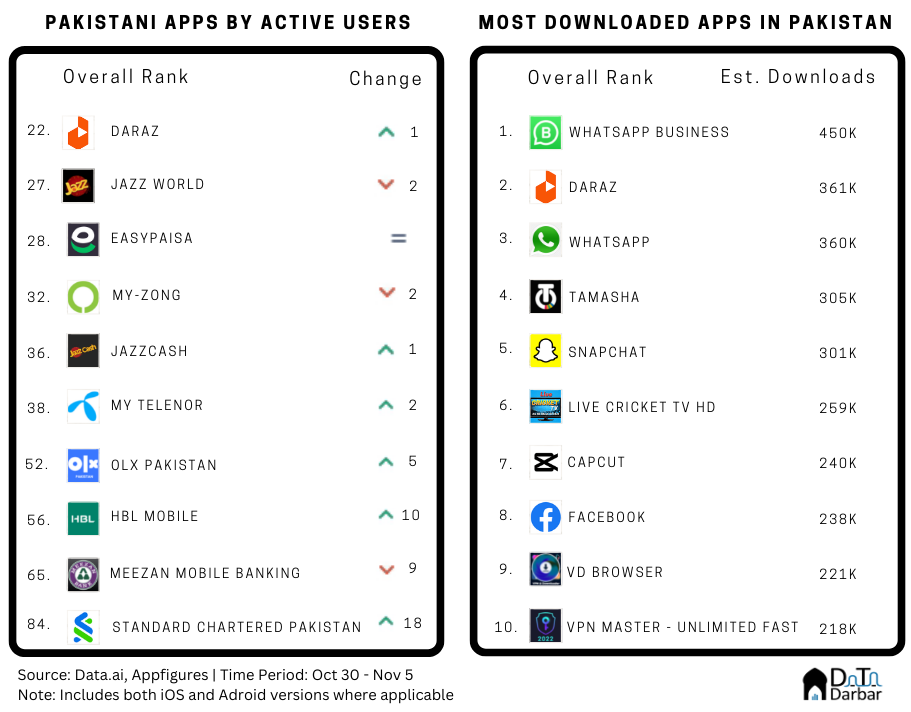

Welcome to the seventh edition of Appistan! Last week, we highlighted how the cricket effect was weighing on Pakistanis’ app usage, a trend only amplified between Oct 30 and Nov 5. As a result, Daraz rose to reach the top spot among local players on Data.ai’s Active User Rank, at 22nd place. This saw Jazz World finally sliding to second position. Overall, 13 apps made it to the Top 100, with Standard Chartered breaking in the first time since we started tracking. In terms of downloads, WhatsApp Business continued its dominance on the top spot with Daraz coming in second place. This was again thanks to the T20 World Cup, as three out of 10 apps were streaming cricket, including Tamasha. For the deep dive, we looked at Pakistan’s audio streaming landscape, its history, the recent growth trajectory among other things.

From USSD to Apps: how our music habits changed

In the age of Nokia feature phones, you’d get ringtones of your favorite songs by sending a code for Rs8. As curious kids who’d just gotten hands on their parents’ new mobile, us siblings started trying random sequences of numbers. It was a blind bet, made even riskier by the fact that when our mother finds out her Rs600 card (this is before the Rs10 easy load and Asma from hospital) has been exhausted, it will mean the end of us having access to the phone again.

Eventually, we did get some Bollywood bangers from the era but our access to the phone was denied for sometime. Kinda worth it, though. Soon after, Sony Ericsson launched its models which were known for audio quality. Better internal memory options and storage cards further made it possible for people to build their music libraries on their phones. It was still a task as you had to either download the songs from apniisp.com, transfer from computer or ask someone to send them to you via Bluetooth or Infrared.

Then came the early days of various app stores, wherein indie developers put up applications for songs, like milli naghmay or those of a particular artist. However, a majority of our population jumped all those phases and simply leapfrogged to (both foreign and Pakistani) audio streaming platforms. Now you can simply download an app and get access to a vast range of music libraries and playlists.

From being a mere value added service with meager contribution to revenue (if at all), music has now become big business. The biggest players like Spotify (and Youtube) have built a massive, and direct, global audience which no record company could previously imagine.

The Evolution of Pakistani Audio Streaming Scene

However, Pakistan has its own rich history of music – both mainstream and indie – which was basically a greenfield. YouTube did have a sizable collection but it was blocked in the country for years and wasn’t anyway a mobile-first audio platform. If you wanted to listen to lesser known gems, the best was to visit Rainbow Center and get a CD.

