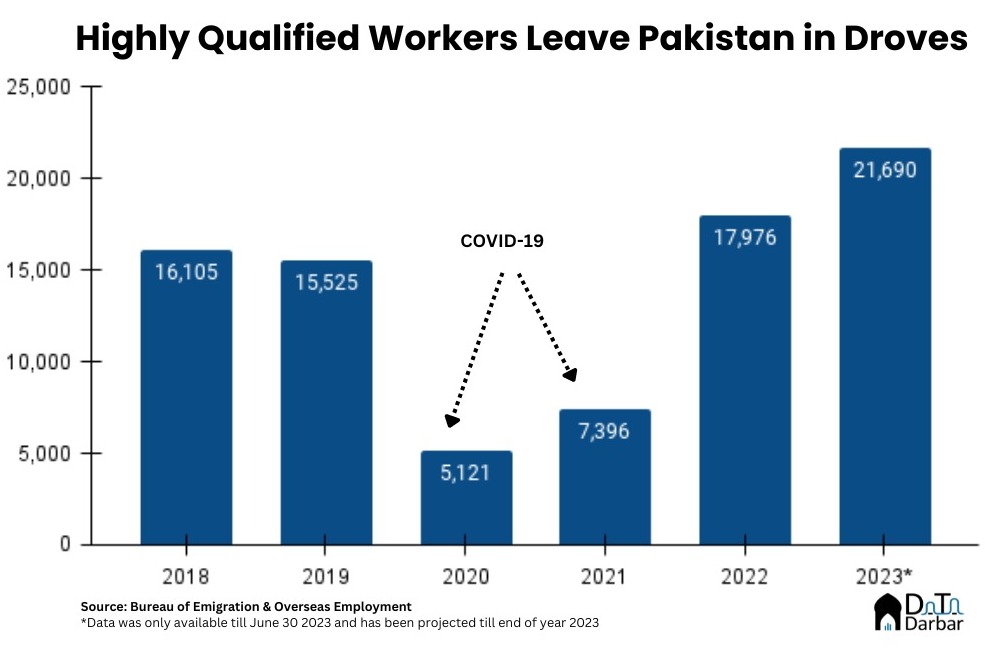

Then, there is the case of brain drain. The latest numbers show an increase in the highly-skilled workers leaving the country. The country’s instability, as well as the low compensation for technical workers in the country, make moving abroad a better option for these workers where their skills will be utilized as well as fairly rewarded. The GTCI also confirms this, with Pakistan’s score of 31.57 out of 100 on the ‘Retain’ indicator — a damning indictment of the ability of Pakistan to keep its brightest talent.

The index confirms much of what we already know. Pakistan lacks the skilled talent needed for it to meet its IT export targets. But then why do we score 58.83 out of 100 on Highly Educated Unemployment, indicating that many of our university graduates actually find it hard to get jobs? This may be because of a market asymmetry, whereby the degrees that the highly educated ones get happen to be the ones for which there is minimal demand.

Overcoming Infrastructural Constraints in the IT sector

For instance, there were 581,445 students enrolled in programs relating to engineering, the natural sciences, and mathematics across the country in 2020-21. Many of them should have graduated by now and could either be unemployed or underemployed (working in non-technical roles). This is because Pakistan’s largely uncompetitive manufacturing and research sectors have no room to employ them.

The easiest way to fix the talent problem would then be to retrain these highly-educated STEM graduates. This is also how the private sector is looking to build its talent pipeline. For example, Systems Ltd launched an IT Mustakbil Program last year. It inducts non-CS freshers and provides them with on-job training for a fast-track learning of the requisite skills to make it in the industry.

Asif Peer, the CEO of Systems Ltd, talked about the same thing in an interview a few months back. “We saw that computer science people are not going to be enough if you are to grow sustainably since there are only a few universities producing good graduates. Now with changes in technology, you don’t really need a four-year program if you have good IQ, critical thinking, and analytical capabilities. If you can train them on specific skill sets — such as no and low code, configurations, and e-commerce — it doesn’t take them two years.”