Then in April 2015, an app by the name of Taazi, founded by the pop icon Haroon, appeared on Google Play. In September, Patari came onto the scene with the promise of solving the supply side as well – i.e. paying artists. The startup saw its fair share of drama, with both ups and downs. Eventually, it became irrelevant from once being a major player, at least in the Pakistani Twitterverse.

In terms of numbers though, neither Taazi nor Patari were really up there even in early 2018. Among the Pakistani audio streaming platforms, it was actually bestsongs.pk. Launched in April 2017, it accumulated over a million installs in less than 12 months. Something the other two still haven’t managed to do combined.

What made bestsongs.pk different (and perhaps more successful) was its mix of Pakistani and Bollywood music. After all, the latter occupies a huge place in our music, and time, consumption. So any app that brought the two together would intuitively be more appealing to users.

The Bollywood Factor

This was also how a few Indian players continued to get meaningful traction from Pakistani users. In fact, the likes of Gaana and JioSaavn, at various points, tried to enter the market – the former partnering with carrier billing platform Simpaisa for payments and the latter even putting up billboards on the stress of Karachi. Hungama Music was also popular early on before it became unavailable locally.

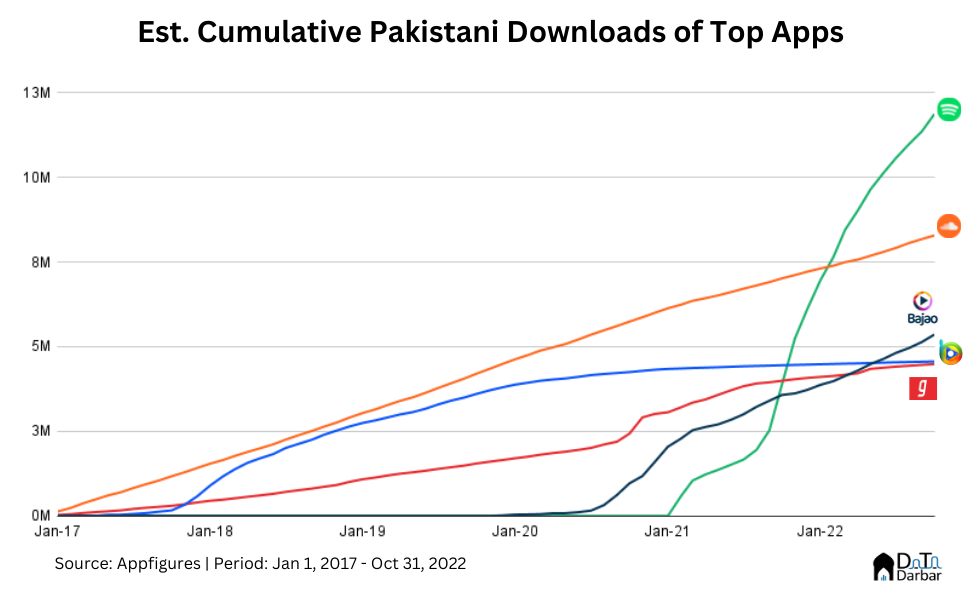

Due to the geopolitical tensions, their expansion plans fizzled out, at least formally. But the massive demand for Indian music here meant users never really stopped downloading those apps, who also have a decent Pakistani collection. That said, downloads of Indian apps have lately dwindled. While their share in our overall installs (between Jan’17 and Oct’22) still stands at 16%, it was just 3.5% in the last month. Most of this comes from Gaana, which has almost 4.5M installs (64K a month on average) during the period under review. The other two are far behind and have negligible numbers, especially of late.

Enter Spotify into the Pakistan Audio Streaming Market

Though geopolitics could be one explanation for Indian apps’ decline in Pakistan, the bigger reason seems to be Spotify. Since its entry, the global giant has swept away the market, as the steep growth trajectory below shows. In less than two years of launching, it’s now the single most downloaded app in the category, at around 11.9M.

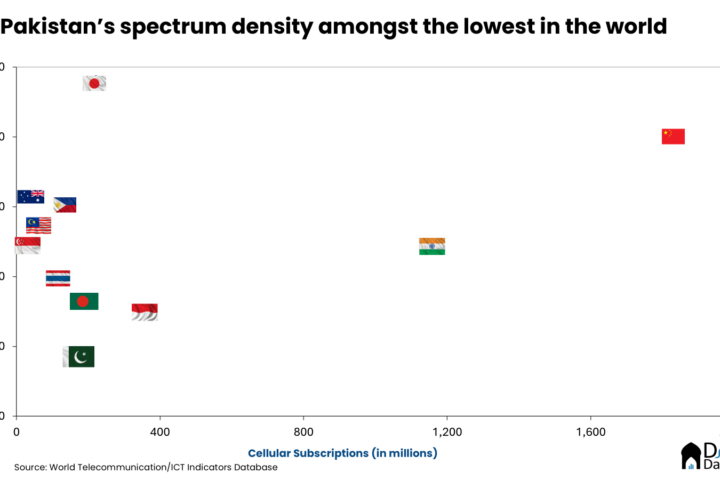

That shouldn’t be too surprising given how many Pakistanis were already using APKs to access Spotify. But its success in penetrating the mass market is still impressive. For starters, they had the budgets to put up billboards and sponsor cricket matches, on top of aggressive digital marketing. More importantly, their pricing was very much localized – unlike Netflix, Amazon Prime and the likes. Generally the problem in any subscription model is that very few people have credit cards in the country (barely a million). This is what Tapmad faced when it started out, eventually paving the way for the carrier billing platform, Simpaisa.

Since then, the same playbook has been adopted by other players like Tamasha, perhaps even more effectively. Spotify has been no different in this regard and offers flexible plans starting from Rs14 a week with carrier billing as a payment option. For the monthly and yearly packages, it has the usual card-based channels. Consequently, it caters to a wide range of audiences – something that many of the Pakistani audio streaming platforms couldn’t do. For example, Patari took five years to start monetizing through platform and by then, it was a little too late.

Beyond the mainstream

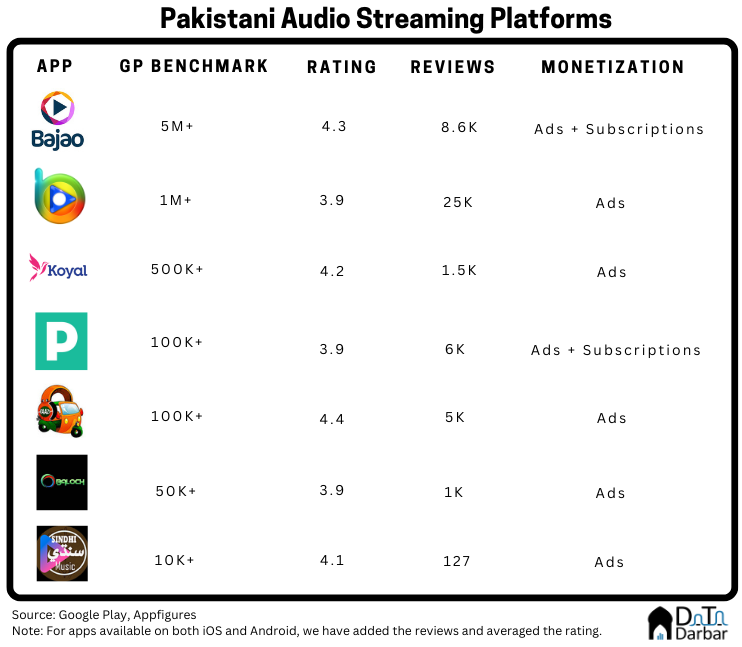

For most of 2019, bestsongs.pk was the sole local player carrying the Pakistani audio streaming scene on its shoulders. It saw around 1.15M installs during the year – doing more in a month than Patari and Taazi had in total. There was virtually no competition from within and little beyond either, as Indian platforms were always cautious. Until Jazz entered with Bajao in October 2019. Since then, it has been downloaded almost 5.4M times in the country, making it the third most popular platform.

More recently, it has been in second place, trailing behind Spotify. A cursory look at their collection shows the usual suspects: Bollywood hits, Atif Aslam, Sajjad Ali etc. But beyond that, the app has tried to tap on the market for regional music, from Pashto to Sindhi songs. Telenor has also adopted a similar strategy for its Koyal Music – an exclusively regional music platform. Its numbers pale in comparison though.

However, long before telcos entered this scene, it was three computer science grads from Quetta who tried to do it. In February 2019, Thaheer was published on the Play Store with the hope of bringing Balochi music online. They managed to bring around 150 local artists onto their platform and tried the subscription route as well. But David was apparently no match for Goliath, as the application is no longer available. Yet, the smaller players have continued their efforts to promote their culture and give the indie musicians a voice. OBaloch and Sindhi Songs are currently carrying this baton. On the more South Asian classical side, Saarey Music hs tried to fill this gap. Headquartered out of London but led a Pakistani-origin CEO, it has also built some audience. As much as a niche platform can do, anyway.

As has become the norm among streaming platforms generally, both Spotify and Bajao are trying their hand at originals. Like Patari did before them. After all, you can milk Vital Signs, Junoon and Coke Studio only so much. Luckily, the music scene has evolved lately with the entry of new artists like Shae Gill, Hasan Raheem etc, which the overwhelmingly generation better relates to. However, as a boomer (at least mentally), I still find myself turning to the same old curated playlists on Youtube.