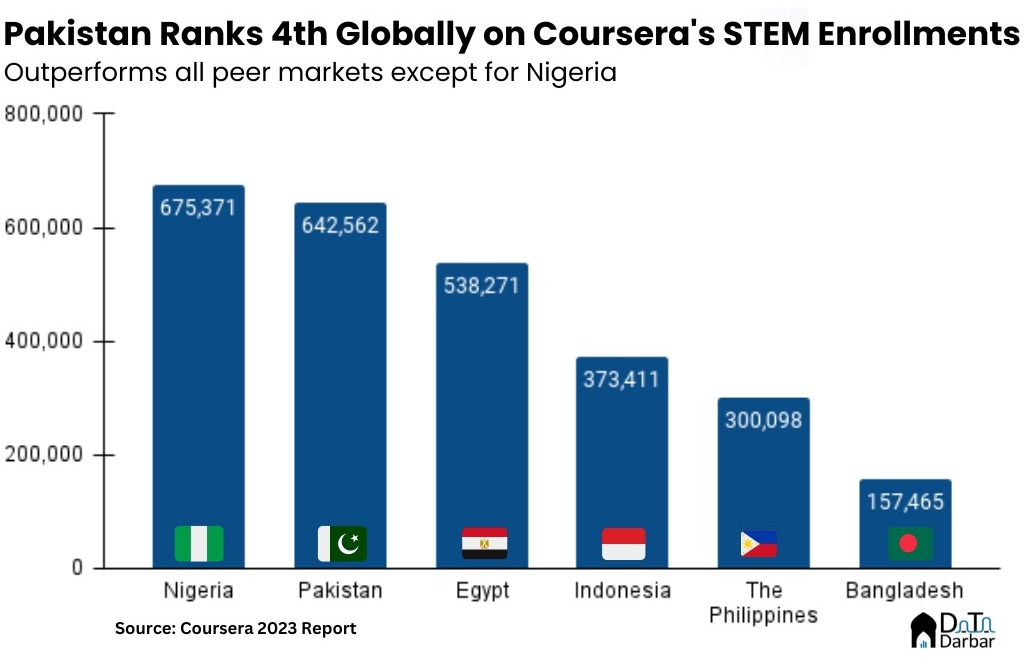

However, such institutional upskilling efforts have been few and far between so far, leaving everything to individuals. We sifted through Coursera’s 2023 Report and made an interesting observation. 642,562 enrolments in STEM courses came from Pakistan. This was the fourth-highest number of enrolments in the world, much higher than our regional comparables. Structural deficits aside, the resourceful Pakistani workforce has taken to online courses in an effort to upskill itself. The resource-constrained public sector has also stepped into the world of online courses, recognizing the potential to reach more people. One such example is Digiskills, a state-funded national training program. Digiskills claims to have imparted 3.5 million trainings since 2018, offering courses in Data Analytics, AutoCAD, and Digital Literacy.

The Future

It’s a double-edged sword. While there’s no doubt about the value of such courses, this is increasingly becoming a quick fix. Even an obsession of sorts. You can see countless merchants selling their snake oil-like short courses across a range of areas, from Amazon dropshipping to the ChatGPT grifters. And with the dearth of infrastructural capacity, can you even blame the people that buy into them?

But harnessing our IT export potential would require a more concentrated effort from all stakeholders. While quick vocational training is playing an important role in filling the gaping hole left by our education system, it is just a short-term fix, and ought not to be considered a substitute for institutional reform. Any scalable (and sustainable) solution will require institutional changes that the state and private market must work together to enact in order for Pakistan to firmly establish itself in the global IT market.

Good job!

so well researched, amazing work

Well written Shazaib. Get in touch for potential opportunities for yourself. LinkedIn: Suleman Ansar Khan

Its a great analysis must congratulate Shazeb for this contribution to this important field

Great observation!